Professor Halleh Ghorashi reflects on the conditions that make sustainable change possible and her time as a revolutionary in Iran. She writes: “It did not take more than two years for the hope and solidarity during the time of the revolution to be replaced by hatred and violence. This experience showed me the dual face of the revolution, which I have often described as an experience of paradise and hell in a very short period of time.” Like people before her, Ghorashi urges people to have the patience to make long-term, sustainable changes. She leaves us with the question of how we can connect big ideals with small acts.

Connecting beyond borders and conditions for change

By Halleh Ghorashi, PhD

It was February of 2011 when I went to South Africa for the first time. I was invited for an academic conference in Durban. Two public events were organized as part of the conference, and I was asked to participate in the panel of one. In South Africa, I felt like I was breathing the air of a country with an extraordinary past. I was inspired and impressed to see how a county with such a harsh history of exclusion had been able to become an example of reconciliation and forgiveness. Being in South Africa connected me to the core issue which has been an essential part of my identity: creating conditions for durable change for a better society.

In spite of my enthusiasm, I was somewhat uneasy to talk to a completely unknown public. Being a regular public speaker in the Netherlands I know how important it is to have some understanding of the public when addressing an issue through a lecture. I always say that I am very sensitive to the public I talk to, sometimes even a bit too sensitive. So whenever I get compliments for my lectures, I give the compliment back to the public. As you can imagine this is quite difficult to do when the lecture does not go that well! Nevertheless, I find it essential to make a connection with the public I talk to; an unfamiliar audience makes me quite nervous.

Revolution Then and Now

“We believed that change needed to happen quickly and be as drastic as possible in order to destroy the old structures and replace them with new ones. In the end, the spirit of the revolution marginalized all the patient and peace loving people completely. Revenge and violence took over and overshadowed any possibilities for durable and thoughtful ideas of change.”

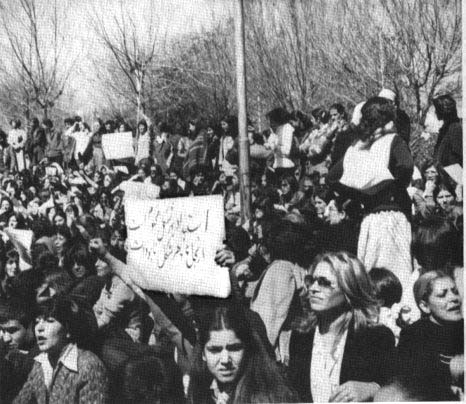

In addition, the timing of the event in Durban played a role in my doubts while planning my talk. The conference coincided with the protests in Tahrir square in Egypt. Like many others, I was glued to the TV to see what would happen next. Those scenes and discussions, the sense of solidarity and hope, and the incidental scenes of violence reminded me of my experience during the Iranian revolution of 1979. It reminded me of the great hope we had for the future of Iran. For me, as a 17 year old girl, being part of a revolution was like a dream come true. The fact that I could call myself a revolutionary gave me power. But most enriching was the possibility of reading books that had been forbidden and participating in lectures on different societal issues. Soon I became a very active follower of a Marxist-Leninist partisan organization. I soon became the student leader of my high school and a fanatical activist. It was amazing to feel the positive energy of idealism and the hope for change.

However, I (and many like me) soon faced the other (less positive) side of this revolutionary spirit as well. I remember the dominance of hatred towards the previous regime which fueled the urge for violent revenge. Looking back, I feel ashamed of the joy I felt when I saw the dead (and most probably tortured) bodies of old ministers in the newspapers. Rapid change was our goal at that time and the means would certainly justify the aims. I also remember how angry we became when any of the leaders at that time asked for patience. We believed that change needed to happen quickly and be as drastic as possible in order to destroy the old structures and replace them with new ones. In the end, the spirit of the revolution marginalized all the patient and peace loving people completely. Revenge and violence took over and overshadowed any possibilities for durable and thoughtful ideas of change. The result was that the systems changed from monarchy to the Islamic republic but the foundations of the old system (dictatorship, suppressive secret service, corrupt officials, and self-centered leaders) remained intact. This meant that from the start the revolution began killing its supporters and most tragically burying its ideals of justice and freedom. It did not take more than two years for the hope and solidarity during the time of the revolution to be replaced by hatred and violence. This experience showed me the dual face of the revolution, which I have often described as an experience of paradise and hell in a very short period of time.

How Can We Be Free?

With this short trip to my past, I hope I made clear what I meant by my emotional response to what was happening in Egypt. Watching those moments on TV left me with mixed feelings of hope for positive change and fear that the hastiness would not bring about inclusive change. Yet, those feelings were not only the result of my personal experience of the past but also my academic background during the past 25 years living in exile. When I fled to the Netherlands in 1988, I studied anthropology, philosophy, women studies, and organization studies, with the core subject of understanding the patterns of change and continuity in relation to individual, organizational, and societal sources of emancipation. How do individuals or societies emancipate or free themselves from the patterns of visible and invisible suppression that dominate them? How do we as individuals make sure that we are as free (by being reflective about our structural positioning) in our choices as we claim to be? How can our societies be(come) vital by enabling and facilitating free spaces to stimulate narratives from positions of difference which go against the justified normalized processes of exclusion? In short: how can we stimulate the conditions of possibility within the structures of impossibility?

Meanwhile, Back in Durban…

“The stories of the generations showed them [Black feminists] how the route of strength and pride is possible even in the most suppressive situations such as slavery and legalized racism.”

An hour before heading for the public lecture on categorization and otherness, I still did not exactly know what I would talk about. I was boiling inside with doubt: should I talk about what I had prepared for the panel or should I just go ahead and speak about the events in Egypt, my mixed feelings, and connections to the South African past of reconciliation? During the panel, two of my colleagues went before me to share their ideas with the public on the topic. I was unsure about my topic until the last minute, but then when it was my turn and I looked out at the audience, the dynamic of the room decided for me. I started talking about the conditions for societal change in favor of inclusion of difference but then made connections among the Egyptian “Spring of freedom,” the Iranian revolution, and the South African approach of change. The balance I tried to create between emotion and academic knowledge seemed to work. I felt the connection to the public and told them that as an ex-revolutionary who believed in rapid and drastic change I had reevaluated my position and believe now that small movements (or micro-emancipations) with thoughtful actions provide the most durable possibilities for inclusive change (a change that includes opposition). My preference at this moment is quite consciously for small movements with durable and great impact.

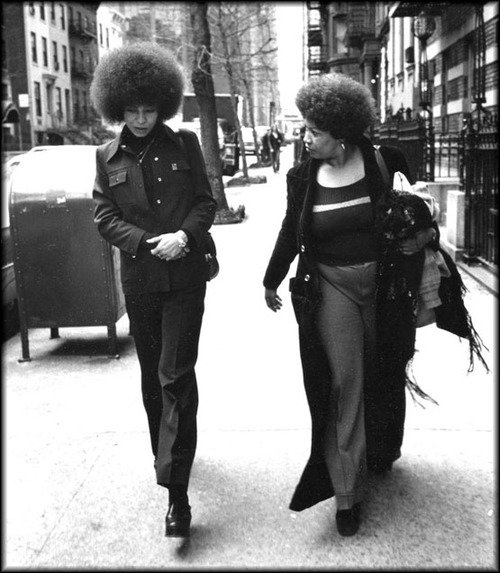

My inspiration comes from Black feminists in the US who chose for the creation of safe spaces in the margins of the center of action (as opposed to what Black civil rights activists of the time did) to focus on self-definitions rather than reproductive or re-active positioning within the dominant discourse. “Creating safe space” as resistance (Collins 1991) introduces a clear distance from “the center” through which individuals get the chance to distance themselves from its normalizing impact in order to reflect. But it also enables inserting reflection into the act by producing alternative narratives that make a difference. In this way stories were produced through the patient collection of oral histories and the sharing of those stories with different generations of women. This allowed those women to combine painful moments of suppression and humility with powerful moments of resistance and pride. Those stories, the experienced knowledge, and the combination of pain and pride provided new generations of black women the strength to become successful in different fields of US society today. The stories of the generations showed them how the route of strength and pride is possible even in the most suppressive situations such as slavery and legalized racism. The novels of black writers gave generations of women the imagination to dream of what seemed impossible. Jazz and blues gave them the possibility to create a sense of solidarity and safety through the art of listening. By making the choice of slow production of oral history, literary writings, and music, this generation of women created a foundation which inspires many others. Their production from the position of difference created spaces for possibility within the structures of impossibility.

When he was talking of these projects in townships I was reminded of the work of Russian Anton Makarenko on alternative pedagogy. During the Iranian revolution we read his book and watched the film based on it. Through Makarenko’s work I came to understand the social conditions that create criminal and/or abnormal behavior and that changing those conditions would create possibilities for changing behavior. I asked Neville whether he knew this work and he replied: “Of course, his ideas are the point of departure for our work in the townships.” I was completely surprised and could not entirely grasp the power of the connection I felt at that moment. It was the kind of connection that transcended all the possible categories of difference; age, race, gender, religion, culture, time, continents, even more…There were even more subjects that showed this sense of connectedness. An example is a project Neville discussed in the agricultural context, experimenting with co-operation. Then again I saw the connection with the novels of Mikhail Sholokhov (another writer who had a great influence on me during the revolutionary years). These connections were again familiar for Neville.

“…[M]y memories were given back to me as a precious gift…This experience had another impact as well: it returned my original ideals.”

Words cannot describe the feeling I had when talking to Neville. I was completely mesmerized to find such an unexpected soul-mate with whom I could share the experiences I had not shared for more than 30 years. I had not shared these ideas with Iranians because I felt that it would be redundant. I felt that non-Iranians would not be able to grasp the intensity of those memories. Yet there I was in South Africa feeling that my memories were given back to me as a precious gift. They mattered even now in a completely different context. This experience had another impact as well: it returned my original ideals.

After the violence I (and my soul mates of the revolution) faced, I felt the ideals of those years were naïve and unrealistic. I tried to translate those great ideals to more practical and reachable ones, which explains my choice for micro-emancipation. Through Neville’s story I could reconnect the old ideals of larger societal change to the idea of small movements. I could see how micro emancipatory movements could have macro impacts and how great idealists could still have a major influence in people’s lives and in the co-creation of better societies. That is exactly the combination we need to create conditions for durable change: we need to stay critical and reflective about the present conditions while translating our ideals into concrete and durable actions for change. As you can imagine, my first visit to South Africa and the diner with Neville will inspire me for years to come in a search for connections that seem impossible and for possibilities within seemingly impossible structures. Even now that Neville has left us behind with the pain of his loss (he died in August of 2012), his ideals and his passion for change are as alive as they can be through sharing his experiences and stories.

Halleh Ghorashi is full professor of diversity and integration at the department of Sociology of the VU University Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Featured image of Banksy graffiti in San Francisco by Thomas Hawk, Some rights reserved