Democracy is not for the faint of heart. It is messy and emotional and taxing. It takes a lot of time to create and maintain and everyone must come prepared with awareness and a good heart. But it’s better than having some power-hungry jerk tell you what to do. So here is a crash course in how democracies work (or don’t). This essay is intended for fledgling democratic group members trying to organize and be politically effective.

Democracy is not for the faint of heart. It is messy and emotional and taxing. It takes a lot of time to create and maintain and everyone must come prepared with awareness and a good heart. But it’s better than having some power-hungry jerk tell you what to do. So here is a crash course in how democracies work (or don’t). This essay is intended for fledgling democratic group members trying to organize and be politically effective.

By Hollis Glaser, PhD

First, it is best to think of democracy not as an end-state, but as an ever-changing, dynamic field of human activity, predicated upon the PROCESS of democracy. There is no such thing as a pure democracy. However, it may be useful to think about a continuum with an ideal democracy on one end and a fictional pure dictatorship on the other. This fictional dictatorship would look like one person making all decisions with no feedback or questions from those below. The ideal democracy would be an absolute sharing of power, which is close to impossible.

As will be described in more detail below, the defining characteristics of a democracy are: shared power, attention to process, awareness of inequality. (Alternatively, dictatorships are defined by power-hoarding, focus on ends, apathy toward inequality or unfairness.)

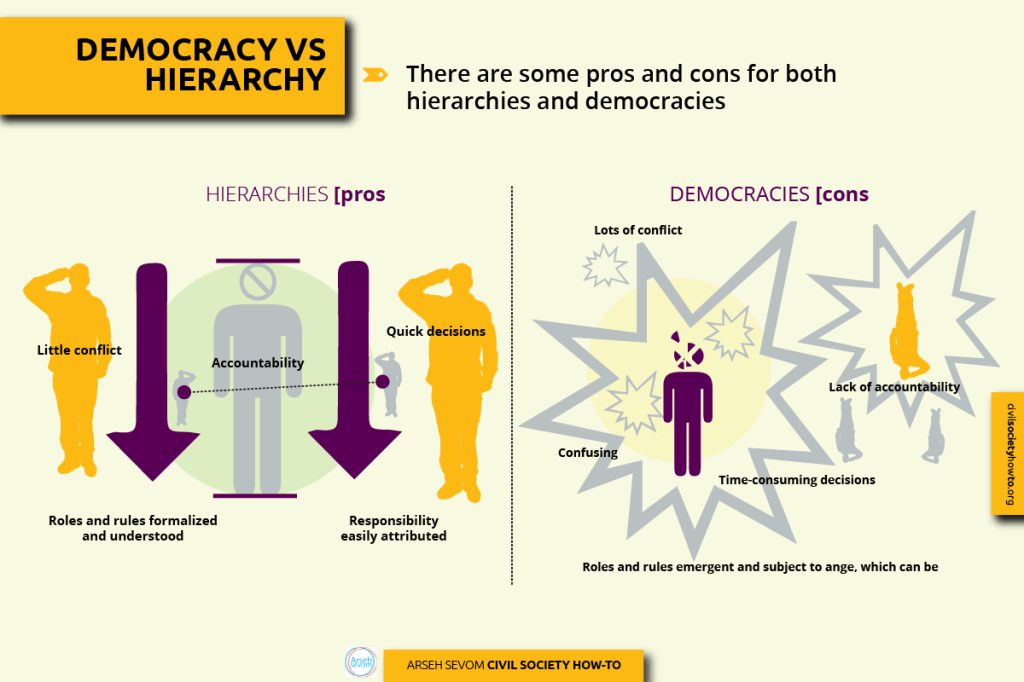

Pros and Cons

Despite the abuse dictatorships wield and the idealism of democracy, there are advantages and disadvantages to both. I assume you understand the distinct disadvantages of hierarchies and the attractiveness of democracies. But hierarchies also have some advantages and democracies have some faults.

| Hierarchical advantages | Democratic disadvantages |

| Little conflict | Lots of conflict |

| Quick decisions | Time-consuming decisions |

| Responsibility easily attributed | Responsibility diffused |

| Roles and rules formalized and understood | Roles and rules emergent, which can be confusing |

| Accountability | Lack of accountabilty |

Power

The most fundamental difference between a dictatorship and a democracy is that dictators hoard power and democracies share or distribute power. Power is built upon resources which include:

- Land

- Money

- Guns

- Military

- People

- Information

- Technology

Dictators control resources. They lock down the internet and other sources of information. They control the military, the natural resources, the land, the people, and get rid of anyone who can threaten that control.

Democracies, on the other hand, share resources. There are many kinds of resources depending on the particular situation the organization finds itself in.

Democratic Power in Groups

It’s worth making a list of the resources available within your group. This list should detail the talents/skills needed in the organization to be effective. Some people might be good spokespersons, others might have crucial connections, others might be exceptionally smart. And herein lies the problem: some people will have different or more talent and skills than others.

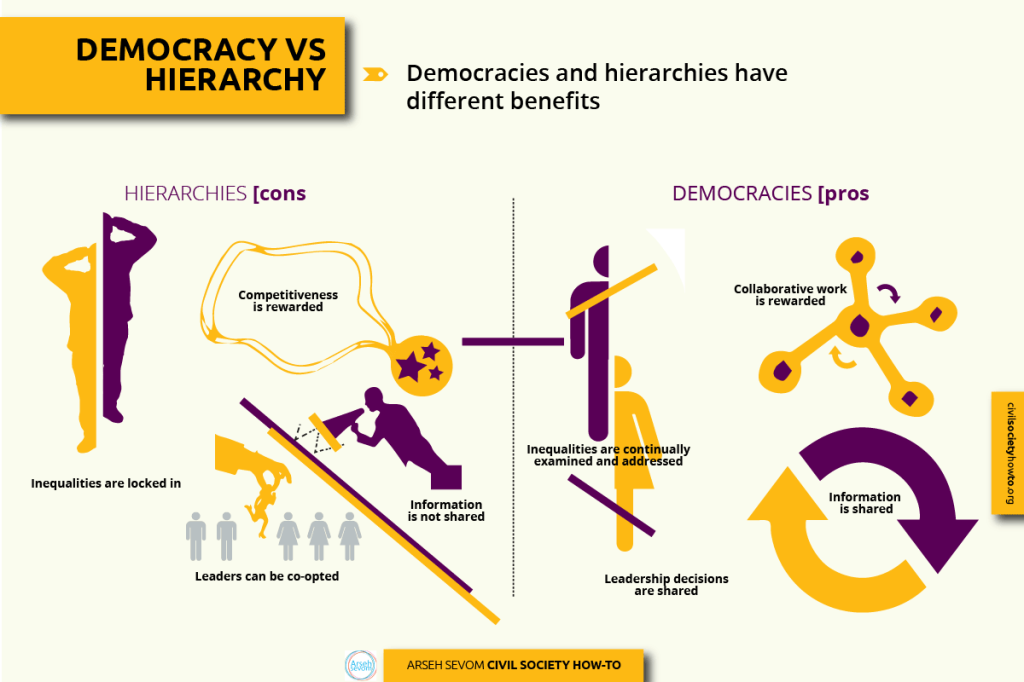

Remember this: there is no pure democracy. All groups, all relationships, have power inequalities. Hierarchies lock in those inequalities and don’t talk about them.

Democracies negotiate those power differences through communication. As you organize, your decisions about your group will be between what aspects of your organization will be democratic and what will be more authoritarian or hierarchical. In other words, democratic group members see the inequalities and talk about them openly.

You have to talk about these inequalities that emerge because if you don’t, your group will become an informal hierarchy with a lot of resentment in it. For example, perhaps someone in your group has a strong and close connection to a key journalist who is helpful in getting your message out. That person, by default, will have a lot of power in the group. And maybe there is no way to share that resource because the journalist doesn’t trust anyone else and will only work with this one person. OK. That’s how it is. But everyone should know that, should be able to talk about it in the group, and should be careful not to let this one person decide all matters with this journalist or have too much power in other situations.

Time is also a resource, perhaps our most precious. Think about that and ask good questions of one another about it. Do some people have more time than others? How is the group using its time together? What tasks/decisions take a lot of time?

Another way to think about democracy is its emphasis on process. Everyone has to pay attention to how the group is working, not just the end point. If you focus only on the end point, then “whatever means necessary” can become the rule that might include some people running over others just to get the job done. And there goes your democracy.

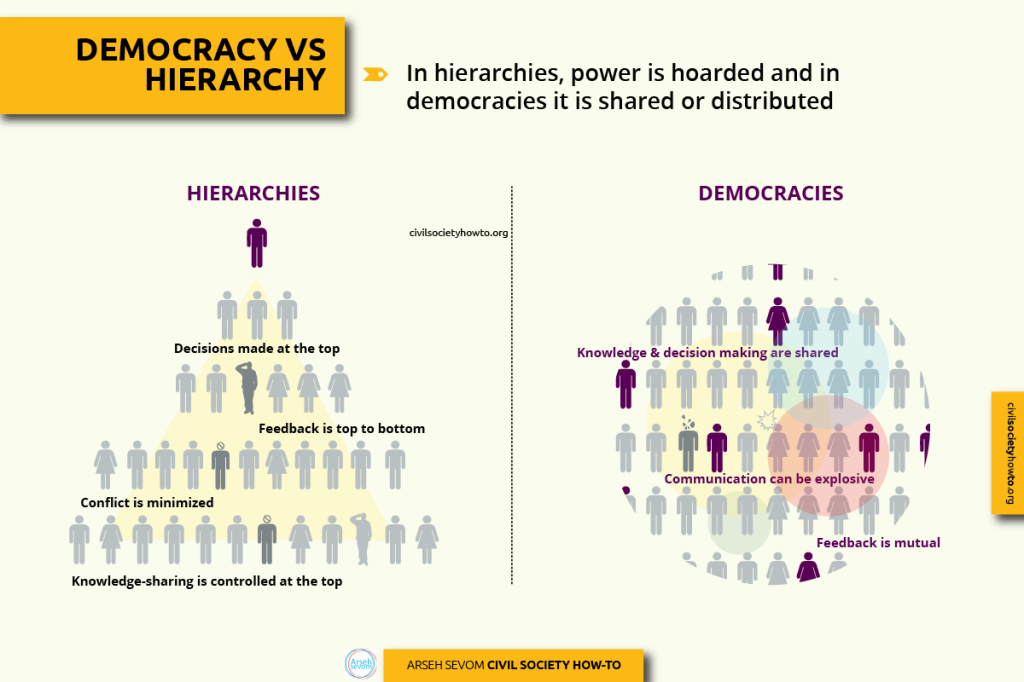

The way you focus on the process is by paying attention to the way these particular organizational communication tasks are performed: decision-making, conflict-resolution, knowledge-sharing, and feedback. Hierarchies and democracies perform these tasks very differently.

| Hierarchies | Democracies | |

| Decision-making | Made at the top | Shared |

| Conflict-resolution | Minimized | Explosive |

| Knowledge-sharing | Controlled at the top | Mutual |

| Feedback | Top to bottom | Mutual |

![]() Remember this: there is no pure democracy. All groups, all relationships, have power inequalities. Hierarchies lock in those inequalities and don’t talk about them.

Remember this: there is no pure democracy. All groups, all relationships, have power inequalities. Hierarchies lock in those inequalities and don’t talk about them.

Decision-Making

Democracies share decision-making. This is what makes them democratic and also rife with conflict. The person at the top of a hierarchy can make decisions that subordinates must follow whether they like it or not. Democratic groups share decision-making, disagree, fight, get emotional, and take longer to act and come to decisions.

It’s a good idea to decide which decisions (yes, decide about decisions) will be made with many people involved and which can be relegated to a few in order to save time. Every time you bring an issue to the group, that means more time spent on it, more opinions and the possibility of more conflict. Some decisions are worth the effort because they are important or central to the group’s identity or you need everyone on board for it to happen. But some decisions really are not worth the time and energy for a big decision-making meeting.

For example, platoons in combat in emergency situations need one person to make the decisions and need trained troops to follow that decision, no matter how they feel or how scared they are. This discipline is what makes an effective armed force.

In the opposite direction, a classic example of time-consuming democratic decision-making was the way the American Quakers, a radical democratic organization, decided what they would do about slavery in the 17th and 18th centuries. They vehemently disagreed on its morality but were committed to consensus, to everyone agreeing about major decisions before they would take action. I mean everyone, not the majority. It took them over 100 years to create that consensus around slavery. But once they did, the Quakers were a major force in the abolition movement.

Conflict Resolution

Conflict-resolution is another crucial process that has to be taken care of. Beware: there is a lot of conflict in democratic groups because there is equal power and everyone gets their say and nobody thinks alike. (Hierarchies suppress conflict.) Along with conflict comes a lot of emotion: anger, hurt, passion, tears, yelling, sulking, etc. As a result, everyone needs to be ready for the emotion. Ideally, everyone should get trained in conflict-resolution. However, in lieu of a full-blown day-long training session, the following information will help.

The first thing to do is distinguish among the different kinds of conflicts. Some conflict is healthy because it is helping people analyze problems and get all perspectives aired. These arguments are about ideas or ways to accomplish goals. They should feel like a really interesting discussion.

Democratic groups share decision-making, disagree, fight, get emotional, and take longer to act and come to decisions.![]()

Other conflicts are destructive. These are power-plays. They occur when people are trying to “win” and make others “lose” to get more power in the group. When people’s egos have taken over the conflict, when they are trying to “beat” the other party, and they have lost sight of the problem, then the conflict is escalating. If you find yourself or others in the midst of a destructive, escalating conflict, remember the following five points:

- People in conflict mirror one another’s attitudes. This means that they both think of the other in identical terms: being stubborn, arrogant, careless, etc. They both attribute the exact same motives to the other. It’s like a weird law of nature. Really. It happens in every single conflict. Bush and Bin Laden talked about each other in almost identical terms: as outlaws and heathens and such. So if you think the other person doesn’t respect you, they are thinking you don’t respect them. Keeping this in mind will help you be more reflective of your behavior and how you have contributed to the conflict.

- People in conflict mirror one another’s behaviors. (Actually this happens in all kinds of communication situations.) So, if one person starts yelling, so will the other. If one person starts cursing, so will the other. If one person starts calling the other names, it will come back at them. Pretty soon you’re talking about the other person’s mother and then the only place to go is physical abuse. This is called reciprocity. It also means that if one person takes a deep breath and explicitly verbally appreciates the other person, that will also come back to them.

- Assume the other person has good will. Do not let yourself think or let others talk badly about anyone in conflict. Recognize that everyone has similar goals and is doing the best they can. Feeling and saying negative things about the other leads to a destructive conflict. It also destroys the cohesiveness of the group.

- Focus on the problem, not the person. If you are in a conflict with someone, that means that you are in some kind of dependent relationship. You are bound in some way. If you weren’t, you would simply walk away from this person. But you can’t walk away. You’re in a group together, a group you’re both committed to that is doing important work. Remember that. What you have in front of you is a mutual problem. So you work on the problem together. An excellent way to do that is to ask each other, “What do you need?” And then, “How can we get both of our needs met?”

- De-escalate the conflict by talking softer, verbally appreciating, and complimenting the other person. Again, you have mutual goals. The point is not to lock into each other in a destructive cycle that zaps the energy of the entire group. The point is to effect change in the world. So start with yourself and the group (to be somewhat trite) and be careful with your speech. Do not insult the other person. Stay focused and respectful.

Knowledge-sharing

The heart of democracy is information. Having full access to important information is what defines a democracy. The First Amendment of the United States is what makes America so vibrant and dynamic and interesting. Everyone in your organization should know as much as they can about what is going on. This is very easy to do in the digital era. Have an archive where all important documents, proceedings, minutes, decisions can be accessed easily by everyone.

Feedback

In any organization, people need to give and receive feedback about how they’re doing. It is a difficult task that very few people enjoy—either giving or receiving. It is a task rife for conflict, especially in a democracy. In a hierarchy, the boss gets to give feedback to subordinates and often there is a formal and anonymous method for subordinates to give feedback to their superiors. If there is no formal method, either the feedback doesn’t happen or it happens ineffectively. Your group has to figure out a way to do this and it should be formalized, meaning the process needs to be agreed upon and written down. Here are a few rules to make this an effective task.

- Everyone gets feedback on how they are doing their job(s)

- Set aside periodic feedback sessions where the parties have a chance to prepare

- No more than 3 negative items at a time

- Be specific

- Focus on behavior

- Only comment on things the person can change

- Make sure positive feedback is included (no limit on positives)

- Sensitive matters should be handled sensitively and maybe privately

Leadership

The heart of democracy is information ![]()

A last word about leadership: Leadership is about helping people. It is not about getting power. You will naturally have some people in the group who emerge as leaders. These are the people who are helping the group move along in the desired direction. It means that people trust them and follow them to some degree. This is a fine line the group has to walk and one that should be talked about (like everything else). On the one hand, it’s great to have people be able to share their natural talents and move the group along. On the other hand, if they stay in that position for too long, you can move more toward a hierarchy on the continuum than you want to be. Democracies rotate their leaders. It is crucial to give people a chance to develop their leadership skills (however that might look—running a meeting, speaking at a rally, organizing the volunteers).

Strong Leaders Can Be Co-opted

The other danger of having strong leaders is they can be co-opted by the hierarchy you are fighting. Co-opting leadership is absolutely a sure-fire, tried-and-true way to neutralize your organization. The opposition simply focuses on the leaders and persuades them to lead your group in a way they want.

The lack of leadership is why the Occupy Wall St. movement was so beautiful in its early days when it was encamped in Lower Manhattan. They truly had no leadership. When the police wanted to get them to move, there was nobody they could speak with who the entire group would follow. So the police were stymied. The downside of this lack of leadership (as many people have noticed) was there was no clear vision being articulated by the movement. Much of the country and world was not clear about what Occupy Wall St. was about or what they wanted.

You must be cognizant about what is happening with your leadership in the group. There is no right answer here and no tips I can give you. It might be that you’ll have to sacrifice some of your democratic leanings in order to accomplish a larger goal. You will just have to figure out that balance among yourselves. Because, of course, you don’t want to beat your opponent by ending up exactly like them.