The Death of the “Twitter Revolution” and the Struggle over Internet Narratives

March 15, 2011The death of the “twitter revolution” and the struggle over internet narratives

March 17, 2011Iran’s Reformists and Activists: Internet Exploiters

by Babak Rahimi and Elham Gheytanchi

View as single page

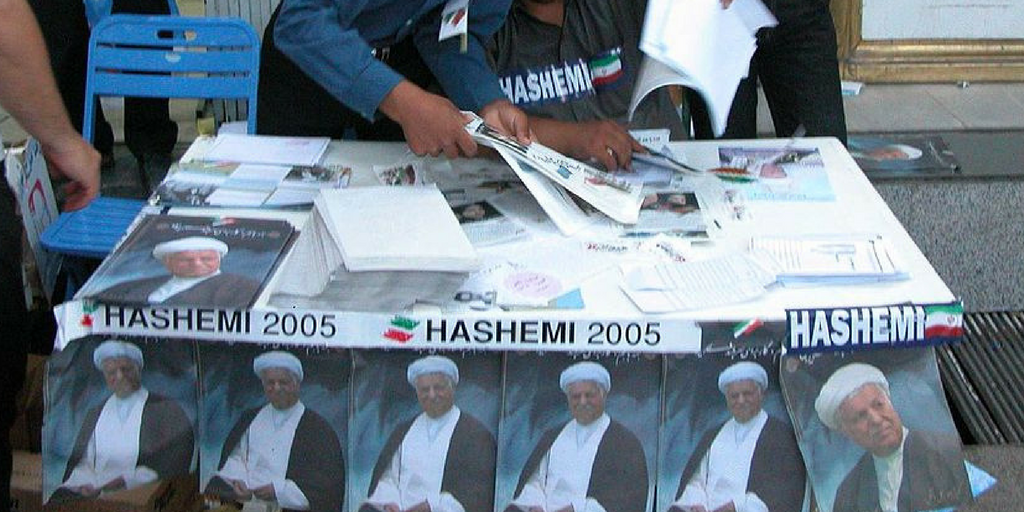

It has become increasingly accepted that the Iranian presidential election of 2005, which brought to power hardline politicians like Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, caused a major decline of dissent. Under Mohammad Khatami’s presidency, Iranians, especially the youth, confronted the regime with the hope of transforming the autocratic political system into a more democratic one. The current public, however, remains largely indifferent to politics, despite being subjected to the crushing domination of increasingly authoritarian rule. This political culture of apathy is mainly, it is argued, a by-product of the Khatami regime’s failure to meet earlier public demands for democratic change.

Although their 2005 electoral triumph provided the hardliners with a golden opportunity to inhibit dissent, it failed to solve most of the inherent flaws of the Islamic Republic and, consequently, left the root of dissent very much intact. As a result, in the context of mounting economic and social problems, including ongoing tension with the United States, Iran’s theocracy continues to face an increasingly dissatisfied population. Indeed, as the state continues to deny the public’s aspirations for civil rights and democracy, Iranian dissident groups have persisted in fighting back, using alternative forums of communication, such as the Internet, to facilitate their expressions of discontent.

The Internet and Social Movements

In the context of these burgeoning social movements, the Internet has become a powerful platform for opposition. Online activism has served as an extension of Iranian dissident groups’ channels of expression, allowing them to circumvent the established propaganda mechanisms and more directly exchange information and mobilize protests with other social movements. The result is a sophisticated operation allowing for the development of solidarity and sympathy from around the globe in a way that would have been difficult, if not impossible, with traditional means of communication.

While Iran’s leaders have been trying to avoid Internet-induced unrest since 2001 by, among other things, limiting citizens’ use of the new technology, they are slowly accepting the reality that the Internet today has come to pose a serious threat to their power. It is clear that the government will not be able to counter this threat with the ease and effectiveness that has traditionally marked its response to other means of communication.

The political use of the Internet by two of Iran’s distinct social movements, women’s-rights activists and the reformist ulama (clerics), reveals the innovative force of this new medium. It demonstrates how the new technology can enable the formation of new civil spheres, or “virtual domains,” to defy authoritarian control over the ideas of civil society and symbols of justice. These civil spheres constitute simultaneous symbolic constructions and regulative judgments in the name of civil rights and democratic rule. Such “civil repairs,” as the sociologist Jeffrey Alexander has described them, provide a model of values for broadening civil solidarity to which the Iranian activists and the reformists look as they voice their demands. (1)

REFORMIST ULAMA AND THE INTERNET

Since the founding of the Islamic Republic in 1979, the reformist ulama’s opposition to the ideology of velayat-e faqih (rule by an Islamic jurist), which vested ultimate authority in the unaccountable and unelected office of jurisconsult (vali-faqih) as the “guardian” of the people, has posed a serious threat to the autocracy’s legitimacy. These nonestablishment clerics have criticized the absolute authority of the mujtahid (Muslim scholar, a precondition for the office of vali-faqih) advocated by the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini (1902-89), as “un-Islamic.” They have also identified this vision for a nation, which requires clerical sovereignty over day-to-day state and political affairs, as the reason for the corruption of Islam. (2)

Dissenting Ulama

Although not a monolithic community of scholars, these clerics have brought a powerful reformist discourse into the post-revolutionary political culture of the religious community by identifying the theocratic foundation of velayat-e faqih as tyrannical and undemocratic. Such a foundation, they argue, inherently contradicts the flexible and pluralistic spirit of the Islamic faith. Through their religious networks, composed of seminaries (hawza), representatives and young jurists, the reformist ulama have succeeded in disseminating this and other anti-establishment views, as well as pushing for a shift in the conception and practice of Islam in the Iranian political sphere.

A gradual shift in the discourse and practice of transnational Shii authority is taking place, led by prominent figures such as Muahmmad Husain Fadlallah (1935-2010) in Lebanon, Ayatollah Ali Sistani (b. 1930) in Iraq, and a number of Iranian dissident ulama like Hussain Kazemeini Boroujerdi (b. 1954), Hassan Yousefi-Eshkevari (b. 1949), Hojjat al-Islam Mohsen Kadivar (b. 1959), Yosuf Sanei (b. 1929) and Mohammad Mojtahid Shabestari (b. 1936). In Iran, the enterprise of democratic-minded ulama has produced a reconceptualization of religious authority that promotes neither autocracy nor theocracy. These dissenting ulama demand “Islamic justice” through democratic ideals of accountability, pluralism and civil rights–including women’s rights–backed by the Islamic ideals of piety, which they interpret as empowering a just political community.

Democratic Tradition of the Ulama

The idea that the lowest level of political involvement entails the highest form of religious piety has a long history in the scholarly circles led by Shaykh Mufid (d. 1022) and Khawaja Nasir-al-Din Tusi (d. 1274). These Shii scholars were among the first to call for the systematic teaching of Shii scholarship and the formation of the seminary institutions in the Iraqi city of Najaf. Theirs is a religious tradition that assigns to a cleric the primary social roles of community leader and moral adviser. The real authority of the ulama, according to this tradition, lies in the community: the ulama are the custodians of the common good, responsible for the welfare of orphans, widows and the poor during the long period of “occultation” (ghayba), from now until the end of time, while the Twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, is believed to be hidden from sight. (3) During the absence of Mahdi, who will eventually establish on earth the ultimate government of justice and peace, a jurist should keep his distance from any form of temporal power, as it is inherently illegitimate.

The central aim of the contemporary reformist ulama is to renew this tradition with an added emphasis on the popularly elected government as a guarantee against arbitrary power. The notion of separation between spiritual and temporal authority is central to this discourse, since it is in this division of power that citizens are able to find a balance between the divine and secular spheres of life. This particular structure of clerical-state relations was promoted in the writings of the pro-democracy ulama of the Constitutional Revolution (1906-11), which helped unleash one of the first constitutional revolutions on the continent of Asia. (4) Inspired by the works of influential clerics like Mohammad-Hossein Naini (d. 1936), who emphasized government accountability while still acknowledging Islam as a source of legislation, these reformist ulama now seek to revive the idea of popular sovereignty as a central ideal of Islamic governance and rescue religion from political micromanagement by the state.