Creating the Impossible: The Invisible Network of Britain’s Activist Subculture

March 26, 2011

Berlin, Bam, New Media, and Transnational Networks

April 2, 2011Iran’s Reformists and Activists: Internet Exploiters

by Babak Rahimi and Elham Gheytanchi

It has become increasingly accepted that the Iranian presidential election of 2005, which brought to power hardline politicians like Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, caused a major decline of dissent. Under Mohammad Khatami’s presidency, Iranians, especially the youth, confronted the regime with the hope of transforming the autocratic political system into a more democratic one. The current public, however, remains largely indifferent to politics, despite being subjected to the crushing domination of increasingly authoritarian rule. This political culture of apathy is mainly, it is argued, a by-product of the Khatami regime’s failure to meet earlier public demands for democratic change.

Although their 2005 electoral triumph provided the hardliners with a golden opportunity to inhibit dissent, it failed to solve most of the inherent flaws of the Islamic Republic and, consequently, left the root of dissent very much intact. As a result, in the context of mounting economic and social problems, including ongoing tension with the United States, Iran’s theocracy continues to face an increasingly dissatisfied population. Indeed, as the state continues to deny the public’s aspirations for civil rights and democracy, Iranian dissident groups have persisted in fighting back, using alternative forums of communication, such as the Internet, to facilitate their expressions of discontent.

The Internet and Social Movements

In the context of these burgeoning social movements, the Internet has become a powerful platform for opposition. Online activism has served as an extension of Iranian dissident groups’ channels of expression, allowing them to circumvent the established propaganda mechanisms and more directly exchange information and mobilize protests with other social movements. The result is a sophisticated operation allowing for the development of solidarity and sympathy from around the globe in a way that would have been difficult, if not impossible, with traditional means of communication.

While Iran’s leaders have been trying to avoid Internet-induced unrest since 2001 by, among other things, limiting citizens’ use of the new technology, they are slowly accepting the reality that the Internet today has come to pose a serious threat to their power. It is clear that the government will not be able to counter this threat with the ease and effectiveness that has traditionally marked its response to other means of communication.

The political use of the Internet by two of Iran’s distinct social movements, women’s-rights activists and the reformist ulama (clerics), reveals the innovative force of this new medium. It demonstrates how the new technology can enable the formation of new civil spheres, or “virtual domains,” to defy authoritarian control over the ideas of civil society and symbols of justice. These civil spheres constitute simultaneous symbolic constructions and regulative judgments in the name of civil rights and democratic rule. Such “civil repairs,” as the sociologist Jeffrey Alexander has described them, provide a model of values for broadening civil solidarity to which the Iranian activists and the reformists look as they voice their demands. (1)

REFORMIST ULAMA AND THE INTERNET

Since the founding of the Islamic Republic in 1979, the reformist ulama’s opposition to the ideology of velayat-e faqih (rule by an Islamic jurist), which vested ultimate authority in the unaccountable and unelected office of jurisconsult (vali-faqih) as the “guardian” of the people, has posed a serious threat to the autocracy’s legitimacy. These nonestablishment clerics have criticized the absolute authority of the mujtahid (Muslim scholar, a precondition for the office of vali-faqih) advocated by the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Ruhallah Khomeini (1902-89), as “un-Islamic.” They have also identified this vision for a nation, which requires clerical sovereignty over day-to-day state and political affairs, as the reason for the corruption of Islam. (2)

Dissenting Ulama

Although not a monolithic community of scholars, these clerics have brought a powerful reformist discourse into the post-revolutionary political culture of the religious community by identifying the theocratic foundation of velayat-e faqih as tyrannical and undemocratic. Such a foundation, they argue, inherently contradicts the flexible and pluralistic spirit of the Islamic faith. Through their religious networks, composed of seminaries (hawza), representatives and young jurists, the reformist ulama have succeeded in disseminating this and other anti-establishment views, as well as pushing for a shift in the conception and practice of Islam in the Iranian political sphere.

A gradual shift in the discourse and practice of transnational Shii authority is taking place, led by prominent figures such as Muahmmad Husain Fadlallah (1935-2010) in Lebanon, Ayatollah Ali Sistani (b. 1930) in Iraq, and a number of Iranian dissident ulama like Hussain Kazemeini Boroujerdi (b. 1954), Hassan Yousefi-Eshkevari (b. 1949), Hojjat al-Islam Mohsen Kadivar (b. 1959), Yosuf Sanei (b. 1929) and Mohammad Mojtahid Shabestari (b. 1936). In Iran, the enterprise of democratic-minded ulama has produced a reconceptualization of religious authority that promotes neither autocracy nor theocracy. These dissenting ulama demand “Islamic justice” through democratic ideals of accountability, pluralism and civil rights–including women’s rights–backed by the Islamic ideals of piety, which they interpret as empowering a just political community.

Democratic Tradition of the Ulama

The idea that the lowest level of political involvement entails the highest form of religious piety has a long history in the scholarly circles led by Shaykh Mufid (d. 1022) and Khawaja Nasir-al-Din Tusi (d. 1274). These Shii scholars were among the first to call for the systematic teaching of Shii scholarship and the formation of the seminary institutions in the Iraqi city of Najaf. Theirs is a religious tradition that assigns to a cleric the primary social roles of community leader and moral adviser. The real authority of the ulama, according to this tradition, lies in the community: the ulama are the custodians of the common good, responsible for the welfare of orphans, widows and the poor during the long period of “occultation” (ghayba), from now until the end of time, while the Twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, is believed to be hidden from sight. (3) During the absence of Mahdi, who will eventually establish on earth the ultimate government of justice and peace, a jurist should keep his distance from any form of temporal power, as it is inherently illegitimate.

The central aim of the contemporary reformist ulama is to renew this tradition with an added emphasis on the popularly elected government as a guarantee against arbitrary power. The notion of separation between spiritual and temporal authority is central to this discourse, since it is in this division of power that citizens are able to find a balance between the divine and secular spheres of life. This particular structure of clerical-state relations was promoted in the writings of the pro-democracy ulama of the Constitutional Revolution (1906-11), which helped unleash one of the first constitutional revolutions on the continent of Asia. (4) Inspired by the works of influential clerics like Mohammad-Hossein Naini (d. 1936), who emphasized government accountability while still acknowledging Islam as a source of legislation, these reformist ulama now seek to revive the idea of popular sovereignty as a central ideal of Islamic governance and rescue religion from political micromanagement by the state.

Opposition to Clerical Authority over the State

The 1978-79 Islamic revolution radically altered the traditional status of the ulama. Khomeini’s vision–that the clerics should be more than public agents of the Hidden Imam and should instead claim authority over state power–encountered opposition from some of the most senior ulama in the 1980s, most notably Ayatollah Shariatmadari (1905-86) and Ayatollah Mohammad Shirazi (1928-2001), who were placed under house arrest as a result of their opposition. (5) In the face of waves of opposition during the Islamic Republic’s initial Jacobin phase (1979-88), the state clerics adopted various institutional attempts to tame the dissident ulama, especially the most senior ones, whose reach went beyond the borders of Iran and included countries like Iraq, Lebanon and Pakistan, where Tehran had strategic ambitions to spread its revolutionary brand of Shiism.

With the aim of monopolizing religious discourse in Qom, conservative clerics either adopted “propagation” strategies or enforced legal measures to stifle dissent within the religious establishment. The propagation strategies were initiated in the early 1980s with the formation of new ideological centers, most notably the Dafiar-e Tablighat-e Islami-e Howzeh-ye Ilmiyeh-ye (The Office of Islamic Propaganda of the Scientific Seminary), which oversaw the propagation of Khomeini’s version of Shiism in the seminary city of Qom. As dissension strengthened with the rise of execution of opponents and the uncertainty of a seemingly unending war with Iraq in the later half of 1980s, the state was forced to take harsher measures, such as the institutionalization of the official clerical court, the Special Court for the Clergy (SCC) in 1987, which operates outside of the civic judiciary and aims at stifling dissent from clerical circles by identifying and charging “counterrevolutionary” ulama for their opposition to the regime.

Yet the reformist ulama continued their opposition. When Ayatollah Ali Khamenei was selected by the Assembly of Experts, a clerical body in charge of supervising and electing a supreme leader to succeed Khomenei in the summer of 1989, a number of senior clerics openly questioned his religious qualifications and credentials, as well as his authority to issue religious rulings. But Khamenei’s succession led to the consolidation of the absolutist institution of the velayat-e faqih, which brought the seminaries in Qom under greater supervision by conservative clerics.

The Election of Khatami

The 1997 presidential elections that marked the impressive victory of Hojatoleslam Mohamad Khatami, however, provided a new opportunity for the reformist ulama. The late 1990s saw a boom in dissident clerical writings in journals, newspapers and books. The works of clerics like Kadivar, Shabestari and Yosufi Eshkevari, which underwent a number of printed editions, unleashed a series of often-heated public debates on the role of religion in politics. (6) But, as the Iranian public sphere expanded with the relative easing of censorship restrictions under the Khatami government, the reformist ulama faced the harsh measures of the conservative judiciary against reformist print media. A new means of communication was needed to circumvent their censorship, and that means of communication was the Internet.

The Uluma and the Internet

When first introduced in the early 1990s in Iran, the Internet provided an added medium for publishing works of jurisprudence and political pamphlets that were usually blocked in the traditional print media by the conservative clerics. (7) For the most part, the reformist clerics continued to use the conventional means of print publication, but the Internet had a more modern appeal; it allowed them to publish their views to not just a local audience, but regional and global ones as well. Most important, however, the new technology provided a new communicative sphere, a virtual domain that operated beyond the supervision of state authorities.

While the digital space brought to the younger generation the freedom to anonymously interact, exchange ideas, and write about sex and other social taboos, the reformist ulama began to use the new forum to discuss and debate political and theological topics of a complex and polemical nature that were deemed heretical by the conservative clerics. The target audience was not only the religious establishment; it was also the younger domestic and global audiences whose support would be the key to influencing the policy makers who would refuse them a voice in the mass media as it is strictly supervised by the conservative-dominated censorship machinery. The impact of the Internet on Iranian politics resembles the introduction of earlier information technologies, such as the telegraph in the late nineteenth century and the cassette tapes in the 1970s, which also created new individual and social spaces for dissent. (8)

Blog Locally and Reach Globally

In this light, the use of the Internet by reformist ulama can be defined along two salient dimensions. First, the creation of personalized spaces, both websites and blogs, provided a powerful medium for the clerics, especially the younger, more technologically savvy ones, to reach a wider and younger audience, which in turn increasingly used the Internet to reach out to the world. Second, the new medium helped the ulama access information and communicate with a considerable regional and global reach. This would not have been possible with print publications. The political implications of this online venture were significant, since this new space empowered the reformist ulama to propagate their democratic interpretations of Islam, civil rights and women’s status in Islam without the supervision of the state. This process of empowerment has mainly occurred in two distinct phases.

Confrontational Phase: Montazeri

With the introduction of the Internet to the Qom seminaries in the mid-1990s, a number of reformist clerics experimented with the new information technology. In doing so, they mainly followed a group of reformist activists like Akbar Ganji, Mohsen Sazgara and Said Ibrahim Nabavi, who began to recognize the creative potential of the new technology as an alternative outlet for their discontent with the regime. Reformist followers of the new president, including members of Khatami’s cabinet like Mohammad Ali Abtahi, opened up new websites and weblogs. (9) Their strategy was the same as Khatami’s when he debated online his conservative counterpart, Ali Akbar Nateq-e Nori. (10) The Internet was the best place to directly confront the conservatives without censorship and with accountability to the public.

One of the prominent clerics in this phase of experimentation, which early in Khatami’s presidency became increasingly confrontational, was the Grand Ayatollah Morteza Montazeri. Once a senior intellectual and one of the original drafters of the 1978 Constitution, Montazeri was dismissed by Khomeini as his successor in 1989 for, among other reasons, his criticism of the mistreatment and execution of political prisoners. (11) Although he remained mostly quiet throughout the early 1990s, Montazeri’s sudden arrest in November 1997 for criticizing the spiritual authority of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the successor to Ayatollah Khomeini and the current supreme leader of Iran, ignited anti-government riots and sporadic skirmishes between his supporters and the security forces in cities such as Isfahan and, nearby, Najafabad, Montazeri’s city of birth.

Inclusive Interpretation of the Iranian Constitution

In contrast to the clerical officials in Tehran, Montazeri advocated a more inclusive, pluralistic interpretation of the Iranian constitution that would give the Iranian populace the right to elect all its leaders, including the supreme leader, who is currently appointed by a body of high-ranking clerics, the Assembly of Experts. By advancing the idea that the clerics must defend the rights of people, especially women, and seek to establish a government that is democratic and yet embodies the ideals of Islamic justice, Montazeri recognized an essential fact: the way to establish a just government is to acknowledge that people understand their own interests. Presuming the masses are rational, he anchors his interpretation upon clerics as advisers (with the power to determine what is just or unjust) in quest of the common good rather than absolute power.

Since 1997, Montazeri faced several attacks by the regime, and he fought back. For instance, in 2000, he threatened the conservative establishment with jihad if Ayatollah Khamenei dismissed President Mohammad Khatami and imposed martial law. This was rumored to be a possibility after the assassination attempt against Said Hajjarian, then a reformist adviser to Khatami. In 2002, while still under house arrest, Montazeri criticized Khamenei’s call for the destruction of Israel and endorsed peaceful coexistence between Palestinians and Israelis. Under Khatami’s presidency, Montazeri’s seminarians, who in the early 1990s clandestinely read his banned books, began to openly spread his ideas at mosques and public gatherings in Isfahan, Qom and Tehran. Despite the gradual increase of censorship in the second half of Khatami’s presidency, newspapers and journals like Farda, Iran Emrouz and Kiyan published Montazeri’s opinions on theology and politics.

Montazeri’s 600-Page Memoir Published Online

The postings on Montazeri’s personal website, which offered detailed information about his biography, religious statements, scholarly texts and discussion on various theological issues, provided a new outlet for the grand ayatollah to express his discontent. For instance, while under house arrest in December 2000, he shocked the conservative establishment when he posted his 600-page memoir. Providing detailed description of some of the most critical moments of the early revolutionary state, including how he tried to prevent the execution of opponents, it was a devastating critique of the Islamic Republic, not only attacking Khamenei and his scholarly credentials, but also rejecting the absolutist ideology of jurist rule, a move considered blasphemous in the eyes of the conservatives.

The state immediately reacted by attempting to filter and limit public access to Montazeri’s website. His seminary also faced renewed threats. (12) Recognizing the potential dangers of the new technology, the conservative-dominated judiciary then began to shut down reformist newspapers such as Neshat, Jameh and Tous and their websites. In November 2001, the judiciary and the powerful Supreme Council for Cultural Revolution implemented further restrictions on the Internet in the same way that they attempted to control satellite television. Internet service providers (ISPs) were forced to remove anti-government and “anti-Islamic” sites from their servers.

These reactive measures in the form of new limitations on Internet use, including the blockage of entire websites, increased in 2002 as the Islamic Republic began to acquire sophisticated filtering programs from China and U.S. companies based in Dubai. The appeal of the Internet seemed to wane in the second part of Khatami’s presidency, as reformists faced continued repression from the conservative factions who in the parliamentary elections of February 2004 consolidated power with the help of the conservative-dominated clerical institution, the Guardian Council, which permitted only conservative candidates to run for election.

Indiscernible Phase: The Case of Sistani

The victory of Ahmadinejad in the 2005 presidential election marked a clear and present danger for the reformist ulama and the future of their online political activism. The increase in censorship by the hardline regime–radical politicians who aimed to resurrect the revolutionary zeal of the early 1980s–was bound to affect the ways in which political dissent could be expressed online. But, while the hardliners held a tight grip on the public sphere through the conservative legal machinery, the 2003 toppling of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime in Iraq by U.S.-led forces heralded a new era of reformist-ulama opposition. With Saddam gone from Iraq, these ulama found a fresh ally in their battle against the conservatives: the Najaf-based Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, whose scholarly credentials surpassed those of the entire clerical establishment in Iran.

The rise of Ayatollah Sistani as the most recognizable senior Shii cleric signaled a revival of traditional Shiism in Iraq that resonated with the ideas of the reformist clerics in Iran. An avid supporter of popular sovereignty and a follower of the pro-democracy clerics of the Constitutional Revolution (1906-11), Sistani was able to put into practice in Iraq many of the arguments the reformists made against the conservative, pro-Khomeini clerics in Iran. (13) His call for a popularly elected council to draft a constitution in November 2003 and for general elections in 2004, aimed at immediately empowering ordinary Iraqis, served as a powerful challenge to Khomeini’s vision of absolutist theocracy.

Sistani’s ascendancy expanded his religious network as well as its financial center, based in the Iranian city of Qom. With a growing annual income of more than $500 million a year, largely gained through religious taxes, his network is rapidly becoming an important force in the transnational Shii community, vying with Khamenei’s in Tehran. (14) Sistani’s expanding network includes the use of information technology operating through computer training centers where Internet use is taught and encouraged among his followers, students and representatives.

Sistani’s Aalulbayat Global Information and Media Center

Sistani’s Aalulbayat Global Information and Media Center hosts the most technologically advanced computer center in Qom, which since 1996 has provided one of the most significant religious websites in the Shii world: www.al-shia.com. It includes Sistani’s personal website, www.Sistani.com, where he offers the faithful his views on issues from religion to politics and current affairs. The center is also a hub for various websites dedicated to spreading the views of more than 50 high-ranking clerics, mostly reformist ulama who include senior figures like Montazeri until his death and Yosuf Sanei. For the most part, the Internet has increased the size and prestige of Sistani’s religious organization in Iran and worldwide.

In 2003, when Sistani’s authority grew because of his popularity in Iran after the fall of Saddam, the center presented the reformist Iranian clerics with a huge opportunity: the chance to further expand their Internet accessibility and express their views online. But this time, they were able to do so under the guise of Sistani’s religious teachings, which implicitly contradicted Khamenei’s religious authority and, consequently, his political power. In matters of religious concern, the reformist clerics were able to challenge Khamenei’s authority by publicly announcing their allegiance to Sistani as the most learned Shii scholar and the most widely followed source of spiritual imitation (marja taqlid). This signaled a major act of resistance from clerics who had been seeking to decentralize the Shii clerical institution and release it from the tight grip of Tehran since 1979.

A Delicate Rivalry

The reaction of the conservative clerics has been less open. Not only is Sistani a major religious figure; he is also highly popular among the Shiis in the region, especially in Iraq and Lebanon, where Iran has vital interests. (15) Sistani, too, has been careful not to upset the conservative clerics in Iran, since many of his seminaries, as well as his financial center, are based in Qom. But he is independent enough not to appease the Iranian regime by indirectly challenging Khamenei’s authority in religious matters, though these confrontations have occurred in subtle ways. Nevertheless, this delicate rivalry between the two religious authorities has provided an opportunity for a camouflaged dissent. This may not have any major consequences in the short term, but down the line it could pose serious challenges to the religious legitimacy of the Islamic Republic.

Yet the confrontational form of clerical resistance continues to be a force in the political landscape of Iran. The October 2006 arrest of Ayatollah Hussain Kazemeini Boroujerdi is a case in point. Since the early 1990s, Boroujerdi’s criticism of Khamenei and his increasing appeal among the religious sections of the Iranian population has posed a major threat to the authorities. It was no surprise that his arrest led to a number of public demonstrations, which were harshly put down by the state. An intriguing phenomenon followed Boroujerdi’s arrest: his followers recorded their clashes with the police and posted the footage on YouTube. (16) Although the YouTube site is blocked in Iran, Boroujerdi’s computer-savvy followers managed to email the recording to the ayatollah’s followers abroad so they would be able to post it online. (17) Iranian viewers were able to see the video by using various antifilter programs to access the site. The use of email and mobile phones was crucial for the way Boroujerdi’s followers communicated beyond the supervision of the authorities to attract international sympathy for their cause. As the case of Boroujerdi shows, the use of information technology carries the potential for a form of dissent that could unleash a new phase in the conflict between reformist and conservative clerics.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Since the end of the eight-year Iran-Iraq War, women’s-rights activists have started a slow but persistent movement for equality. During the reconstruction era, Iranian women gained a substantial presence in the workforce and demanded parity. (18) Many women’s publications, such as Zanan, (19) Zan, and Farzaneh, as well as governmental offices, started working on women’s issues. As the reform movement surfaced in the country, many women’s-rights activists joined forces with reformists, who could not have won the elections in 1997 without overwhelming support from Iranian women. As the reformists experienced backlash from the hardliners, specifically the judiciary, many reformist publications, including women’s publications and those sympathetic with their cause, were shut down. In the absence of political-party competition, women’s-rights activists used the Internet to express dissent and attract international attention.

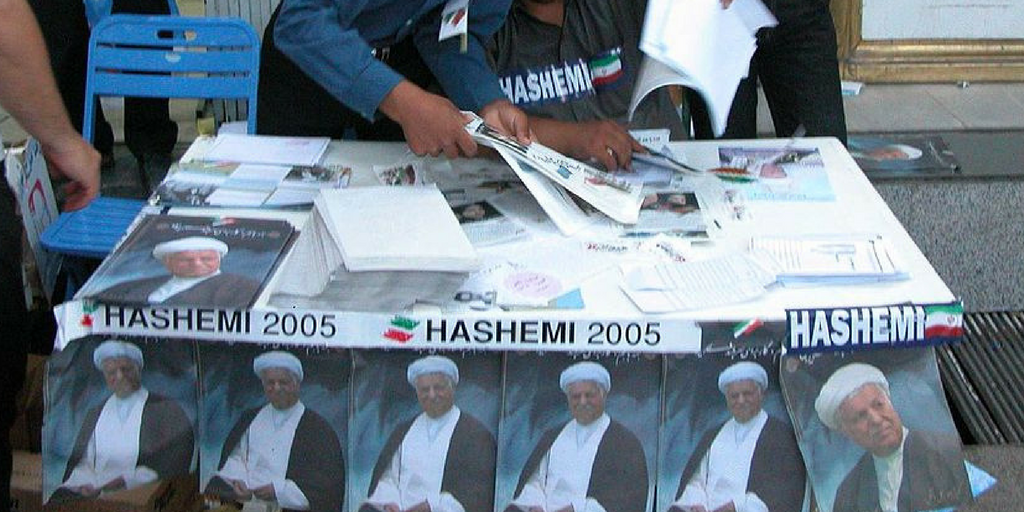

The 2005 elections in Iran showed the uncertainties of politics, (20) but it was also a historic time for women’s-rights activists to claim their independence from political factions. With only 60 percent of eligible voters going to the polls–as many boycotted the elections to protest the Guardian Council’s eligibility process–the reformists candidates Moin and Karrubi were defeated. Rafsanjani and Ahmadinejad earned 21 percent and 19.5 percent of the votes, respectively. In the midst of the second round of elections, the women’s-rights activists organized a peaceful protest on 22 Khordad 1384 (June 12, 2005) in front of the University of Tehran.

2005 Women’s Rights Demonstration

The demonstration announced an independent women’s-rights movement that once again targeted the constitution and the inequalities embedded in the Iranian legal system as obstacles to social justice. The Feminist Tribune, the activists’ website, which is no longer online, posted photos of the relatively calm event. The site was later blocked in Iran.

From the start, the women’s-rights demonstrations called on student activists and others to form a coalition. Women’s nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) from Kurdistan, Azerbaijan (the city of Tabriz), Esfahan and other provinces announced their full-fledged support. Within days, 1,000 people had signed the public declaration, also posted online, calling upon the Iranian state to change discriminatory laws with regard to women. More than 130 weblogs posted their call to action, and many women’s-rights groups in the United States and Europe endorsed the action.

The demonstration in 2005 drew more than 6,000 people, but the state-run news agencies reported only 700. While the opinion polling stayed uneventful, reflecting the boycott by many, the site of the demonstration attracted relative enthusiasm. At the heart of these activists’ efforts was a demand for amending the constitution to limit the future president’s powers to make fundamental political, economic and social changes. Instead of an apathetic boycott, the women’s-rights activists were able to show a political alternative: a nonviolent movement to change the current constitution, which allows the supreme leader and the unelected Guardian Council to approve and ultimately appoint the president of the country.

The Withering of Reform

With only seven candidates successfully vetted by the Guardian Council, conditions were ripe for an independent movement to remind the public of the inherent limitations of the Iranian constitution. After the experience of the reformist government of President Khatami (1997-2005), there was a general feeling of despair among Iranian activists who had previously placed much hope in the “civil society” project. In 2004, Khatami recognized that the reformist camp was withering away. In a tract entitled “A Letter for Tomorrow,” (21) he defended his record within the severe limitations placed on him by radical political factions and the constitution. While Ahmadinejad used the opportunity to win the support of the lower classes with his radical rhetoric, through online campaigns and carefully planned demonstrations, women’s-rights activists seized the moment to demand changes in the constitution that would render any reform effort obsolete.

Ahmadinejad Rises; Civil Society Suffers

After an unsuccessful reform movement, the country seemed to have reverted back to its early revolutionary period. Ahmadinejad’s presidency proved antithetical to social movements. Ahmadinejad was among the volunteers who had joined the ranks of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Council (IRGC) in 1986 to fight in the Iran-Iraq War. A former Sepahi (IRGC), Ahmadinejad is a staunch revolutionary with a mission to defend the Islamic revolution from its enemies inside and outside of the country. These enemies can easily be found, according to the president and his supporters–better known as Osulgarayan (the principalists)–among students and civil-society activists, especially women’s-rights activists, who directly challenge Islamic law (sharia). His platform during his fierce campaign for the presidency did not include a stance on gender inequality; unlike other presidential candidates, he made no effort to target women voters specifically. (22)

Shortly after the elections, Ahmadinejad declared his vision for Iranian society and its nascent movements. Blending nationalism and religious fervor, he made bold statements about the need to become a self-sufficient Islamic country with nuclear energy. Framing this issue as a nationalistic goal for the Islamic nation of Iran, Ahmadinej ad identified internal opposition to his plans as “threats to national security.” (23) When women’s-rights activists gathered to commemorate the first anniversary of 22 Khordad in Haft-e Tir square in the heart of Tehran, more than 30 were arrested by the police, charged with making threats to national security and interrogated by the Ministry of Information.

Violent Suppression of Non-Violent Protesters

The women’s division of the police used violence and coercion to suppress the peaceful demonstration in 2006. Pictures were taken and immediately posted on various weblogs and news sites. Simin Behbehani, the well-known poet, told foreign reporters how she was tasered and beaten along with others who had refrained from physical confrontation with the police. ILNA reported that the head of the judiciary, Alireza Avaayi, had declared that the organizers were legally required to acquire permission from the authorities. The organizers cited their constitutional right (principle 27) to peacefully demonstrate as citizens as long as the demonstration does not oppose Islamic values and no one bears arms. Shirin Ebadi, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate of 2003, filed a legal complaint against the excessive use of force by the policewomen–especially assigned to this case–against unarmed Muslim women who had gathered to peacefully demand equality under the law.

Seven Demands

Although the activists did not get a chance to read their demands, a complete list was posted on blogs and widely distributed on the Internet. (24) In their announcement, titled “100-year-old demands,” the activists appealed to the Iranian state to grant security to Iranian women inside their homes, in their professions and in the greater society. The activists stressed that their nonviolent struggles for women’s equality since the constitutional revolution (1907) have always been within their “senfi” parameters. “Senf” literally means trade/ guild/class; the equivalent of senf union is trade union. By referring to themselves as a senf, these activists are invoking a historical tradition, ranking themselves as a class of workers whose demands are independent of political factions. There were seven items on their list of demands:

1) an equal right to divorce;

2) the outlawing of polygamy;

3) equal rights after marriage;

4) the right to child custody;

5) an increase in the legal age for criminal punishment of girls from nine to 18;

6) equal legal rights for witnesses and judges irrespective of gender; and

7) equal employment rights.

If these rights were not granted to all Iranian women–which would require amending the constitution–the activists declared they would continue their nonviolent protests.

Many Arrested

More than 70 people were arrested, including reporters, student activists and union activists along with a former member of parliament and critic of Iranian detention practices, Ali Akbar Mussavi Khoini. (25) According to the eyewitnesses, police used batons and tasers to physically control the protesters, who did not respond with force. The security forces confiscated many of the demonstrators’ phones in order to halt the distribution of images and news from the scene. But eyewitness accounts and images of police brutality leaked out and were widely distributed on the Internet by bloggers and news websites. The reporters’ union issued a letter demanding the release of ten reporters. Jebhe Mosharekat Iran-e Islami (the Participatory Party of Islamic Iran, the main political party of the reformists) issued a statement condemning the violence by the police as illegitimate and unlawful. The violence against the women’s-rights protesters unified a wide range of activists, including those who were initially opposed to the idea of a demonstration.

The Beginning of the One Million Signature Campaign

Faced with state violence on the one hand and initial opposition by the older generation of women’s-rights activists on the other, young activists decided to change their target audience. Instead of focusing solely on the state, as social movements traditionally do in Iran, they decided to broaden their social base by talking to people, gaining their support and recruiting new members. Upon distribution of their pamphlets in the streets on the eve of the June 12, 2006, event, the activists saw firsthand that they have the potential to draw large crowds sympathetic to their cause. This marked the beginning of the One Million Signature Campaign to change discriminatory laws against women in Iran.

The activists started to gather signatures and listen to women’s narratives as told by people around the country. They published an announcement of their goals on the Internet, a notebook on existing legal limitations on women’s rights, and a form to sign. In face-to-face interactions, the activists engaged with both men and women regarding the gender inequalities embedded in the constitution. Unlike political parties or past social movements with hierarchical power structures, these activists listened to their fellow citizens to create a grass-roots movement directly challenging the Islamic constitution. Instead of advocating on behalf of women or finding leeway in the legal system for their own advantage, as many women do in Iranian courts, (26) the campaigners sought to shape, and in turn were shaped by, a new understanding of a future society in which women’s rights would be fully recognized.

A summary of the initial statement of the One Million Signature Campaign reads as follows:

According to existing laws, a nine-year-old girl can be tried as an adult and, if a court finds her guilty, she can be executed. If a man and a woman become paralyzed in a car accident, the woman can only receive half of what a man receives as damages. If a man and a woman witness a crime, the woman’s testimony is not counted, but the man’s is. According to the law, a father can force his 13-year-old daughter into marrying a 70-year-old man. A mother cannot take full custody of her children under the existing laws nor even make decisions on their financial and medical conditions. A mother cannot legally determine her children’s residency nor travel outside of the country without her husband’s permission. A man can have multiple wives and divorce any or all at any time for whatever reason. (27)

The Spread of the Campaign

Within a year, the campaign spread to 16 provinces throughout the country, and volunteers opened a men’s group as well as a branch in California. In June 2007, following a speech by Hashemi Rafsanjani supporting the activists’ call for equality in diyeh (damages paid to victims as regulated by sharia) for men and women, Ayotallah Sanei and Hojatoleslam Gharavian also announced their support for the equality of men and women in sharia law. (28) Ayatollah Mussavi Tabrizi condemned the charges that women’s-rights activists were a “threat to national security” as “political stigmatization” in order to exclude these activists from the Iranian civil sphere. (29) Other political figures such as Ebrahim Yazdi (from the nationalist-religious faction) and Elahe Koolayi (a member of the sixth parliament) also supported the legitimacy of the women’s movement.

Despite support by reformist ulama and members of the parliament, the so-called dowlat-e mehrvarzi–the kind and generous government–of Ahmadinejad has responded with harsh measures. At the time of this writing, the authorities have blocked the site of the One Million Signature Campaign eight times. Many of the activists have been detained on charges of “spreading propaganda against the system” and “acting against national security” while gathering signatures in public spaces. In 2008, two members of the campaign who were directly in charge of the websites, Zanestan.com [no longer online] and we-4change.info [domain name changed to we-change.org]–Maryam Hosseinkhah and Jelveh Javaheri respectively–were held in Evin prison on the above-mentioned charges. In November 2007, Ronak Safarzadeh and Hana Abdi, active members of the Campaign in Kurdestan province, were detained and held without charge or trial in Sanandaj by local officials from the Ministry of Intelligence. [Updates: Safarzadeh http://www.rahana.org/prisoners-en/?p=1497 and Abdi: http://www.amnesty.org.au/svaw/comments/20526/]

Arrests Target the Young

Most of the activists arrested in relation to the One Million Signature Campaign are in their twenties, too young to have witnessed the events leading up to the revolution or, in most cases, the revolution itself. For instance, Jelveh Javehri is 24 years old, a graduate student in sociology at Al-Zahra University who lost two of her brothers in the Iran-Iraq War. She is one of the many citizen journalists/bloggers who have directly contributed to broad coverage of the campaign on the Internet. Her arrest prompted Asieh Amini, another activist, to condemn the harsh response of the system as a violation of the commitment of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the World Summit on the Information Society, which obligates Iran to ensure “an open, inclusive information society that benefits all people.” (30)

Mothers for Peace

The nonviolent conflict sparked by the One Million Signature Campaign seems to have had a domino effect. The mothers of the young activists now in detention or condemned to receive lashings, along with others concerned about the prospects of war, have gathered to form Mothers for Peace (http://www.motherspeace.blogfa.com/). Another campaign by civil-society activists has also started, in conjunction with a signature campaign to stop stoning in Iran. As of December 16, 2007, this campaign had become an international movement by joining forces with activists from other Islamic countries. (31)

THE PROMISE OF THE INTERNET

This paper attempts to explain the public origins and deployment of information technology in Iran and its utilization by two forces in today’s Iranian society, directly challenging the political system. Iran has a nascent civil society or, to use Jeffrey Alexander’s words, “a civil sphere: a world of values and institutions that generate the capacity for social criticism and democratic integration at the same time.” (32) Among the challenges faced by the idea of an Islamic civil sphere are the sociopolitical critiques emanating from the reformist ulama and women. These movements oppose the current political structure in Iran with its unelected supreme leader at the top and an ultra-conservative president. In the absence of viable alternative political parties, these movements create civil power through direct participation or the Internet to broaden the civil sphere. If the political system is not able to incorporate their demands, it will be forced to change in fundamental ways.

On the surface, the reformist clerics and women’s-rights activists seem to be very far from each other in terms of their ideals and strategies. But a closer look at these movements reveals otherwise. The ulama, as well as women’s-rights activists, demand the fulfillment of their particular interests (eliminating the velayat-e faqih and discriminatory laws against women, respectively), while simultaneously calling for a radically different idea of Islamic justice. While the former is highly centralized, as religious movements traditionally have been in Iran, the latter is decentralized and participatory. Both movements, however, use the Internet to spread their ideas, recruit new members and attract international attention. Despite the regime’s crackdown and blocking of the activists’ sites, these reformers have shown resilience, and their new communicative strategies suggest ways to broaden the civil sphere in the service of democracy.

References

(1) See Jeffrey C. Alexander, The Civil Sphere (Oxford University Press, 2006).

(2) For a study of reform debate led by the ulama, see Said Arjomand, “The Reform Movement and the Debate on Modernity and Tradition in Contemporary Iran,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 34 (2002), pp. 719-31; Mehran Kamrava, “Iranian Shiism under Debate,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Summer 2003), pp. 102-112; Ali Gheissari and Vali Nasr, “Iran’s Democracy Debate,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Summer 2004), pp. 94-106; and Ziba Mir-Hosseini, “Rethinking Gender: Discussions with Ulama in Iran,” Critique, Vol.13 (Fall 1998), pp. 45-60.

</a(3) For a general introduction to Twelver Shii (Ithna Ashari) eschatology, see Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi’i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shi’ism (Yale University Press, 1985).

</a(4) See Mongol Bayat, Iran’s First Revolution: Shi’ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1909 (Oxford University Press, 1991).

(5) The other notable clerics who opposed Khomeini were Muhammad Reza Golpayegani, Mohamamd Rowhani, Reza Sadr and Hassan Qommi.

(6) The most important of these publications was Iman va Azadi (Faith and Freedom, Tehran: Tarh-e No; 1379/2000) by Mohamad Mojtaba Shabestari and Nazariyeh-haye Dowlat dar Feqh-e Shia (Perspectives on Government in Shia Theology, Tehran: Ney, 1377/1998) by Mohsen Kadivar.

(7) For a study of Internet politics in post-revolutionary Iran, see Babak Rahimi, “The Politics of the Internet in Iran,” in Mehdi Semati, ed., Media, Culture and Society in Iran: Living with Globalization and the Islamic State (Routledge, 2007), pp. 23-34; Nasrin Alavi, We Are Iran: The Persian Blogs (Soft Skull Press, 2005) and Liora Hendelman-Baavur, “Promises and Perils of Weblogistan: Online Personal Journals and the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Middle East Review of International Affairs, Volume 11, No.2, Article 6/8 (June 2007).

(8) Telegraph was used by the pro-constitutionalists to send political messages and information abroad, and cassette tapes were used to record and disseminate major speeches by revolutionary figures like Ali Shariati or Ayatollah Khomeini throughout the 1970s.

(9) These sites included the weblogs of Khatami’s vice president, Masoumeh Ebtekar http:// greenebtekar.persianblog.ir/and his advisor, Mohammad Ali Abtahi http://www.webneveshteha.com/en/ weblog/?id=2146307410.

(10) For Khatami’s website, see http://www.khatami.ir/. Nateq-e Nori’s former website address is http://nategh.co.ir.

(11) Montazeri’s objection to the Islamic Republic began to surface in the early years of the revolution, while he was a major figure in the regime. His critique of the government continued when he called for a more open polity and the institutionalization of political parties, which he believed were central to the original ideals of the Islamic revolution. Montazeri’s political fate was finally sealed when Khomeini forced him out of his position on March 28, 1989. Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani, the former first speaker of the parliament (Majlis), also drove a wedge between Khomeini and Montazeri. See Bahman Baktiari, Parliamentary Politics in Revolutionary Iran: The Institutionalization of Factional Politics (University Press of Florida, 1996), pp. 136-138, 171.

(12) This is according to an article in the statement and opinion section of his website, Pasokh-e Ayatollah Al-Ozma Montazeri be Chand Porsesh.

(13) For Sistani’s pro-democracy views, see Juan Cole, The Ayatollahs and Democracy in Contemporary Iraq (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, ISIM papers, 2006); Vali Nasr, The Shia Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future (Norton: 2006), especially pp. 172-78 and 189-190; Yitzhak Nakash, Reaching for Power: The Shi’i in the Modern Arab World (Princeton University Press, 2006) and Babak Rahimi, “Ayatollah Sistani and the Democratization of Post-Ba’athist Iraq,” United States Institute of Peace, Special Report 187 (June 2007).

(14) Mehdi Khalaji, “The Last Marja: Sistani and the End of Traditional Religious Authority in Shiism,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policy Focus No. 59 (September 2006), p. 9.

(15) This was not always the case. Prior to 2003, Khameini refused to recognize Sistani as a leading Shii scholar. See “Iran and Lebanon after Khomeini,” by H.E. Chehabi, in Distant Relations: Iran and Lebanon in the Last 500 Years, edited by H.E. Chehabi (I.B. Tauris, 2006), p. 299.

(16) One of the most interesting features of the footage are the images of people using mobile video and camcorders to record the incident. See http://www.youtube.com/ results?search_query=ayatollah%20boroujerdi&search=Search&sa=X&oi=spell& resnum=0&spell=1.

(17) Interview with a follower of Boroujerdi, November 8, 2007.

(18) For a general history of the Iranian women’s movement since the revolution, see Women and the Political Process in Twentieth Century Iran, by Parvin Paidar (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

(19) See “Feminism in an Islamic Republic: ‘Years of Hardship, Years of Growth,'” by Afsaneh Najmabadi, in Islam, Gender and Social Change, edited by Yvonne Y. Haddad and John L. Esposito (Oxford University press, 1998) pp. 59-85.

(20) For an up-to-date account of factional politics in Iran, see Mehran Kamrava, “Iranian National-Security Debates: Factionalism and Lost Opportunities,” Middle East Policy, Vol. XIV, No.2 (Summer 2007).

(21) Mohammad Khatami, Name-ye baraye Farda (A Letter for Tomorrow, Moassesseh-e Khaneh-e Farhang-e Khatami, 1383/2004).

(22) Nooshin Tarighi, “Men’s Race to Gain Women’s Votes,” Zanan, No. 121, Khordad 1384/June 2005, p. 2.

(23) Markaz Strategic Sepah (Center for Sepah’s Strategy) publicly announced that women’s-rights activists, along with other activists, pose a threat to Iran’s national security at a time of increasing tension with the United States (see: http://www.irwomen.net/spip.php?article4904).

(24) Shirin Afshar, “Everybody Condemned Violence: A Report of Women’s Demonstration on 22 Khordad,” with pictures posted on ISNA (www.isna.ir), Advarnews (advarnews.com) and Kosoof (www.kosoof.com) in Zanan, No. 133, Tir 1385/August 2006, p. 12-17.

(25) His arrest sparked international outrage by human-rights organizations around the world. See: http://action.humanrightsfirst.org/ct/M722_KnlGPJY/. Akbar Ganji, a human-rights activist, investigative journalist and former prisoner of conscience who was feed after 2,222 days of imprisonment, called for a hunger strike in front of United Nations Headquarters in New York on July 15, 2006, to free Musavi Khoini and others.

(26) Arzoo Osanloo, “Islamico-Civil Rights Talk: Women, Subjectivity and Law in Iranian Family Court,” American Ethnologist, Vol. 33, No. 2, (2006) pp. 191-209.

(27) The complete document can be found at: http://www.we-4change.info/ spip.php?article11.

(28) http://www.we-4change.info/spip.php?article662.

(29) http://www.we-4change.info/spip.php?article1310.

(30) See Asieh Amini’s blog: http://varesh.blogfa.com/post-587.aspx. For more information about WSIS, see http://www.itu.int/wsis/geneva/newsroom/press_releases/wsisopen.html.

(31) For more information, see http://www.meydaan.com/english/ wwShow.aspx?wwid=548.

(32) Alexander, The Civil Sphere, p. 4.

Dr. Rahimi is assistant professor of Iranian and Islamic studies at the University of California, San Diego. Ms Gheytanchi is an associate faculty of sociology at Santa Monica College. This piece was originally published in “Middle East Policy. 2008.”