The Death of the “Twitter Revolution” and the Struggle over Internet Narratives

March 15, 2011The death of the “twitter revolution” and the struggle over internet narratives

March 17, 2011

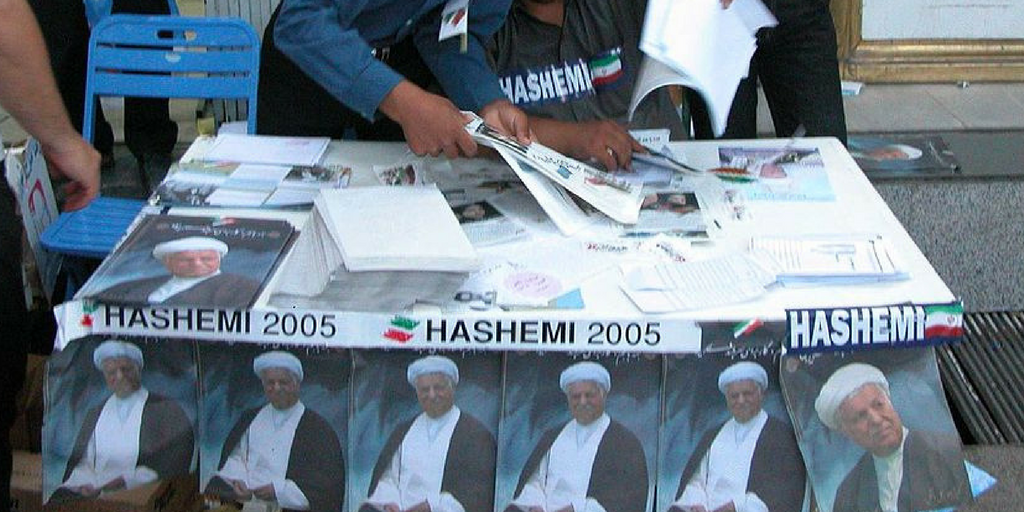

Indiscernible Phase: The Case of Sistani

The victory of Ahmadinejad in the 2005 presidential election marked a clear and present danger for the reformist ulama and the future of their online political activism. The increase in censorship by the hardline regime–radical politicians who aimed to resurrect the revolutionary zeal of the early 1980s–was bound to affect the ways in which political dissent could be expressed online. But, while the hardliners held a tight grip on the public sphere through the conservative legal machinery, the 2003 toppling of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime in Iraq by U.S.-led forces heralded a new era of reformist-ulama opposition. With Saddam gone from Iraq, these ulama found a fresh ally in their battle against the conservatives: the Najaf-based Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, whose scholarly credentials surpassed those of the entire clerical establishment in Iran.

The rise of Ayatollah Sistani as the most recognizable senior Shii cleric signaled a revival of traditional Shiism in Iraq that resonated with the ideas of the reformist clerics in Iran. An avid supporter of popular sovereignty and a follower of the pro-democracy clerics of the Constitutional Revolution (1906-11), Sistani was able to put into practice in Iraq many of the arguments the reformists made against the conservative, pro-Khomeini clerics in Iran. (13) His call for a popularly elected council to draft a constitution in November 2003 and for general elections in 2004, aimed at immediately empowering ordinary Iraqis, served as a powerful challenge to Khomeini’s vision of absolutist theocracy.

Sistani’s ascendancy expanded his religious network as well as its financial center, based in the Iranian city of Qom. With a growing annual income of more than $500 million a year, largely gained through religious taxes, his network is rapidly becoming an important force in the transnational Shii community, vying with Khamenei’s in Tehran. (14) Sistani’s expanding network includes the use of information technology operating through computer training centers where Internet use is taught and encouraged among his followers, students and representatives.

Sistani’s Aalulbayat Global Information and Media Center

Sistani’s Aalulbayat Global Information and Media Center hosts the most technologically advanced computer center in Qom, which since 1996 has provided one of the most significant religious websites in the Shii world: www.al-shia.com. It includes Sistani’s personal website, www.Sistani.com, where he offers the faithful his views on issues from religion to politics and current affairs. The center is also a hub for various websites dedicated to spreading the views of more than 50 high-ranking clerics, mostly reformist ulama who include senior figures like Montazeri until his death and Yosuf Sanei. For the most part, the Internet has increased the size and prestige of Sistani’s religious organization in Iran and worldwide.

In 2003, when Sistani’s authority grew because of his popularity in Iran after the fall of Saddam, the center presented the reformist Iranian clerics with a huge opportunity: the chance to further expand their Internet accessibility and express their views online. But this time, they were able to do so under the guise of Sistani’s religious teachings, which implicitly contradicted Khamenei’s religious authority and, consequently, his political power. In matters of religious concern, the reformist clerics were able to challenge Khamenei’s authority by publicly announcing their allegiance to Sistani as the most learned Shii scholar and the most widely followed source of spiritual imitation (marja taqlid). This signaled a major act of resistance from clerics who had been seeking to decentralize the Shii clerical institution and release it from the tight grip of Tehran since 1979.

A Delicate Rivalry

The reaction of the conservative clerics has been less open. Not only is Sistani a major religious figure; he is also highly popular among the Shiis in the region, especially in Iraq and Lebanon, where Iran has vital interests. (15) Sistani, too, has been careful not to upset the conservative clerics in Iran, since many of his seminaries, as well as his financial center, are based in Qom. But he is independent enough not to appease the Iranian regime by indirectly challenging Khamenei’s authority in religious matters, though these confrontations have occurred in subtle ways. Nevertheless, this delicate rivalry between the two religious authorities has provided an opportunity for a camouflaged dissent. This may not have any major consequences in the short term, but down the line it could pose serious challenges to the religious legitimacy of the Islamic Republic.

Yet the confrontational form of clerical resistance continues to be a force in the political landscape of Iran. The October 2006 arrest of Ayatollah Hussain Kazemeini Boroujerdi is a case in point. Since the early 1990s, Boroujerdi’s criticism of Khamenei and his increasing appeal among the religious sections of the Iranian population has posed a major threat to the authorities. It was no surprise that his arrest led to a number of public demonstrations, which were harshly put down by the state. An intriguing phenomenon followed Boroujerdi’s arrest: his followers recorded their clashes with the police and posted the footage on YouTube. (16) Although the YouTube site is blocked in Iran, Boroujerdi’s computer-savvy followers managed to email the recording to the ayatollah’s followers abroad so they would be able to post it online. (17) Iranian viewers were able to see the video by using various antifilter programs to access the site. The use of email and mobile phones was crucial for the way Boroujerdi’s followers communicated beyond the supervision of the authorities to attract international sympathy for their cause. As the case of Boroujerdi shows, the use of information technology carries the potential for a form of dissent that could unleash a new phase in the conflict between reformist and conservative clerics.