The Death of the “Twitter Revolution” and the Struggle over Internet Narratives

March 15, 2011The death of the “twitter revolution” and the struggle over internet narratives

March 17, 2011WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Since the end of the eight-year Iran-Iraq War, women’s-rights activists have started a slow but persistent movement for equality. During the reconstruction era, Iranian women gained a substantial presence in the workforce and demanded parity. (18) Many women’s publications, such as Zanan, (19) Zan, and Farzaneh, as well as governmental offices, started working on women’s issues. As the reform movement surfaced in the country, many women’s-rights activists joined forces with reformists, who could not have won the elections in 1997 without overwhelming support from Iranian women. As the reformists experienced backlash from the hardliners, specifically the judiciary, many reformist publications, including women’s publications and those sympathetic with their cause, were shut down. In the absence of political-party competition, women’s-rights activists used the Internet to express dissent and attract international attention.

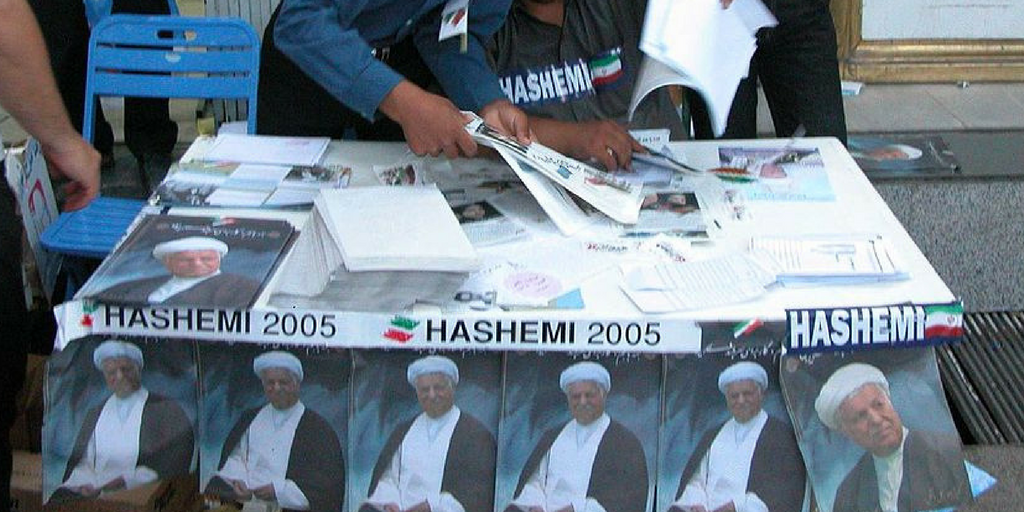

The 2005 elections in Iran showed the uncertainties of politics, (20) but it was also a historic time for women’s-rights activists to claim their independence from political factions. With only 60 percent of eligible voters going to the polls–as many boycotted the elections to protest the Guardian Council’s eligibility process–the reformists candidates Moin and Karrubi were defeated. Rafsanjani and Ahmadinejad earned 21 percent and 19.5 percent of the votes, respectively. In the midst of the second round of elections, the women’s-rights activists organized a peaceful protest on 22 Khordad 1384 (June 12, 2005) in front of the University of Tehran.

2005 Women’s Rights Demonstration

The demonstration announced an independent women’s-rights movement that once again targeted the constitution and the inequalities embedded in the Iranian legal system as obstacles to social justice. The Feminist Tribune, the activists’ website, which is no longer online, posted photos of the relatively calm event. The site was later blocked in Iran.

From the start, the women’s-rights demonstrations called on student activists and others to form a coalition. Women’s nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) from Kurdistan, Azerbaijan (the city of Tabriz), Esfahan and other provinces announced their full-fledged support. Within days, 1,000 people had signed the public declaration, also posted online, calling upon the Iranian state to change discriminatory laws with regard to women. More than 130 weblogs posted their call to action, and many women’s-rights groups in the United States and Europe endorsed the action.

The demonstration in 2005 drew more than 6,000 people, but the state-run news agencies reported only 700. While the opinion polling stayed uneventful, reflecting the boycott by many, the site of the demonstration attracted relative enthusiasm. At the heart of these activists’ efforts was a demand for amending the constitution to limit the future president’s powers to make fundamental political, economic and social changes. Instead of an apathetic boycott, the women’s-rights activists were able to show a political alternative: a nonviolent movement to change the current constitution, which allows the supreme leader and the unelected Guardian Council to approve and ultimately appoint the president of the country.

The Withering of Reform

With only seven candidates successfully vetted by the Guardian Council, conditions were ripe for an independent movement to remind the public of the inherent limitations of the Iranian constitution. After the experience of the reformist government of President Khatami (1997-2005), there was a general feeling of despair among Iranian activists who had previously placed much hope in the “civil society” project. In 2004, Khatami recognized that the reformist camp was withering away. In a tract entitled “A Letter for Tomorrow,” (21) he defended his record within the severe limitations placed on him by radical political factions and the constitution. While Ahmadinejad used the opportunity to win the support of the lower classes with his radical rhetoric, through online campaigns and carefully planned demonstrations, women’s-rights activists seized the moment to demand changes in the constitution that would render any reform effort obsolete.