The Death of the “Twitter Revolution” and the Struggle over Internet Narratives

March 15, 2011The death of the “twitter revolution” and the struggle over internet narratives

March 17, 2011References

(1) See Jeffrey C. Alexander, The Civil Sphere (Oxford University Press, 2006).

(2) For a study of reform debate led by the ulama, see Said Arjomand, “The Reform Movement and the Debate on Modernity and Tradition in Contemporary Iran,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 34 (2002), pp. 719-31; Mehran Kamrava, “Iranian Shiism under Debate,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Summer 2003), pp. 102-112; Ali Gheissari and Vali Nasr, “Iran’s Democracy Debate,” Middle East Policy, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Summer 2004), pp. 94-106; and Ziba Mir-Hosseini, “Rethinking Gender: Discussions with Ulama in Iran,” Critique, Vol.13 (Fall 1998), pp. 45-60.

</a(3) For a general introduction to Twelver Shii (Ithna Ashari) eschatology, see Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi’i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shi’ism (Yale University Press, 1985).

</a(4) See Mongol Bayat, Iran’s First Revolution: Shi’ism and the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1909 (Oxford University Press, 1991).

(5) The other notable clerics who opposed Khomeini were Muhammad Reza Golpayegani, Mohamamd Rowhani, Reza Sadr and Hassan Qommi.

(6) The most important of these publications was Iman va Azadi (Faith and Freedom, Tehran: Tarh-e No; 1379/2000) by Mohamad Mojtaba Shabestari and Nazariyeh-haye Dowlat dar Feqh-e Shia (Perspectives on Government in Shia Theology, Tehran: Ney, 1377/1998) by Mohsen Kadivar.

(7) For a study of Internet politics in post-revolutionary Iran, see Babak Rahimi, “The Politics of the Internet in Iran,” in Mehdi Semati, ed., Media, Culture and Society in Iran: Living with Globalization and the Islamic State (Routledge, 2007), pp. 23-34; Nasrin Alavi, We Are Iran: The Persian Blogs (Soft Skull Press, 2005) and Liora Hendelman-Baavur, “Promises and Perils of Weblogistan: Online Personal Journals and the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Middle East Review of International Affairs, Volume 11, No.2, Article 6/8 (June 2007).

(8) Telegraph was used by the pro-constitutionalists to send political messages and information abroad, and cassette tapes were used to record and disseminate major speeches by revolutionary figures like Ali Shariati or Ayatollah Khomeini throughout the 1970s.

(9) These sites included the weblogs of Khatami’s vice president, Masoumeh Ebtekar http:// greenebtekar.persianblog.ir/and his advisor, Mohammad Ali Abtahi http://www.webneveshteha.com/en/ weblog/?id=2146307410.

(10) For Khatami’s website, see http://www.khatami.ir/. Nateq-e Nori’s former website address is http://nategh.co.ir.

(11) Montazeri’s objection to the Islamic Republic began to surface in the early years of the revolution, while he was a major figure in the regime. His critique of the government continued when he called for a more open polity and the institutionalization of political parties, which he believed were central to the original ideals of the Islamic revolution. Montazeri’s political fate was finally sealed when Khomeini forced him out of his position on March 28, 1989. Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani, the former first speaker of the parliament (Majlis), also drove a wedge between Khomeini and Montazeri. See Bahman Baktiari, Parliamentary Politics in Revolutionary Iran: The Institutionalization of Factional Politics (University Press of Florida, 1996), pp. 136-138, 171.

(12) This is according to an article in the statement and opinion section of his website, Pasokh-e Ayatollah Al-Ozma Montazeri be Chand Porsesh.

(13) For Sistani’s pro-democracy views, see Juan Cole, The Ayatollahs and Democracy in Contemporary Iraq (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, ISIM papers, 2006); Vali Nasr, The Shia Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future (Norton: 2006), especially pp. 172-78 and 189-190; Yitzhak Nakash, Reaching for Power: The Shi’i in the Modern Arab World (Princeton University Press, 2006) and Babak Rahimi, “Ayatollah Sistani and the Democratization of Post-Ba’athist Iraq,” United States Institute of Peace, Special Report 187 (June 2007).

(14) Mehdi Khalaji, “The Last Marja: Sistani and the End of Traditional Religious Authority in Shiism,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policy Focus No. 59 (September 2006), p. 9.

(15) This was not always the case. Prior to 2003, Khameini refused to recognize Sistani as a leading Shii scholar. See “Iran and Lebanon after Khomeini,” by H.E. Chehabi, in Distant Relations: Iran and Lebanon in the Last 500 Years, edited by H.E. Chehabi (I.B. Tauris, 2006), p. 299.

(16) One of the most interesting features of the footage are the images of people using mobile video and camcorders to record the incident. See http://www.youtube.com/ results?search_query=ayatollah%20boroujerdi&search=Search&sa=X&oi=spell& resnum=0&spell=1.

(17) Interview with a follower of Boroujerdi, November 8, 2007.

(18) For a general history of the Iranian women’s movement since the revolution, see Women and the Political Process in Twentieth Century Iran, by Parvin Paidar (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

(19) See “Feminism in an Islamic Republic: ‘Years of Hardship, Years of Growth,'” by Afsaneh Najmabadi, in Islam, Gender and Social Change, edited by Yvonne Y. Haddad and John L. Esposito (Oxford University press, 1998) pp. 59-85.

(20) For an up-to-date account of factional politics in Iran, see Mehran Kamrava, “Iranian National-Security Debates: Factionalism and Lost Opportunities,” Middle East Policy, Vol. XIV, No.2 (Summer 2007).

(21) Mohammad Khatami, Name-ye baraye Farda (A Letter for Tomorrow, Moassesseh-e Khaneh-e Farhang-e Khatami, 1383/2004).

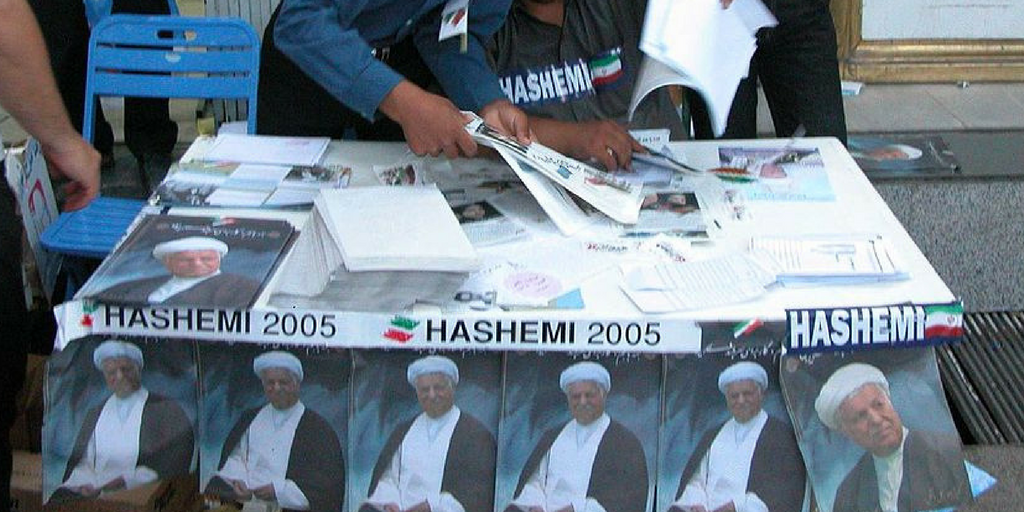

(22) Nooshin Tarighi, “Men’s Race to Gain Women’s Votes,” Zanan, No. 121, Khordad 1384/June 2005, p. 2.

(23) Markaz Strategic Sepah (Center for Sepah’s Strategy) publicly announced that women’s-rights activists, along with other activists, pose a threat to Iran’s national security at a time of increasing tension with the United States (see: http://www.irwomen.net/spip.php?article4904).

(24) Shirin Afshar, “Everybody Condemned Violence: A Report of Women’s Demonstration on 22 Khordad,” with pictures posted on ISNA (www.isna.ir), Advarnews (advarnews.com) and Kosoof (www.kosoof.com) in Zanan, No. 133, Tir 1385/August 2006, p. 12-17.

(25) His arrest sparked international outrage by human-rights organizations around the world. See: http://action.humanrightsfirst.org/ct/M722_KnlGPJY/. Akbar Ganji, a human-rights activist, investigative journalist and former prisoner of conscience who was feed after 2,222 days of imprisonment, called for a hunger strike in front of United Nations Headquarters in New York on July 15, 2006, to free Musavi Khoini and others.

(26) Arzoo Osanloo, “Islamico-Civil Rights Talk: Women, Subjectivity and Law in Iranian Family Court,” American Ethnologist, Vol. 33, No. 2, (2006) pp. 191-209.

(27) The complete document can be found at: http://www.we-4change.info/ spip.php?article11.

(28) http://www.we-4change.info/spip.php?article662.

(29) http://www.we-4change.info/spip.php?article1310.

(30) See Asieh Amini’s blog: http://varesh.blogfa.com/post-587.aspx. For more information about WSIS, see http://www.itu.int/wsis/geneva/newsroom/press_releases/wsisopen.html.

(31) For more information, see http://www.meydaan.com/english/ wwShow.aspx?wwid=548.

(32) Alexander, The Civil Sphere, p. 4.

Dr. Rahimi is assistant professor of Iranian and Islamic studies at the University of California, San Diego. Ms Gheytanchi is an associate faculty of sociology at Santa Monica College. This piece was originally published in “Middle East Policy. 2008.”