Let’s Beef Up and Meet Up

March 11, 2011

Iran’s reformists and activists: Internet exploiters

March 15, 2011The death of the “twitter revolution” and the struggle over internet narratives

In her latest speech on internet freedom, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared the internet the “town square” of the 21st century. Clinton seized on the widespread attention for Facebook during the Egyptian revolution and used the opportunity to reiterate internet-oriented US foreign policy. Just days earlier the Egyptian people had ousted Hosni Mubarak, their dictator of 30 years. Cairo’s Tahrir Square had been occupied by protesters, stained with the blood of the revolution’s martyrs, and gained iconic status as the center of the 21st century’s most populous revolutionary movement. Soon after, protesters in Libya named the Northern Court in Benghazi “Tahrir Square Two.” If these events show us anything, it is that the town square of the 21st century is still, simply, the town square.

Internet Hyperbolae

It is not the first time Clinton’s language has hyperbolized the role of the internet, thus making her appear severed from reality. Author and scholar, Eyvgeny Morozov, skillfully rebutted her first major speech on internet freedom given in January 2010 on these very grounds, expressing unease at the Cold War imagery she evoked in warnings that “a new information curtain is descending.” Clinton’s latest speech reminds us that the power struggle over new technologies is not limited to the battles over who uses and controls the internet and how. It includes the battles over who gets to define and frame the internet through dominant narratives, and who challenges them.

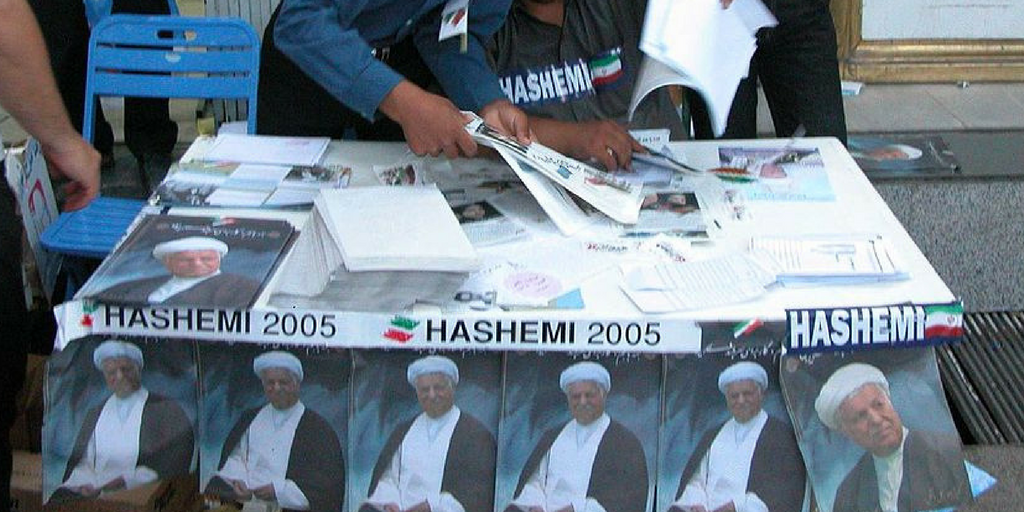

Perhaps the most widespread and heated contestation of an internet narrative is that of the “Twitter Revolution.” Although it was first used with reference to Moldova, this term enjoyed its peak during the tumultuous aftermath of the Iranian presidential elections of June 2009. With his piece, The Revolution will be Tweeted, Andrew Sullivan was quickly established as a leading proponent of the hype. He eagerly compared the power of the Iranian protesters to the electoral success of President Barack Obama the year prior. The only link seemed to be some broad associations with democratic change and popular associations with social media applications such as Twitter, Facebook, MySpace, and YouTube, but it certainly caught on.

Down with the “Twitter Revolution”!

Unfortunately, Sullivan not only jumped the gun on Iran, his perspective also obscured the ways the Obama campaign had effectively hijacked users’ online social networks, rather than building them, as documented in Eric Boehlert’s Bloggers on the Bus. Even though Iran’s case was still developing at the time, tech journalists, bloggers, activists, and independent/public news media immediately poked the “Twitter Revolution” narrative full of holes. These skeptics challenged the notion that technologies rather than people are decisive for social movements, and continue to argue for placing new media impacts within wider, offline (socio-economic and political) contexts, stressing that the new technologies are “tools” that are used for oppression as well as liberation.

Although Iran’s case carried the Twitter Revolution narrative to new heights, it also played a part in mainstreaming its counter-narratives. Sullivan himself was soon among those “cured” of the “Twitter obsession,” as Morozov put it. And notwithstanding the unfortunate irony about the “town square” metaphor, Clinton’s latest speech reflected elements of this more balanced counter-narrative when she said of Egypt and Tunisia:

People protested because of deep frustrations with the political and economic conditions of their lives. They stood and marched and chanted and the authorities tracked and blocked and arrested them. The internet did not do any of those things; people did. In both of these countries, the ways that citizens and the authorities used the internet reflected the power of connection technologies on the one hand as an accelerant of political, social, and economic change, and on the other hand as a means to stifle or extinguish that change… We realize that in order to be meaningful, online freedoms must carry over into real-world activism.”

Gone is the empowerment of technologies over people. Despite the contested “Twitter revolution” narrative’s partial revival through these recent revolutions, we all seem to be sobering up more and more from the new media celebrations. It looks like the counter-narrative has permeated the mainstream, balanced the scales, and even pronounced the debate around the “Twitter Revolution” dead.

What next?

Perhaps looking back on the rise of this particular narrative can shed some light on the path forward, including how to approach its more subtle but persistent variants such as “the Wikileaks Revolution” (Tunisia) and “Revolution 2.0” (Egypt). In Iran’s case, techno-utopianism in international coverage boomed due to foreign journalists being banned, credited Iranian journalists being restricted, and a young, mobile, tech-savvy, and highly educated population being at the ready. Certainly, the Western audience’s recognition of social media networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube as popular, Western, youth-oriented, and benign also played a part. But the “Twitter revolution” also caught on due to a number of narratives that, in the Western consciousness, pre-existed the uprising.

One of them was the idea, cultivated since the early 2000s, of Iranian dissident blogger-journalists being driven to the free spaces of the internet in regionally disproportionate numbers, and experiencing persecution for their online, anti-regime endeavors. The stories of persecuted bloggers like Sina Motallebi and Hossein Derakhshan (still in jail today) come to mind, as does that of Omid Reza Mir Sayafi, the first Iranian blogger to die in prison. In the same period, the Bush administration pushed the Iran Freedom Support Act, which was passed in September, 2006. The serendipitous overlap between the rise of the internet’s role in Iranian civil society and the US regime-change agenda seemed to strengthen both. An additional narrative, purportedly reproduced historically by Iranian diaspora in the West, was one of Iranians (or “Persians”, rather) as intellectually and culturally advanced, similar to Westerners, “civilized,” and proud.

But there was also a deeper story about the internet itself as a vehicle of genuine democratic change that may have tipped the scales from balanced online/offline international solidarity towards over-enthusiasm about internet technologies. Fred Turner’s From Counterculture to Cyberculture traces internet narratives from the technology’s beginnings, and shows that the intersection between the internet and visions of utopian societies is as old as the Net itself. Could this utopian genesis narrative be at the root of today’s internet-boosting?

“Tools of liberation”

Turner argues that early perceptions about computers and the internet were shaped less by the engineers and programmers who made them and more by an elite of journalists and hippy ideologues from 1960s and 70s San Francisco who had the access and influence to write about these new technologies. This narrative was intended “to create the cultural conditions under which microcomputers and computer networks could be imagined as tools of liberation.” Given Turner’s account, it is not hard to see how today’s internet conjures up images of a quest for freedom.

This could be the reason why, in the summer of 2009, San Franciscan computer programmer, Austin Heap, was moved to involve himself in the Iranian Green movement without any prior knowledge or interest in Iran. He designed Haystack, a program which encrypts all online activity and hides this encrypted data in what looks like normal traffic. Heap’s inspiration was seeing images from the protests – his only connection to what he saw, the internet. The Tor Project was a program similarly used in solidarity with Iranians. Tor is headed by Andrew Lewman and designed to allow people in Iran to use anonymous proxies to hide their identities and online activity. The attention for such stories boomed and overshadowed the Iranian government’s censorship, government supporters’ hacking of opposition websites, and the government’s use of online amateur footage to identify protesters.

In addition, the hacktivist groups Anonymous and Pirate Bay supported the protesting Iranians by starting the website, Anonymous Iran, providing tools to circumvent censorship by way of navigating with privacy, uploading files through the Iranian firewall, and launching attacks on pro-government websites. The international involvement and dedication of these cyber-activists further entwined utopian internet narratives with the message of the Iranian pro-democratic movement, especially as they coalesced with the Green protesters’ counterparts outside the country.

Between solidarity and “Statecraft”

But these acts of solidarity also smuggle in elements of US foreign policy and commerce, together with a touch of American nationalism. Through international solidarity actions, the lines between the interests of citizens, business, and the state have become dangerously blurred, for instance, with the US administration’s “21st Century Statecraft”, spearheaded by none other than Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton (yes, she likes reminding us which century it is). The US government connections to solidarity actions with Iran first came under public scrutiny in the much-covered delay in Twitter maintenance when the Iran protests were breaking out in June 2009.

The US State Department asked the private company to instate a maintenance delay so that Iranians could continue to use Twitter at Iran’s peak traffic hours (the company denied that the State Department had a hand in their decision to delay maintenance). State connections are also rife around Tor, as the project was an existing one, funded by the US Department of Defense (but also other organizations like the Electronic Frontier Foundation). More state links emerged on April 13th 2010, when the US Treasury Department gave Heap an exemption from US sanctions to distribute Haystack legally in Iran.

This was part of a wider policy approach that saw a ban lifted on US companies like Google and Microsoft to export their products to Iran in March of the same year under the assumption that this would facilitate the development of Iranian civil society. But this would have little if any effect for Iranian citizens who would likely already be accessing these programs illegally. In Heap’s case, the Haystack project fizzled out quietly as it was later found to be fraught with security holes, thus endangering the very people it was meant to protect.

But while rushing to criticize this US narrative of “democratizing internet diplomacy,” and embracing post-Twitter revolution perspectives, some have ended up highlighting the spirit of American free market entrepreneurship that drives the technology industry that gave birth to the internet as we now know it. When American business competes with government to implicitly take credit for people’s revolutions we are still a far cry from being moved by the power of universal values of humanity. This blatant self-congratulation reminds us that the Twitter revolution narrative is more about a clamoring to claim glory for our own principles, policies, and tools. As one critic declared, “To proclaim a Twitter revolution is almost a form of intellectual colonialism, stealthy and mildly delusional: We project our world, our values, and concerns onto theirs and we shouldn’t.”

Intervention hypocrisy

At any rate, the cracks in America’s hypocritical internet policies are now receiving increasing attention in ongoing public discussions around US internet policy, and the narrative is shifting in a new direction. Two major issues are dominating: Wikileaks and Net Neutrality. The Net Neutrality debate currently raging in the US involves defending internet access for users, not against despotic leaders but against big business interests.

The Obama administration came to power having promised to instate federal Net Neutrality laws to protect users from broadband operators blocking or prioritizing certain internet content, or charging content providers fees for favorable placement. Despite these claims, in December 2010, President Obama has allowed broadband companies like Google and Verizon to effectively write the FCC regulatory policy meant to protect internet users. Some critics have even made comparisons between the total suppression of the internet during the Egyptian uprising and the damages done by weak Net Neutrality laws.

And questions around US hypocrisy as revealed by its response to Wikileaks have certainly gained much attention internationally. Secretary Clinton made sure to address it in her latest policy speech, bringing up and defending the administration’s condemnation of the Wikileaks organization, which used the internet to widely distribute tens of thousands of leaked documents, including secret diplomatic cables. Since then, what is seen by some as an international manhunt launched by the US government for dissident Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, has raised questions about the US discourse of democracy and freedom of speech in its policy regarding the internet. And this does not even touch on the quieter issue of America’s surveillance of its own citizens though Facebook.

Controlling information dissemination according to political interest and using media as a means of foreign intervention, are not new – certainly not to the US. The issue raises comparisons to the US Federal government’s Cold War use of the external Voice of America radio and TV broadcasts in an anti-Soviet “campaign of truth.” The role of VOA (an organization that also provided funding for the Tor Project) remains problematic today, including in the case of Iran where it is available via satellite and internet despite being banned by the Islamic Republic, and receives criticism on various fronts both inside and outside Iran.

The narrative of hypocritical interventions challenges the US narrative of internet diplomacy, and must be seen within the context of wider US foreign policy. As Morozov put it, “You cannot say, ‘We want to promote internet freedom,’ when every single other branch of the US government wants to promote the opposite.” So, what is new about (the US) using the internet along these same, old lines?

Is the internet any different?

It is hard to say whether America’s present internet intervention policies are a deterrent from, or an aperture to, sanctions and/or military action against Iran. Some American progressives denounced the Iran Freedom Act as “laying the groundwork for war.” But since 2009, some blogger activists in Iran, as well as Iranian American analyst Abbas Milani at Stanford University, have called for stronger US action in further facilitating internet access in Iran. It remains to be seen whether US investment and/policy in this vein has any direct influence for civil society inside Iran. However, what is clear are the difficulties that international money has brought upon Iranian NGOs in the past, having had the assistance deemed as “foreign intervention” by the Islamic Republic.

But, surely, precisely any elements that make controlling the internet difficult for authoritarian regimes also make it difficult to use as a targeted tool of intervention. Its many-to-many (versus broadcast’s one-to-many) capability for distributing content is one such quality, making the internet’s relatively speedy, low-cost, and large-scale interactive potentials too unruly for a single top-down truth campaign. This also makes it impossible for all international online involvement in Iran’s social movements or civil society to be reduced to simply instances of foreign interference.

As in Tunisia and Egypt, a multiplicity of international support was shown to Iranian protesters through, and because of, internet communications. Whether through the proxy servers offered, the DDoS attacks carried out on regime websites, or simply the widespread and timely sharing of protest footage on Facebook and Twitter outside the country. Whether through individuals or organizations, government or non-government funded sources, the variety of direct support reflected a difference from what broadcast media were capable of offering in many ways.

Just one of these was the circulation of protest footage that was combined with a soundtrack and, sometimes, photographic stills. As the original protest footage circulated online it quickly became adapted, built-upon, and developed into what can be called a genre of its own: the first interactive, multimedia montages of revolution to be circulated to a wide audience while the event itself is still unfolding. These mash-up products not only mobilize networks of emotional empathy, but the process of their production itself allows a network of people to add value through their creative alterations. This value is added even in the simple act of adding a personal subscript to the shared footage by taking up the invitation to “say something about this link.”

What’s in a medium?

Media scholar, Marshal McLuhan’s seminal claim is that the medium always embeds itself within the message it conveys. Indeed, McLuhan’s idea(l) of the “global village” directly inspired the San Franciscan, hippy internet boosters and has since become firmly entrenched in many common views of the internet today. Utopian societies aside, if we want to understand how narratives about internet technologies and applications play a part in struggles over the internet, we are well-served to take seriously the question of how the medium influences the message.

This question tends to be left unaddressed by the staunchest internet skeptics. Seemingly satisfied with beating the (mostly-) dead horse of the Twitter Revolution, they emphasize that new media do not have all that much new to offer. Bestselling author, Malcolm Gladwell’s much-cited piece, Small Change: Why the Revolution will not be Tweeted, placed him squarely in the counter-hype camp. To him, the medium of communication is rather irrelevant to the message communicated, but he prefers good-old-fashioned face-to-face, shoulder-to-shoulder activism. He reapplies this view in his recent comment on the Egyptian revolution, stating that the “strong ties” (as opposed to “weak ties”) necessary for the centralization and leadership that lead to effective activism and meaningful social change are not built via the internet.

Let us leave aside the poignant critique that points out Gladwell’s romanticization of activism and oversight of key combinations of weak and strong ties necessary for social change. Instead, returning to Turner’s study, let us recall a shift that took place with emergence of the internet from the 1950s Cold War notion of computers as machines of heartless State bureaucracy and interests, to the 60s’ countercultural movements. Inspired and fascinated by the structure of this new technology, ideologues like Howard Rheingold, helped reinvision computer users as a networked “virtual community,” intentionally framed in contrast to the centralization of the state. It also served the purpose of disconnecting the narrative of this new media from the US military project it started out as.

It seems Gladwell’s rejection of the internet’s power rests on his implicit acceptance of that original narrative: that the decentralized and non-hierarchical structure of technology itself leads to a decentralized and non-hierarchical structure of the social movements it is used in. But it is not entirely clear why this would necessarily be the case.

Winning the struggle over internet narratives

We see the power of narratives in the ways we think about, talk about, and envision the role of the internet in our everyday lives and societies –- present and future . We also see the importance of challenging dominant narratives about the internet when they are hyperbolic, misrepresentative of actual cases of internet use, and disempowering to people. We have seen activists and tech reporters challenge and bury the Twitter Revolution (and its ghosts in the case of Tunisia and Egypt).

In parallel, journalists have strongly challenged the notion that the internet makes professional journalism obsolete, and organizers have challenged the notion that using the internet removes any possibility for leadership in mobilization. Wikileaks’ Assange has repeatedly said that simply making information available in the form of raw data online is not enough, teaching us that certain designated centers must make information relatable, urgent, and politicized.

And columnist Roger Cohen, who extensively covered the Green Movement, has stated repeatedly that in an information-rich world, fast-paced and emotionally moving scenes or accounts circulate widely, which makes the role of credited journalists all the more important as storytellers, “contextualizers,” analysts, and verifiers. And the Egyptian revolution has shown us that collectives such as youth and student groups, organized labor, leftist organizations, etc. are key in leading revolutionary process all the way. Their effective use of online applications in mobilization has brought forth a form of leadership with multiple, dynamic nodes rather than an absence of them.

And in both Iranian and Egyptian cases we see that social media as information disseminators are first on the scene, ahead of the news, and post unique content, but still require the eventual boost of established broadcast media (CNN, Al Jazeera, etc.) to make the story pass the threshold into the global. As some announce our entry into a stage of cyber-pragmatism rather than hyperbolism, we see the significance of highlighting critical counter-narratives wherever signs of techno-utopianisms, hypocrisies of the powerful, and national and market chauvinisms reemerge.

Looking at Iran

While the prevalence of internet usage in Iran was cited as a reason for the popular uprising in 2009, the current revolutionary wave engulfing Arab nations flies in the face of that story. The question is – as the lingering techno-utopian, Clay Shirky himself admits – if the internet is so indispensable for social movements, should Iran’s technological and educational advantages relative to regional counterparts not have meant certain success? Rather, the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions revealed by contrast that Iran’s Green Movement seems to have come to a point of relative stagnation.

But this has little if anything to do with whether or not social media are being used (effectively), and everything to do with the differences between Iran and its co-regionals; e.g. the reformist leadership, the composition of the movement, the structure and power of the state, existing support for the establishment, relationship to the West, the people’s past experience with revolution, the demands of protesters, and their links to organized labor, etc. Developing our own narratives of the internet based in hypotheses drawn from experiences (for example the proposed blackout-protest hypothesis) is an integral part of the power struggle over new media and internet technologies.

Looking at how people not only use, but perceive the internet and how these perceptions are shaped by certain media narratives, will bring us closer to grasping the internet’s (potential) power in social movements, civil society, and democratic change. We also need to take seriously the impact that new media have on people’s experiences, interpretations, and reactions to the messages they consume through it, acknowledging the new possibilities, genres, and relationships taking shape.

Older media have played important roles in social movements in the past; the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran was significantly facilitated by cassette tapes circulated subversively among the people. However, it was never asserted as a “Cassette Tape Revolution,” protesters did not hold up signs and banners thanking their tape players, and graffiti of tapes did not adorn Tehran walls; as far as I know, nor did that of cellphones or email in the recent revolts. How can we understand this if not as evidence of our changing relationships with new media through emerging and dynamic narratives?