Iran’s Reformists and Activists: Internet Exploiters

March 29, 2011

Iran: Independent Civil Society Organizations facing obliteration

April 5, 2011Berlin, Bam, New Media, and Transnational Networks

by Halleh Ghorashi and Kees Boersma

The diaspora gap

Many Iranians inside Iran have struggled to improve their positions within the limiting space of the Islamic Republic. In the 1990s, this resulted in the formation of a limited form of civil society within the context of the political reformist movement in Iran. At that time, many NGOs began a struggle to become independent of the state. Activists began to claim, although not without fear, as much space as possible for expressing ideas. Despite the changes inside Iran, the gap between Iranians inside and outside remained wide in the 1990s. On the one hand, the diaspora’s memory of the repressive situation in Iran made them suspicious of any kind of activism from within the country. On the other, Iranian activists inside the country felt ignored and distrusted the judgement of those living in the diaspora, believing that this group had been gone too long and was too far away to know the true situation. This mutual distance and distrust hindered contacts.

Transnational networks create a sense of (virtual) belonging

Transnational, virtual networks of Iranians outside Iran created a new space for many as well as enabling the creation of a virtual sense of belonging with others. The virtual spaces were initially seen primarily as safe places to make connections; later there was increased interaction between members of the diaspora and those inside Iran. The use of the Internet enabled many to cross community borders that had seemed completely closed for years.

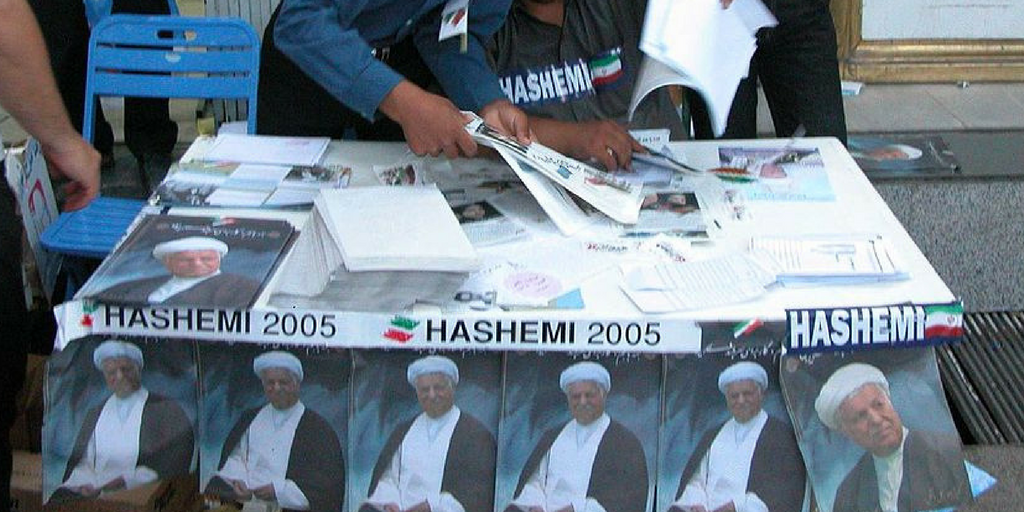

A change in the political climate in Iran, beginning in the mid 1990s, combined with the growth of the reformist movement there, further stimulated the development of transnational contacts between many Iranians inside and outside Iran. The image of a completely repressive regime was eroding among a significant group within the Iranian diaspora. They acknowledged that the sense of oppression varied among different groups. This growing differentiation of experiences towards Iran led to increasing transnational online and offline exchanges, causing a change of identity patterns within the diaspora and leading first to a less exclusive attitude towards Iranians in Iran and then to a rising number of activities and networks with Iran.

Emerging civil society in Iran

An early sign of change was an increased openness towards activists inside Iran and an acceptance of the possibility of NGOs within the country, which would have been unimaginable in the 1980s. Another sign was the realization that the Iranian diaspora was not homogeneous in its views of Iran. This seemed to be true even for the groups that were considered to share the same view, such as Iranian leftists in exile. Different groups of politically oriented Iranians all over the world started to clash with each other over their different views of the situation in Iran.

2000 Berlin Conference

One such clash occurred at the 2000 Berlin conference. In April that year, the Heinrich Boll Foundation and the Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt in Berlin organized the conference ‘Iran after Elections’ on civil society and the reform process in Iran. The aim of the conference was to bring Iranian intellectuals, politicians, and artists from inside and outside Iran together to review the latest developments in the country. The conference was disrupted by heckling, which prevented many participants from speaking. This was followed by other political actions including a striptease performed by a woman and a man, which was repeatedly shown on national television in Iran and spread throughout the world via the Internet. The conservatives in power in Iran used this incident to demonstrate that Islam and the Islamic Republic had been insulted during the conference.

Revolutionary court trials for participants

Among the participants of the conference from Iran were the human rights activist and lawyer Mehrangiz Kar, journalist, and the editor of Zanan, Shahla Sherkat, outspoken reformist cleric Hojatoleslam Hasan Yusefi-Eshkevari, who was the elected MP (of the sixth parliament) from Tehran, journalist Jamileh Kadivar, journalist and researcher Akbar Ganji, publisher and human rights activist Shahla Lahiji, in addition to the famous writers Mahmoud Dolatabadi and Mohammad Ali Sepanlou.[1] Upon their return to Iran, a revolutionary court in Tehran tried these activist participants for attending the conference. Many were sentenced to several years in prison. Iranian activists who had been risking their lives in Iran were thus attacked both by a number of Iranian ‘radical leftist’ activists living in diaspora and by the conservative powers in Iran.

An end to nostalgia and an investment in real connections

The painful events of the conference became the focus of online and offline discussions inside and outside Iran, a major talking point on the Internet and in formal and informal gatherings in the US and in Europe. Online and offline discussions were used interchangeably to air views related to Iran and the space for activism in Iran. Some factions began re-evaluating their previous positions. More and more Iranians outside Iran started to distance themselves from a nostalgic connection to the past and to invest in connections with other Iranians, in diaspora and in Iran, which were based on shared interests and activities. The initial exilic identity, with its rooted notion of a home left behind, was replaced by a more rhizomatic network-based diasporic approach to Iran as one basis of reference among many others.

Shifting identity: Opening of a new space

In December 2003, Shirin Ebadi, an Iranian woman lawyer and human rights activist, received the Nobel peace prize. In the same month, a horrifying earthquake shook the historical city of Bam and tens of thousands of people lost their lives. Both of these had a huge impact on Iranians both inside and outside Iran. While Shirin Ebadi’s prize became a source of joy and hope for the future for the majority of Iranians, the Bam earthquake left them feeling shocked and powerless. The involvement of a large group from the Iranian diaspora in both events — in the form of transnational activities with Iran — was significant. Millions of dollars were donated from the Iranian diaspora to Iran to help the survivors of Bam. Such a large transfer of money to Iran by members of the diaspora was unthinkable in the 1980s and even in the 1990s. Diaspora groups and individuals collaborated with groups and individuals in Iran to bring aid and reconstruction to the people of Bam and connections among them strengthened as a result.

Virtual diaspora connects to those inside Iran: Engaging in social and political change

The (virtual) diaspora became more and more interested in connecting to people and organizations inside Iran. This more inclusive attitude meant that parts of the diaspora not only accepted the existence of a civil society in Iran, but they also started to contribute to its strengthening. New transnational networks served as a bridge to connect large groups of Iranians worldwide to efforts to reconstruct their country of origin. In this way the content of transnational activities for many changed from exclusively political to more inclusive and with a humanitarian bent.

Reacting to the earthquake left little time for many members of the Iranian diaspora to ponder their involvement with Iran. After Bam, the transnational online and offline connections between the diaspora and Iran grew to a scale previously unknown. The earthquake made an increasing number within the Iranian diaspora realize that their contributions could make a difference inside the country. The events of December 2003 resulted in increased transnational connections and a much more intensive relationship between groups in the diaspora, certain Iranian NGOs, and many activists in Iran.

Changing Patterns, Increasing Activities

Virtual space was essential for the Iranian diasporas to initiate new transnational connections. This was especially important during the 1980s when the strict policing of the Iranian national border limited physical interactions. These virtual — and, later, increasingly physical — transnational interactions enabled novel forms of negotiation regarding the positioning of the diaspora towards Iran.

Iranian transnational virtual network

There can be little doubt that the Internet is one of the most effective means to mediate between Iranians living all over the world. The Iranian transnational virtual network has brought many lives and spaces together. This aspect of mediation has proven to be quite powerful in providing alternative spaces for interaction among Iranians worldwide by stretching the limiting boundaries of the Iranian nation state.

Nevertheless, the picture is not entirely positive. Virtual space can be vulnerable, especially when coercive governments choose to limit that space. We should also remember that the changes described above have not been positive in any sense for Bahai’s or members of certain political groups such as Leftist groups or Mujahedin-e Khalgh, who remain the primary targets of suppression and persecution in Iran. The current political climate shows how vulnerable virtual space can be when restrained by oppressive regimes.

Since the hardline Principlists came to power, activists have been targeted on a variety of fronts. Many newspapers have been shut down and several individuals have been arrested or forbidden from leaving the country. New media, such as the Internet and weblogs, have not escaped. The fledgling civil society in Iran is under great pressure. The current government seems particularly threatened by transnational activities, as demonstrated by the arrests of a number of Iranian–American academics and the harassment of some Iranians who have contacts with people living outside Iran. These developments have led the American government and the UN to enforce harsh policies towards Iran, which in turn have further reduced the possibilities for Iranians to leave Iran and for those living in diaspora to provide financial support.

Nation States attempt to control transnational (virtual) networks

Transnational networks can be a factor in redefining local power relations. After years of physical and virtual separation, the impact of transnational connections over the past decades brought new possibilities and challenges for the ways in which Iranians could negotiate and reshape the locality of their actions. These transnational interactions have proven to be influential in changing patterns of thought among those within the Iranian diaspora who are politically inclined. Indeed, 25 July 2009 provided a historical moment in the way that the Iranian diaspora united in support of the social movement in Iran. In this support we see a shift in political activism from partisan political activities towards (social and political) support for the movement in Iran. New media such as SMS, Facebook, Youtube, (photo)blogs such as Tehranlive.org, and the social network site Twitter have been adopted to mobilize and amplify the voices of opposition during and after the presidential election of 2009. aThe virtual space has been remarkably enabling, both in connecting the voice of protest in Iran to the global world, and in uniting the Iranian diaspora transnationally in support of the movement. Although Twitter, especially, proved to be quite resilient to censorship due to its access flexibility, the growing tendency of the Iranian government to block access to these new media and to suppress transnational activities and networks shows that these rhizomatic networks are not free floating. Although they might appear to be deterritorialized, separated from the nation state, they are in fact subject to persistent reterritorialization. Despite evidence that nation states are less important in a globalized world, they remain influential in defining terms and actions within transnational space.

Transnational networks change both the diaspora and those within Iran’s physical borders

The connections made possible by the Internet and new media, have and are transforming the way that those in diaspora view themselves along with the way the view their possibility to participate in a notion of Iran that transcends physical borders.

In that sense, this embedded virtual network has served as an alternative space, enabling a shift from the notion of a people exile to a people in diaspora for many. It has revealed and promoted rhizomic networks that transcend geographical limitations. This in turn has led to new types of actions: charitable, humanitarian, and political.

This piece is adapted from a larger article, The ‘Iranian Diaspora’ and the New Media: From Political Action to Humanitarian Help, originally published in the journal Development and Change, 40(4): 667-691.