Fighting for Women’s Rights: An Interview with Mahnaz Afkhami

November 16, 2011

The Accidental Leader Questions for Amsterdam50

November 19, 2011Rania’s position as woman, a Christian, and a human rights defender gives her a different perspective on many of the challenges in the region. She is very much aware of the issues which make minorities and women apprehensive. “There is a lot of fear in our region,” she stated. “We have deep-rooted fears that remain unaddressed. In Lebanon we have an anti-secular movement, which makes religious and political minorities apprehensive. The anti secular movement cannot achieve its goals unless it takes into consideration the fears of political and religious groups. Many Egyptians still believe Islam should be the state religion. So the Coptic Christians are afraid. There is a fear of Israel: fear that people will be moved around and Israel will shut down its borders. Women are afraid. Me as a Lebanese, I cannot pass on the right of nationality to my kids because they are afraid of sectarian inequalities. There is also the fear of the Islamists and Salafists. The military is not a fear. It’s a fact. They have ultimate power and are beyond the rule of law… Conformity is a big problem in the Middle East,” she stated. “I am afraid of my private rights and my civil rights.”

Rania asks, “Are we capable of managing the diversity we have?”

The following is an excerpt of that interview.

HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE MIDDLE EAST

RF: Human rights in the Middle East, this is a lot of work.

AS: Working to defend human rights anywhere is a lot of work, but in the middle east, there is also a lot of pressure. Do people understand what you are doing?

RF: There is mistrust in the international human rights instruments. So you hear, “It’s nice, but we don’t have it.” We don’t enjoy it. We don’t practice it. Many people ask, “Human rights? Where are human rights?” It’s as if you are talking about something inexistent. This is true to a certain extent. People do not feel or practice human rights in their day-to-day lives. They do not recognize when they are exercising human rights. I tell them, “Well you vote.” And they say, “Oh I didn’t think of it that way.” We tell them that human rights appear in many forms: when you form groups, freedom to comment on articles in newspapers, freedom to call in to a talk show and express your opinion, also represent the freedom of expression.

AS: I got the sense after living in Iran that many people thought of human rights for themselves, but not for others, or they thought of them as something used against them by the West, or as a luxury. Is this also true in your region?

RF: Yes it is a luxury because the basic rights are not there. We can’t blame people for that. It’s the reality they are living in. As for human rights is for them, yes. You hear, “I have human rights, but in practice I don’t. I have the right to express my opinion, but I am not tolerant of disagreement.” I don’t know if this human rights or tolerance. I know they are two faces of the same coin. It may be more tolerance than human rights. Human rights are human rights for all and not only for me.

If you take the issue of torture, you will find a wide spectrum — even among the elite and the educated and the middle class — who will say if he is a collaborator with Israel, he needs to be punished severely so that he will not do that again. If you talk about the death penalty, you will hear if a criminal went into a house and killed a family, for example, he should be hanged right away. so where is fair trial? right to life? Even among these circles that are considered to be more exposed, who read international papers, we find they don’t have a deep comprehension of human rights and what it is really. If someone does something wrong, people forget about human rights. They are ready to dismiss with justice and condone torture.

Salafis and jihadists are also vulnerable. People think it’s okay to torture them and raid their houses. They think it’s okay to tap their phone calls, follow them, observe them, you can do all the intelligence work with them and it is ok as long as it makes us feel secure. Everyone thinks these people are dangerous. No one thinks that we are violating their privacy rights or their personal security and rights.

AS: What you are saying is that in the minds of many, security trumps rights.

RF: Yes. This is true. Especially after 9/11, and not only in the Middle East, but around the world.

This is true all over the world.

—

WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE

RF: In Jordan, you find women more and more wearing the veil. You see the burqa and the niqab. In Amman you see this more and more. Ten years ago you rarely saw a burqa or niqab in Amman or in Cairo. Of course, some of the women wearing them here are making a political statement. And some people here respond by calling them Bin Laden’s wives. They say, “There goes one of Bin Laden’s wives.” People are negative here about the veil. I don’t want to call people here Islamaphobic, since most are Muslims. Maybe it’s extremist-phobic.

Even so, in Egypt, in Jordan, in Khartoum, especially in certain neighborhoods, will harass you if you are not wearing hejab. Even women will approach you and preach you.

Definitely things are changing in the middle east and elsewhere.

AS: What role are women playing in the Middle East, and how they can secure a stronger role?

RF: For me, if you are there and you are active, you gain a role. Frankly, there are few women participating.

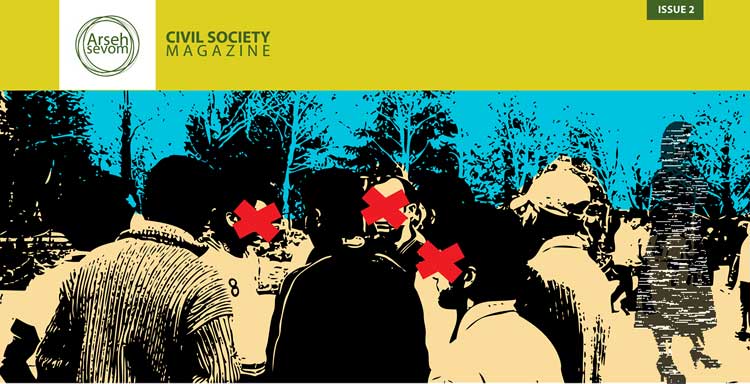

AS: So the pictures show us many, but you tell me there are few.

RF: There are few actually. Women can’t only go onto the streets, but they have to be part of the decision-making process. You don’t see women in positions of power or accessing those positions.

AS: Despite the participation of women, for instance, in the 1978 revolution in Iran, they found themselves marginalized. Basically, they heard, “Thanks for your help. Now go back to your homes and be good wives and good mothers.”

RF: Many people here are not gender sensitive. Both women and men do not consider the position of women. For instance, I was talking to a group of Iraqi human rights lawyers a few years ago. A man claimed, “Women here are in heaven. During Saddam’s regime, women working in the ministries got one-year maternity leave. Can you imagine? We had to work to support them. Thank God the new government changed that law.”

One of the women participants said, “But this is forcing women out of public service.”

The lawyer responded, “They shouldn’t work anyway.” He went on to explain that women had enough work at home, he called this their “natural duty.” He added, “Why did God make it possible only for women to have children?”

I lost my cool listener attitude and responded, “Well in God’s wisdom, he made women stronger and smarter.” I was the sexist then.

ON CHANGE AND THE MILITARY

RF: In Arabic, we have a saying: “Running away is three-quarters of manhood.” If you know you’re doomed, you don’t have to be a martyr. So, run away. Don’t be so courageous that you become a martyr. Bin Ali in Tunisia knew the right moment to run away. He knew the military had had enough of him. He made a deal with the Saudis, and poof, he was gone.

You have Mr. Mubarak who did not apply this funny saying, and he knew he was doomed. The military were very much aware that the people in Egypt did not want Gamal Mubarak [Hosni Mubarak’s son]. They sensed the people’s refusal of Gamal. They did not like the idea that Hosni Mubarak had kind of made him an heir to his throne. Egypt does not have a monarchy. The people would not accept this, and the military knew this. They didn’t want Gamal Mubarak either. They wanted elections and someone from the system, like they had when Sadat was assassinated.

Mubarak knew the military was not with him, but he was ready to be a martyr. The military had told him, please leave, we are not going to protect you anymore.

When you look at Libya, Syria, Bahrain, and Yemen, you see that the military, which is the biggest apparatus in the Middle East, did not tell the leaders that they had had enough. You see that the power to change governments is not always with the people, but with the military.

The power center is the military. So the power center is now negotiating on behalf of the people. This is what is happening in Egypt now. The military is negotiating with the Muslim Brotherhood, because they are the most organized of all the groups. We will see what will happen.

AS: What you are saying is that in order to make change in these heavily militarized regions you have to eventually negotiate with the military.

RF: Yes.

AS: How do you move beyond military control to civilian control?

RF: We need to learn from the Turks. They have been doing this for a long time now. In Turkey they have more checks and balances. We don’t have them at all.

AS: So in a sense you have to move step-by-step with the military in order to get them to buy into civilian rule.

RF: Exactly. But you also have to strengthen civil society. You have to strengthen education. You have to strengthen activism. You have to restrict military rule to military matters. In this region, the military also enjoys other privileges which makes them almost untouchable.

What has changed, maybe, in Turkey over the past five years is the awareness of rights. This was illustrated by the issue of veils in the universities. Women protested. They said, this is my right.

AS: When the military has so much power, it limits the involvement of women. It makes it difficult for women to negotiate with power.

RF: We have a very patriarchal society. Women can be doctors or engineers, but they cannot be activists. They have to submit to the society. Even women see activists as trouble-makers. Even educated women see those women who struggle for rights and choose to be activists as trouble makers.

AS: That’s why there are so few activists: you are always making trouble by pushing the society to do better. People, men and women, would prefer it if we all just were quiet.

RF: Exactly. Activists push the limits of society. They make it uncomfortable. It isn’t just men who discriminate against women. Women discriminate against women.

SUCCESS

AS: Can you point to an initiative that is going well?

RF: There are a number of initiatives going well and doing something good. For instance, in Lebanon there is a movement for women to be able to pass on their nationality to their children. Now, my child would not be Lebanese unless his Dad is Lebanese. Women are fighting for this right too, and it is going well.

The general uprisings in the Middle East are good because they are showing that suppression cannot go on forever. Even if the uprisings are violently oppressed, people know that suppression will not go unremarked forever. This is the start of checks and balances. Even the military has to think about what will bring people on to the streets. This may not be so obvious now, but it will become more important.

AS: For this to continue, average people, people who are not activists, have to become more engaged.

RF: Absolutely. This needs to continue at the grass roots level.

INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS

AS: It was easy to unite people to topple Bin Ali in Tunisia and Mubarak in Egypt, but it isn’t easy to unite people for all the discussion and quarreling and compromise that makes up a democracy. How do you keep people engaged? Do you have any ideas?

RF: Activists have to play a big role. Education has to play a big role. In the Middle East we are not educated that we are citizens. Education is about science and math. We learn that the authority of the Mom and Dad has to be respected. Older people must be listened to. This is not citizenship. We are not educated to state what we find wrong.

The pressure to be the same, to be part of the dominant culture is not good. We have to educate more about individual rights. We should educate from the individual up to the community. When individuals learn about their rights, they naturally respect those of other individuals.

Law enforcement also needs to be involved in protecting the rights of minorities. We need more education, more awareness.

AS: We need more tolerance.

RF: Individual space is lacking here, so there are very much blurred lines between what is individual and what is group. The notion of individual rights is a difficult one. It will be fought against by the collective.

AS: People seem to think democracies represent the will of the majority at all costs, when in reality they are responsible for protecting minority voices and opinions.

RF: It is important for democracies to protect the rights and opinions and even the presence of minorities. Minorities need to be protected to strive and flourish under the majority, and this is not easy.

AS: It isn’t easy anywhere. In the Netherlands, which has a strong dominant culture, many people have a hard time imagining what it’s like to be a minority. I saw this when living in Iran as well. It was hard for many to see differences among them. Many people had a hard time understanding that not everyone in their society was part of their culture.

RF: I wanted to make a statement about the law passed in France about the niqab. I believe this is a violation of human rights. Maybe the law should state that if there is a woman who is wearing a niqab and the secuirty officer needs a clear identification of who she is, then she must show her face. But if this is forbidden because it is against the majority or the norm in France, what is this? It is my right to wear whatever I want. Full stop. What about minority rights? If I have done something wrong, if there is a threat from me, ask me, Please remove your veil. If not, my rights as a minority should be respected.

I think this law is very racist and against human rights.

I would like to be tough, what is the difference between this law and the morality police in Saudi Arabia and Iran? It’s the same stupid mentality. If I want to wear a short skirt or a veil, it’s nobody’s business. How can France or Europeans condemn the morality police in Saudi Arabia or Iran, when they do not condemn what they are doing? Short skirts do not mean I am more free than someone in a niqab.

AS: I have also learned that from experience. I learned about my prejudices from meeting and working with women in hejab. I hate to admit that I had these negative ideas about women in hejab or other religious clothing, but I did.

RF: I was not born with my present point of view. I also have had my prejudices. The first time I went to Yemen in 2001, I felt sorry for the women. I felt they were under suppression. It was to my surprise that women in Yemen were human rights fighters, they believe in things, they think, they are liberal, they want to be part of their society, they have so many ideas. I went to Yemen thinking these women were ya haram, pity on them. But no, pity on me! I know nothing. I know shit about how I thought because they were wearing niqab they were not thinking. That’s wrong.… They are wearing niqab, but they are thinking. They are so open minded and so enriching to talk with. They are really nice women.