Contributors

November 9, 2011

“Are we capable of managing the diversity we have?”: Human Rights in the MENA Region

November 17, 2011By Hooman Askary

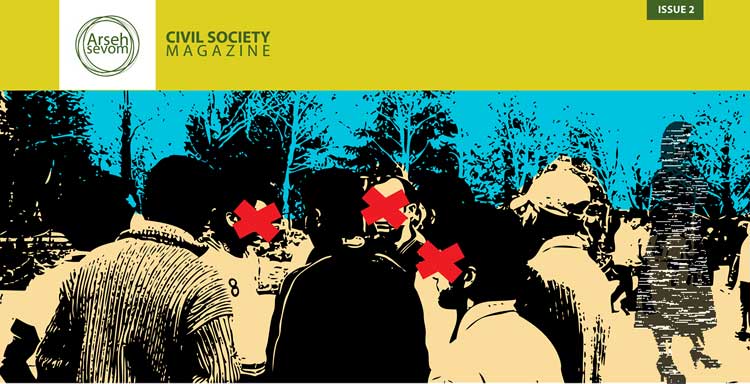

For more than three decades, the rare images of women coming out of Iran primarily showed them in the required Islamic hijab, implying absolute compliance and complacency. Disparate accounts seldom raised doubts about the way women saw their role in society. Information and communication technologies altered that image once and for all. The world was able to see different images of Iranian women through the lens of netizens. It appeared that the imagined complacency had never even existed in the first place. In 2009, Iranian women really made the world stop and notice. They were the pioneers of the national opposition and demonstrations against the Islamic Republic which became known as the Green Movement. That movement soon became personified by a young woman who lost her life to a bullet from the Basiji militia. Unlike most of the national heroes of Iranian patriarchal society, a young woman, Neda, became the face of the nation. She was special because she was not special at all. She was the Iranian girl next door; one worlds apart from the image endorsed by the Islamic Republic.

Almost two generations before Neda and her peers, Mahnaz Afkhami was born. There were not a lot opportunities available to a girl born in the Iran of 1941. Still Mahnaz Afkhami managed to surprise everyone and have an exceptional career, working hard for the advancement of women in Iran.

A brief glance at Mahnaz’s bio would tell you something like this: she started her life as an activist quite early, left Iran for the US at the age of 13. At 17 she joined a trade union. In 1967, she returned to Iran and worked as a university professor. While teaching at the National University of Iran, she founded the Association of University Women and then became secretary general of the Iranian Women’s Organization. In 1975, Mahnaz Afkhami joined the cabinet as Minister for Women’s Affairs. Her website relates this to her “year of intense activism during International Women’s Year (1975).” To mention a few of those years’ achievements, Afkhami and her colleagues, managed to change Iranian laws so that by 1978 women had gained equal rights to divorce and the minimum age of marriage for girls was raised from 15 to 18. Afkhami also initiated and sponsored a package of laws and regulations to support women’s employment.

This was all reversed by the success of Ayatollah Khomeini and the Islamization of the revolution. Khomeini represented tradition against the Shah as the symbol of modernity. In an interview with the author, Mahnaz Afkhami recalled how women’s issues were the main source of contention. “Ayatollah Khomeini came to power in February [1979] – before there was any constitution or government or any other radical changes – first of all he annulled the family protection law.” Of course, the changes brought about by the Islamic Revolution in Iran not only affected Afkahmi’s life’s work, but also her own life. While on a mission in the USA, a death verdict in abstentia was issued against her on the charge of “Corruption on Earth and warring with God.” That was the infamous charge brought against many high ranking royal officials including Amir Abbas Hoveyda, the former Prime Minister. Thus began Mahnaz’s life in exile.

Even in exile she didn’t cease working towards her goals both in her homeland and around the world. The clerics in Tehran were becoming more reactionary, beginning with the introduction of compulsory hijab for women, banning women from participating in certain roles in society, closing down universities for more than 2 years while revising all pedagogical materials to endorse a specific ideology favoring their theocracy,and banning music and dancing. During those dark days, Mahnaz carved out a new role for herself as an activist determined to advance women’s rights – this time in the scope of the world. She continued assisting her compatriots in Iran to preserve their achievements while resisting the devastating effects of the revolution. Soon after the revolution, she established the Foundation for Iranian Studies in 1981. She became associated with many human rights organizations; served as vice-president of “Sisterhood Is Global” Institute for 10 years; joined the advisory board of “Women’s Division of Human Rights Watch” and in 2000 founded a new organization– Women’s Learning Partnership for Rights, Development, and Peace (WLP). Mahnaz has penned multiple books, articles, and booklets which have been translated into several languages and used in universities, women’s NGOs, and international organizations as references.

It is now almost 40 years that Mahnaz Afkhami has been fighting for women’s rights and against all sorts of gender apartheid, as she writes, “in the name of tradition, religion, social cohesion, morality, or some complex of transcendent values.” The question remains whether or not her campaigns inside Iran have had any effect on the lives of women? Did all of the achievements vanish overnight in 1979 when the mullahs took over?

Afkhami believes that the movement never stopped and says, “The green movement in Iran is the continuation of what had been started nearly a century before and gone through ups and downs, changes and evolutionary and revolutionary transformations.” She describes the current situation in Iran as “another stage in an ongoing movement.”

Sima, a retired Iranian woman in her late 50s, also believes that the achievements Iranian women have made in recent years, under immense pressure and persecution, are the continuation of an enduring movement which started before the revolution and never stopped. She considers the enlightenment process and women’s resistanceso effective that, if not there, “Iran would be another Afghanistan with an even worse situation for women.”

Another Iranian woman in her late 50s, Maryam, recalls how she received proper education to become a teacher and live independently from her family. She also mentioned that her peers would adopt new cultural norms and shed the hijab “as soon as they got on the buses transferring them from their small hometowns to their colleges in the bigger cities.” But as life-changing an experience this process was for women, it also may have contributed to a backlash. Looking back at those days, Afkhami writes on her official website,

“It seems to me that our main mistake was not that we did not do other things which we should have done. Our main mistake was that we created conditions in which the contradictions related to modernity, progress, equality, and human rights, especially women’s rights, increased and the reaction to our work put perhaps too much pressure on the country’s social fabric.”

Mahnaz Afkhami says she thinks what happened then was “a new experience globally to have an expression of political religion as an ideology.” She further explains, “It was not only women who were misled by the new slogans and new ways of mobilizing, but also a large number of intellectuals of various groups, [even] policy makers and politicians thinking at the time that this was going to be a democratic and participatory movement; that it was going towards a more human rights oriented and open society, which of course, turned out to be not quite so and even the exact opposite. The difference between women and other groups was that they were the first to recognize their mistake and they were the first to stand up to the new rulers and show their displeasure with them.”

Afkhami points to the use of terms with different meanings by Ayatollah Khomeini such as his stance against the idea of “women as sexual objects” – which is also a stance taken by feminists. What he meant, however, was not that women should be seen acting as people with equal rights, but “people wrapped up in black veils and kept away from mischief.” The same was true for “democracy, freedom, and legitimacy.” What those terms meant to many was not what they meant to Khomeini. The use of cherished terminologies used with different meanings contributed to misleading many.

Today Iran has a mostly educated, but deprived majority raised by the women whose identities were already formed and developed in the pre-revolutionary era. This might be one of the reasons that the ongoing clash of discourses evident in the recent movements in Iran emerged in the first place. Afkhami sees the conflict due to Iran’s “well-developed, sophisticated and modern civil society especially in terms of women’s activism, women’s organization, and women’s mobilization and awareness.” She adds that when such a modern civil society faces a set of anachronistic laws and system of government there is a constant conflict; just as the evident clash between the ideology of the Islamic Republic and the reality of women’s lives. At every step the government has had to be pushed back and to some extent they have been pushed back. Although Afkhami also acknowledges that any further visible steps such as ending compulsory hijab would, in their eyes, question the legitimacy and authenticity of the Islamic regime. The amount of time and energy and resources that have been spent by the Islamic Republic to simply keep head scarves on women’s heads is astounding. They continue to do so because symbolically it is their claim to authenticity. Does that mean that women are pushed back for yet another phase faced with the iron-fisted policies of the clerical regime? Afkhami states, “So far as women are concerned they are doing whatsoever humanly possible against these limitations and harshness and aggression.”

Afkhami and her colleagues are also doing their part. She says they are trying to keep the women inside the country connected to the activists in other parts of the world, especially in Middle East and North Africa. They have translated many textbooks, manuals, and learning tools and put them on the web. They have also translated their accounts of what is going on in Iran and circulated them among the tens of thousands of NGOs worldwide. As for the new wave of exiles, they have been trying to support them and help them maintain their connections with their constituency inside and to survive outside of Iran.

An old English saying suggests that a daughter ought to be judged by the mother. The pictures and video clips of Iranian girls on the internet seem nothing like those of Mrs. Ahmadinejad’s with her black veil showing only one third of her face. Perhaps this is the context wherein Neda was born and soon became the face of a nation long misunderstood, misinformed and, “mis-led”.