#Iran — Time for Attention to Human Rights

November 29, 2013

#Iran: I’m Dreaming of Citizens’ Rights

December 26, 2013Arseh Sevom— This week’s review looks at issues of free expression. How would Iran’s culture change with open communication and the free flow of information? When will Iran finally have a safe public forum for voicing dissent? Despite the hopes for increased space for expression, in recent weeks, rappers, activists, technical staff, and others continued to be arrested. The nuclear agreement may represent a step away from international isolation, but Iran’s people still have a long way to go before breaking down the barriers to dissent and free speech.

By Peyman Majidzadeh

Freedom of Expression: Dream or Reality?

Freedom of expression has always been a major issue in Iran’s post-revolution history. The Islamic government began restricting expression from the very early days of the revolution. Compulsory Hijab [en] for women was arguably one of the earliest examples of these restrictions. Many women were not happy with the decision at the time, but their protests did not lead to a result; their voice was censored along with their beauty. Women were not the only repressed group. Some political parties and ethnic and religious minorities were among the early victims as well. In order to be heard, every voice had to go through the regime’s channels.

The situation of freedom of expression was never satisfactory. However, the controversial 2009 elections marked a new round of crackdowns. Many were out on the streets, demanding their basic rights, and the government responded with arrests and repression. No dissenting voice was allowed. It was a matter of “national security” – a leading to the imprisonment and sometimes death or execution of many. As a result of the violent repression, people left the streets. In the streets, they felt too vulnerable.

However, civil society, like water, finds its way. The rise of the internet and social networking provided dissenting voices with a suitable channel for the expression of rights and demands. Social networks played a vital role in the Middle East’s movements over recent years and the people of Iranian made use of them as well. The government felt threatened by the digital sphere and expanded its efforts to take more control over it. Significant budget was allocated and spent and new laws were passed. Recently, the international free-speech organization, Article 19, published a detailed report on Iran’s Computer Crimes Law [en] and its effects on civil society.

No Freedom of Expression on the Streets; No Freedom of Expression Online

Rouhani was expected to open some space for dissenting voices. He did well in foreign policy, but arrests continue at a pace. Last week, a popular musician and a prominent IT website’s (Naranji) technical staff [en] were arrested. Staff of Naranji have been accused of acting against national security and cooperation with foreign networks. Their website is unblocked, but the location and situation of those arrested is still unknown. The internet was the last sanctuary for Iranian people, and now Iran’s cyber army is taking full control over digital space. There is now no freedom of expression on the streets, and no freedom of expression on personal computers. In an interesting infographic, Article 19 shared the Iranian recipe for online repression.

What Would True Freedom of Expression Look Like?

I have been thinking about the issue of “freedom of expression” over the past few days. Many Iranians insulted Fernanda Lima and Lionel Messi [en] on social networks such as Facebook, and many others apologized for that the insults made by their cohorts. Now everyone is speaking about the cultural roots of the action. But would such things happen if Iranians were “truly” free to express themselves over the Internet, and even more importantly, had free access to the flow of information throughout their lives? Can we separate the cultural roots from the ongoing repression in the country? These roots are the result of many factors, including the digital crackdown. Iranian people face threats of arrest or even wors, if they express dissent about topics including politics, religion, minorities’ issues, and women’s rights . Give them “true” freedom of expression and Lima and Messi would be the least of their concerns.

Saeed Mortazavi’s Letter to Parliament

Saeed Mortazavi, the former head of Iran’s Social Security Organization, has been out of the media spotlight for a while, but he is not a man to remain silent for long. On Monday, December 9th, he wrote a letter [fa] to the parliament’s Article 90 Commission and provided a list of MPs who had received gift cards from his organization. The controversial letter triggered objections from a number of members of parliament, including Tehran’s MP Alireza Mahjoub who claimed that the letter is a lie and publishing it could result in “legal prosecution.” The letter seems to be the beginning of a new round of tensions between Mortazavi and the parliament.

Student Day: A Good Opportunity to Demand More

Saturday, December 7th marked Iran’s National Student Day. The day was named after the killing of three students by Iranian security forces during a peaceful demonstration in Tehran on December 7, 1953. Now the day is an annual meeting for reformist students who try to realize their rights. On Saturday’s meeting in Shahid Beheshti University, reformist students demanded the Rouhani free political prisoners [en]. Although Basiji students expressed objections on Iran’s nuclear deal, it seems that the Student Day provided a good opportunity for Rouhani to forge a closer relationship with students who form a significant proportion of Iran’s population. Now the reformist students demand action!

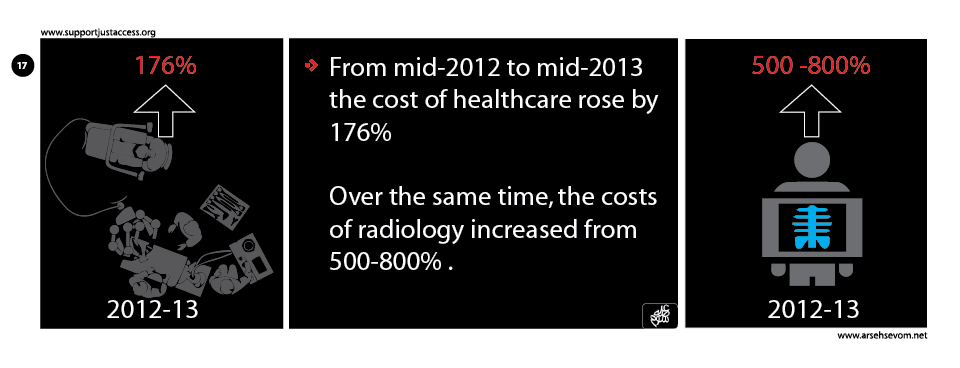

Medical Expenses Force Iranians into Poverty

For more information about the state of Iran’s economy, see Just Access

Medical expenses grew drastically after imposition of international sanction on Iran. Together with Iran’s poor economic situation, they have forced many Iranians into poverty. According to the head of Iran’s Medical Council, Alireza Zali, 7.5% of Iranians are annually dropping below the poverty line [en]. The rate is almost double in Iran’s expensive capital, Tehran. According to Zali, the rate was 3% in the year 2007. The Iranian government needs to deal with the issue as fast as possible, before it is too late for the patients who have suffered enough.

#IAmPayam: Iranian Gay Poet Reaches Out the World

Nogaam [en] is an online publisher that freely distributes the work of censored Iranian authors. The foundation collects support for Iranian censored works and publishes them in online space. In its recent project, Nogaam is trying to publish an Iranian homosexual poet’s book, “White Field.” The poet, Payam Feili, published his first book “The Sun’s Platform” in Iran when he was 19. The book was heavily censored by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Now he says:

“I don’t allow anybody, not me, not others, not even the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to censor my books”

Join the I Am Payam [en] campaign to help Payam express himself to the world.