Newsletter

October 31, 201427 Kurdish Political Prisoners on Hunger Strike

December 21, 2014

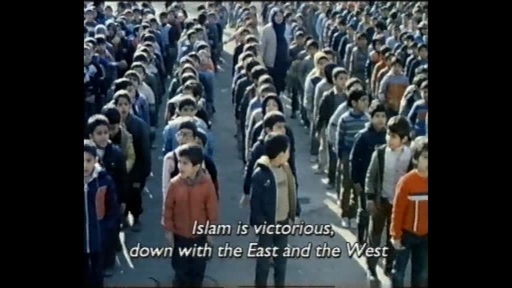

Screenshot from the 1989 documentary Homework by Abbas Kiarostami

First Day of School

The first of the Iranian month of Mehr, which in 2014 fell on September 23, is the first day of school in Iran. For children and their families all over the world, the first day of school is a big step. Everywhere, children learn that the world of their home and of their family is very different from that of school. They can be confused by all the new rules and norms they encounter. For many families in Iran, that normal process is exaggerated. Preparing children for school in Iran involves more than buying pencils and notebooks. Many parents are faced with the challenge of explaining complex rules of behavior to children emotionally incapable of understanding them.

During the first years of the revolution special teachers who were part of the Revolutionary Guards could come to the schools at any time to pry information from the children. This is a special kind of horror for parents and children alike. “It was quite normal for the regime,” Kevan says. “They were ready to kill their own children for the sake of the revolution. They had no shame in trying to get other’s children to inform on their own families. It may be salt on the wound to say this. But it is a wound.”

You Have to Conform

Kambiz1 (31) stated, “From the first day you have to conform.” He went on to discuss his first day of school:

“I was so excited to go to school. I want to go to school. I want to go to school. I demanded. The first day I woke up early. After that first day, I wasn’t so excited to wake up and go to school. Before I went, my mother told me, ‘You have to tell people that your father is on a business trip.’ I thought, why should I tell them that when I know he is in prison?”

It was three weeks before anyone asked Kambiz about his father. He responded that his father was away on business and did not return until very late. “It made me feel so bad,” he said. “It is such a paradox for a child to know you are lying. I couldn’t understand why I had to do it.”

The first years of school for Kambiz corresponded with the end of the Iran-Iraq war and the death of Khomeini. “It was unusual to have a relative who was a political prisoner then,” he said. This was especially true in his neighborhood where many of his schoolmates had relatives who had gained power after the revolution. “I could not talk about it with anyone.”

Politicized Religion

Maryam lived in the United States until she was nine, where she went to a predominantly African-American Sunni mosque and attended weekly Shia discussion circles. She describes her family as “religious intellectuals,” explaining that as a result they had fewer taboos than many other families.

“… I learned to draw a line between the religion we had and the state religion/religious propaganda. Frankly that’s the only way that any religion can be saved in Iran if you are not brainwashed. I learned to be suspicious of whatever religious and historic education we got at school.”

She was suspicious of the “ultra-Shia stuff” they were taught in school but rarely discussed this with her teachers.

“Later, in college, I would sometimes argue with religious teachers and even the lady at the door telling us we were not dressed appropriately from a ‘fellow Muslim’ perspective. I tried to convince them that their lifestyle is not the only Muslim lifestyle out there. However I wouldn’t mention my unconventional-for-a-Shia beliefs. About politics, there was always a line not to cross publicly. I think I was very aware of it from 11 or 12 years, if not earlier.”

Don’t Talk About the VCR

The first time Payam (31) understood that he could not talk about things that happened inside the house, outside the house was the day before his first day of school.

“Before my first day of school, my father told me not to talk about our VCR. We exchanged videos in the neighborhood and had family movie nights with neighbors. Of course, this was forbidden when I was a child. My father told me that teachers might draw pictures of the VCR and ask if anyone in the class knows what it is. He warned me not to volunteer that I knew. ‘I don’t want you to lie,’ he told me. ‘Just remain silent. If they know, they will come to take away the VCR,’ my father told me. ‘And they might take me away as well.’ I had a hard time understanding why there were things we couldn’t talk about outside the house, but I didn’t want my father to be taken away.”

A year later, special teachers assigned by the Revolutionary Guards did come to the school to try to get information from the students, now six and seven years old. Payam was silent, but other children in the class did volunteer information. “I was very quiet in school. Even though I participated in discussions, I did not easily make friends, and I did not talk very much outside of structured discussions.”

For many of the people I spoke with for this article, especially those in their thirties, the need to hide information was tied to a sense of fear. Mostafa explains, “For me it was about danger, not lying.”

The Way We Live

On Aida’s first day of pre-school in Tehran just two years ago, she lifted a glass of water to toast the health of her new friends. “Salam-a-ti,” she said happily. “To your health.” Alcohol is illegal in Iran and some could connect her toast to her family’s private actions. That afternoon, Aida’s mother was forced to explain that there were things that could be said at home that absolutely could not be repeated in public. At just three-and-a-half years of age, Aida could not understand why she had to keep some things quiet, just that she needed to. Her father laughed when he recounted the story and then added, “She was upset, but that is the way we live in Iran.”

Things have changed a great deal in thirty years. Rooftops all over Iran are covered with illegal satellite dishes. The regime continues its fruitless battle to isolate the population from the outside world, currently doing battle with messaging apps and arresting people for spreading jokes or making videos.

Even with all the changes, Payam cannot imagine raising a child in Iran today. “I don’t know how I could protect my child or explain why some things are okay to talk about and why some things are not. It’s hard for me to imagine.”

They say that a mark of intelligence is the ability to hold contradictory ideas without having your head explode. For many of Iran’s youth, this is the only way to stay sane and safe every single day.

1 All names have been changed to protect identities

By Tori Egherman (@ETori).

This content is available in: Farsi. Originally published on Article 19’s Azad Tribune Read her previous piece for Azad Tribune: The Speech Squeeze.