Human Rights Organizations–Cooperating for Change

February 14, 2015

Renew Mandate for Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Iran

March 12, 2015Arseh Sevom — A group of 36 organizations including Arseh Sevom sent a letter to members of the United Nations Human Rights Council asking for a renewal of the mandate for a Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Iran. As part of the letter, this fact sheet was included. It updates the current human rights situation in Iran. The current Special Rapporteur, Dr. Ahmed Shaheed, recently stated about the capacity for respect for human rights, “Iran is the the country in the world with the biggest gap between practice and potential.”

FACT SHEET: 2015 update on the human rights situation in Iran

Iran faces a chronic situation in which serious violations of human rights continue to be perpetrated by the authorities, particularly Iran’s security, intelligence and judiciary authorities. Below are some key indicators.

1. Death penalty

Iran has had the highest per capita execution rate in the world for several years in a row. It retains the death penalty for a wide range of offences, including broad and ill- defined crimes such as “sowing corruption on earth,” as well as some offences that do not constitute “most serious crimes” under international law. The number of executions in the country has reportedly increased in recent years, from at least 580 executions in 2012, to 687 executions in 2013, to 753 executions in 2014. Some executions are carried out in public.

Iran has had the highest per capita execution rate in the world for several years in a row. It retains the death penalty for a wide range of offences, including broad and ill- defined crimes such as “sowing corruption on earth,” as well as some offences that do not constitute “most serious crimes” under international law. The number of executions in the country has reportedly increased in recent years, from at least 580 executions in 2012, to 687 executions in 2013, to 753 executions in 2014. Some executions are carried out in public.

In many cases, courts imposed death sentences after proceedings that failed to respect international fair trial standards, including by accepting as evidence “confessions” elicited under torture or other ill-treatment. Detainees on death row were frequently denied access to legal counsel during pre-trial investigations.

Scores of juvenile offenders, including some sentenced in previous years for crimes committed under the age of 18, remain on death row; others were executed. The revised Islamic Penal Code allows the execution of juvenile offenders for qesas (retribution) and hodoud (offences carrying fixed penalties prescribed by Islamic law), unless a judge determines that the offender did not understand the nature of the crime or its consequences, or the offender’s mental capacity is in doubt. Saman Naseem, who was arrested when aged 17, was sentenced to death on charges of Moharebeh (“waging war against God”) and Ifsad Fil Arz (“corruption on earth”) for his alleged involvement in armed activities. Security authorities allegedly tortured him in detention to force a “confession.” Rights group Iran Human Rights identified at least 14 executions in 2014 of persons who may have been under the age of 18 at the time of the crimes for which they were convicted.

The revised Islamic Penal Code also retains the penalty of stoning to death for the offense of adultery. At least one stoning sentence was reported to have been issued in Ghaemshahr, Mazandaran province in July 2014. No execution by stoning has been reported since 2009.

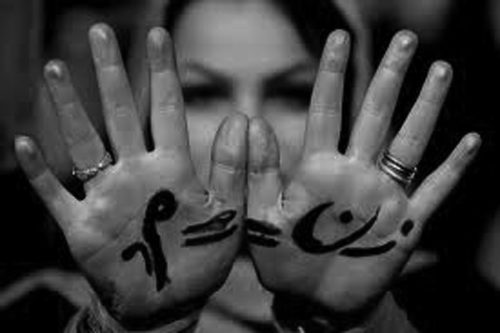

2. Women’s rights

Despite minor improvements under President Rouhani’s administration, such as the lifting of many gender-based quotas in universities, women in Iran remain subject to widespread and systematic discrimination in law and practice. Official policies aimed at restricting female employment and encouraging women to stay at home and pursue “traditional” roles as wives and mothers continued. While women occupy about half of all university student places, their economic participation in Iran is only 12.8%, five times lower than men, according to government figures. Personal status laws that accord women subordinate status to men in matters such as marriage, divorce, child custody and inheritance remain in force.

Despite minor improvements under President Rouhani’s administration, such as the lifting of many gender-based quotas in universities, women in Iran remain subject to widespread and systematic discrimination in law and practice. Official policies aimed at restricting female employment and encouraging women to stay at home and pursue “traditional” roles as wives and mothers continued. While women occupy about half of all university student places, their economic participation in Iran is only 12.8%, five times lower than men, according to government figures. Personal status laws that accord women subordinate status to men in matters such as marriage, divorce, child custody and inheritance remain in force.

Two population-related draft bills that remain under parliamentary consideration threaten to reduce women’s access to sexual and reproductive health services. One draft bill proposes to prevent surgical procedures that permanently prevent pregnancies and imposes criminal punishments on health professionals who preform such procedures. The other bill seeks to reduce divorces and remove family disputes from the courts in favor of mediation.

A peaceful gathering in front of the Iranian Parliament in Tehran on October 22, 2014, during which demonstrators demanded a government response to a spate of acid attacks against girls and women across Iran, ended with the beating and arrest of some of the protesters by security agents. Authorities forcibly dispersed another gathering outside the Iranian Judiciary building in Isfahan, with plainclothes agents using batons and tear gas against the demonstrators. Authorities held women’s rights activist Mahdieh Golroo, one of the participants arrested after attending the peaceful protest outside the parliament building, for three months, only releasing her on bail on January 27, 2015.

3. Rights of minorities

Religious and ethnic minorities continue to face violations of their rights, both in law and policy. Members of the Bahá’í faith are systematically deprived of the rights to university education, state employment and business licenses, and to hold religious gatherings. In January 2015, at least 100 Bahá’í were imprisoned for their religious and community activity. Christian converts, including those involved in informal house churches, face arrest and imprisonment. At least five members of the Sufi Muslim Gonabadi Dervish community remain behind bars, for the peaceful exercise of their basic rights.

Despite constitutional guarantees of equality, members of ethnic minorities, including Ahwazi Arabs, Azeri Turks, Baluch, Kurds, and Turkmen, continue to face a range of discriminatory laws and practices, affecting their access to basic services such as housing, clean water and sanitation, employment and education. Despite some minor opening, the Iranian authorities continue to deny ethnic minority communities the right to learn their mother language, particularly at the early stage in education. Members of minority groups, particularly those who seek greater recognition of their cultural and linguistic rights, face persecution, including arrest and imprisonment. Five members of Yeni GAMOH, an Iran-based Azerbaijani-Turkish organization, are serving nine years in prison reportedly for charges steaming from their cultural and political advocacy.

4. Freedom of expression and the media

Attacks on the freedom of expression have increased in the past year, which has seen a sharp rise in arrests for internet-related offenses, as well as continuing arrests of journalists and bloggers and the enforced closure of newspapers. With at least 30 journalists in prison at the start of 2015, Iran is the second leading state in detaining journalists globally according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. The Tehran correspondent for the Washington Post, Iranian-American journalist Jason Rezaian, had—as of this briefing—been detained for over six months without access to a lawyer or publicly disclosed charges. In November 2014 Iranian officials said that Jason Rezaian would “soon” be released.

Since October 2013, at least seven domestic publications—Bahar, Aseman, Ghanoon, Roozan, Ebtekar, 9 of Dey and Ya Al Sarat Al Hossein—have been temporarily or permanently shut down by authorities.

In April 2014, Iran’s Revolutionary Court sentenced eight young Iranians active on Facebook to a total of 127 years in prison, which an appeals court later reduced to 114 years. The courts found them guilty of “acting against national security,” “spreading propaganda against the state” and “insulting Islam and state officials.” In November 2014, Iran’s Supreme Court upheld a death sentence for Soheil Arabi “insulting the Prophet” in posts on Facebook. The Supreme Court’s ruling also, arbitrarily and unlawfully, added a new charge to Soheil Arabi’s conviction of “corruption on earth.”

5. Prisoners of conscience and political prisoners

Iran continues to hold hundreds of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience unlawfully detained for exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association, assembly or religion, according to the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran. These prisoners include journalists, lawyers, human rights defenders, artists, bloggers, aid workers, members of the political opposition, student activists, and ethnic and religious minority activists. Many others are being held after being prosecuted and convicted by Revolutionary Courts in unfair trials that failed to meet international fair trial standards, raising serious questions regarding whether they were also targeted for exercising their basic rights. Many detainees have reported facing torture and ill treatment, including severe beatings, mock executions, and prolonged solitary confinement.

Human rights defenders currently detained in Iranian prisons include lawyer Abdolfattah Soltani, and journalist Mohammad Saddigh Kaboudvand, who is also a member of Iran’s Kurdish minority, whose detentions have been found to be arbitrary by the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. Iranian Green Movement figures and former presidential election candidates, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, and Zahra Rahnavard, Mir Hossein Mousavi’s wife and a prominent academic and political figure, have been under extrajudicial house arrest with no charges or legal proceedings since February 2011.