24 Human Rights Groups Call for a UN Special Session to Address Repression in Iran

December 19, 2019

Guardian Council: Budget and Expenditures of the Monitoring Boards

February 24, 2020This post is the first part of a series of articles about the Guardian Council based on research by Arseh Sevom. What it shows is an expansion of power by the Guardian Council and Iran’s Supreme Leader. The Guardian Council is not merely an institution with twelve members, it has offices all over the nation. Since 2001, it has been expanding its influence on elections through surveillance and demands for ideological conformity from candidates. In fact, in the 2020 elections, it prevented the candidacy of nearly every single reform-minded or independent potential candidate. This includes rejecting the candidacy of 90 sitting members of parliament, many of whom are affiliated with the reformists or independent.

See more in Persian or download the complete report in English

About the Guardian Council

There is a kind of recycle and reuse policy when it comes to members of unelected bodies. They serve on multiple committees and multiple councils. Their influence extends well beyond any one presidential administration.

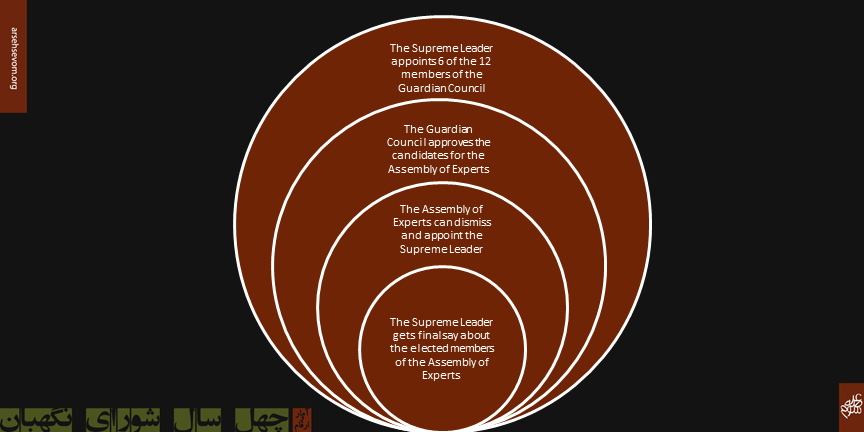

The Guardian Council has 12 members serving six-year terms. Six of the twelve are appointed by the Supreme Leader. The other six are selected by members of parliament from a pool of candidates determined by the head of the judiciary. Since the head of the judiciary is appointed by the Supreme Leader, this further enhances his control over the political process in Iran.

Over the past 40 years, the Guardian Council has been leveraged by the Supreme Leader to wield political power, keep opposition at bay, and to shape future leadership.

In addition, it is the Guardian Council that determines who can and cannot run for national office.

What our research into the Guardian Council demonstrates is the amalgamation of power in Iran. What began as a system of competing powers that could be checked, has become lopsided. Now the bulk of the power in Iran’s governing system is consolidated in the Office of the Supreme Leader. This happened under Ayatollah Khamenei’s rule. In the late 90s, the parliament voted to diminish its own power. In the 2000s, the shift of power increased.

Nowhere is this more obvious than with the Guardian Council. The notion that the Guardian Council is simply a board of 12 people – 6 clerics and 6 others – seems quaint. Today’s Guardian Council has offices in every province of Iran. It receives advice on legislative oversight from a shadowy group of “respected clerics” that is not known to the public.

The main purpose of the Guardian Council now seems to be controlling access to power. It has become a micromanager of elections through the development of election monitoring boards, which are neither independent nor impartial. These boards operate in every district. They don’t simply vet candidates to make sure that they meet the criteria set by the Islamic government, they surveil people who may one day become candidates.

- The offices and boards were established secretly without public knowledge

- The Election Monitoring Boards conduct illegal surveillance on people who may one day run as candidates, sometimes starting when people are still students

- The Election Monitoring Boards have final say in which candidates are allowed to mount election campaigns

Background

It wasn’t long after the monarchy was toppled that a new constitution for the Islamic Republic of Iran was drafted. Yet, even a revolution wasn’t enough to enshrine democratic rule. Instead of an elected president, the supreme leader (vali-faqih) succeeded the shah. The power of the presidency was limited by the authority of the supreme leader and the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament). In 1984, the Assembly of Experts was founded to monitor the operations of the supreme leader and to ensure succession.

After the formation of the new electoral bodies, the freshly minted constitution assigned oversight responsibilities of presidential and parliamentary elections to the Guardian Council.

In this article, we outline the ways in which the authority of the Guardian Council was expanded after the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, Iran’s first supreme leader. The focus is specifically on the establishment of election monitoring boards answerable to the Guardian Council.

Key Dates

1981: The first post-revolution parliament approves the Parliamentary Election Observation Code, creating the Central Election Monitoring Board to be established by the Guardian Council (Feb)

1982: The Presidential Election Monitoring Code is approved by parliament

1989: Ayatollah Khomeini dies and Ali Khamenei is placed in power

2000: The Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei calls for provincial offices of the Guardian Council:

“You [Guardian Council] have to consolidate your work. You need a reliable, strong, and agile organization that is well prepared to take on tasks year-round. You should hire election monitors in proportion to the number of voters in all the important voting districts. You must have access to an information bank.”[1]

2001: Election monitoring and observing is restructured and election monitoring boards answering to the Guardian Council[2] are established. The political deputy of the Ministry of the Interior states: “These offices are funded from the public budget and conduct illegal research and investigations about potential candidates.” [3]

2002: Provincial offices of the Guardian Council established

2019: In February 2019, Hassan Rouhani’s government sent the Comprehensive Bill of Elections to parliament to govern parliamentary, presidential, and council elections. If this bill is approved by the parliament, the composition of the monitoring boards will change dramatically once again. However, it is said that even if the bill is approved, it won’t be used in March 2020 elections.

Provincial Offices of the Guardian Council Established

“You have to consolidate your work. You need a reliable, strong, and agile organization that is well prepared to take on tasks year-round. You should hire election monitors in proportion to the number of voters in all the important voting districts. You must have access to an information bank.”

— Ayatollah Khamenei from a July 18, 2000 speech to the Guardian Council, quoted in Keyhan newspaper

- Provincial and district monitoring offices of the Guardian Council were set up with the expressed purpose of training of election observers

- This was done under the expressed orders of Supreme Leader Khamenei, who ensured a budget for the operations

- This was all initiated secretly and without media coverage[4]

Was the Restructuring of Election Monitoring Boards Illegal?

On 20 June 2001, Political Deputy of the Ministry of the Interior Morteza Mobalegh called the establishment of the District Monitoring Offices illegal.

“These offices are funded from the public budget and conduct illegal research and investigations about potential candidates.”

Presidential spokesperson Abdullah Ramazanzadeh also stated that the establishment of the monitoring offices was illegal and should be banned.

That didn’t stop The Guardian Council from establishing country-wide election monitoring offices.

In the August 17, 2003 edition of the Islamic Republic Newspaper, attorney and member of the Guardian Council Sayed Reza Zavare’ie stated:

“After negotiations with officials of the Office of Management and Planning, the Guardian Council received approval to create 384 positions for the Guardian Council in Tehran and provincial and district offices. The budget for the salaries of these employees throughout the country was published and approved in the national budget.”[5]

In 2004, former Election Affairs Deputy of the Guardian Council Sayed Mohammad Jahromi talked about the process of forming these offices with the newspaper Hamshahri:

“After its provincial election monitoring offices were established, the Guardian Council created a stable force of election observers that numbered about 370 to 380. This included employees, students, and teachers.”

Jahromi explained that the observers are coordinated and selected well in advance. They also receive necessary written, computerized, and verbal training in preparation for each election period.

The Guardian Council Expands

In addition to the offices in each of Iran’s 31 provinces, Guardian Council offices were expanded in the districts. There are now more than 4000 district branches tasked with organizing research networks, advocacy, and the network of election monitors.[6]

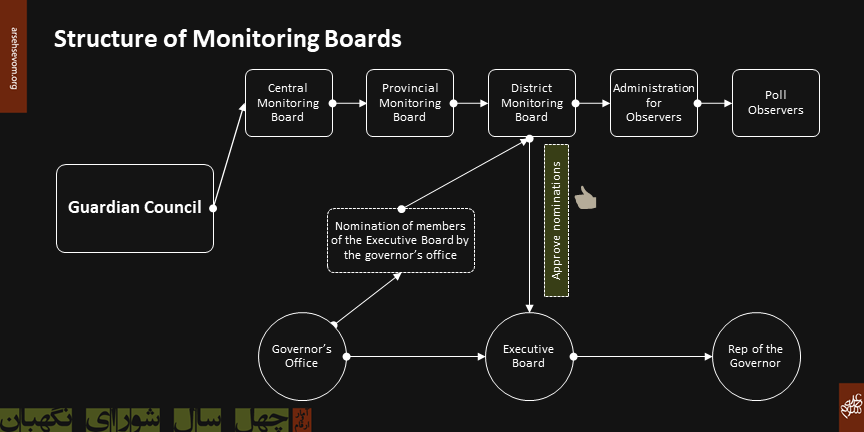

Structure of the Monitoring Boards

Structure of the Election Monitoring Boards

- The Guardian Council appoints the Central Election Monitoring Board

- Central Election Monitoring Board appoints the Provincial Monitoring Board

- The Provincial Monitoring Board appoints the District Monitoring Board

- The District Monitoring Board creates an administrative office for the Election Observers and selects Poll Observers

- The Governor’s Office sends nominations for the Executive Board to the District Monitoring Board

- The District Monitoring Board also approves nominations for the Executive Board

- A representative of the Governor sits on the Executive Board

Members of the Boards

- The Central Monitoring Board and the Assembly of Experts Elections Monitoring Board each have five members, one of whom is a member of the Guardian Council

- The Presidential Election Monitoring Board has seven members, two of whom are members of the Guardian Council

- The Central Monitoring Boards oversee Provincial Monitoring Boards: these boards have five members in each province

- Provincial Monitoring Boards select the monitoring boards at the district level: district-level boards have four members

Election Monitors

- As election day approaches, the district monitoring boards select observers for overseeing voting and the operation of the polls

- Supervisors are assigned to organize the poll observers and are introduced to the area governor

- Governors issue monitoring ID cards for the observers

The number of election monitors is different in each election. For instance, according to the operational report of the Guardian Council, there were 183,000 observers of the 2014 (11th) presidential election. There were 58,900 ballot boxes in the eleventh presidential election. On average, there were three observers for each ballet box.

More than half of the 2014 election observers had higher educational degrees from universities and seminaries. 62,000 had bachelor degrees, 7,000 had master’s degrees, 6,000 had seminary degrees, and 300 held PhDs.

Selecting Election Observers

- The 1st note of article 11 of the Parliamentary Election Code states that election observers can be hired from a pool of government employees or government associated organizations

- The Guardian Council has offices in every province and can select applicants to work as election observers

Forming the Central Election Monitoring Board

- After the announcement of elections and before the candidates register, the Central Election Monitoring Board is formed by the Guardian Council

- Article 4 of the Presidential Election Monitoring Code of 1982, stipulates that at the first meeting of the Central Election Monitoring Board, a president, vice president, secretary, spokesperson, and two clerks are elected from among the members

- The president of the Central Election Monitoring Board must be a member of the Guardian Council

- A quorum of five members is required for meetings and decisions can be made with a minimum of four votes

Function and Authorities of Election Monitoring Board (Guardian Council)

According to article 99 of the constitution, the Guardian Council is authorized to monitor the elections of the Assembly of Experts, president, and parliament. In addition, it is given the authority to refer referenda to the public. The scope of its monitoring is defined in the electoral laws. Currently, there are four separate laws covering:

- Parliamentary Elections

- Presidential Elections

- Assembly of Experts’ Elections

- City Council Elections

The duties and authorities of monitoring boards vary depending on the type of election.

Structure of the Monitoring Board for Elections of Islamic Republic of Iran

The Central Monitoring Board and its subsidiaries are responsible for reviewing the competencies, although, the Guardian Council ultimately says the final word.

Parliamentary Elections: Executive Election Board

Article 32 of Parliamentary Election Code gives the Provincial Monitoring Boards (Guardian Council-administered) authority to vet the trustees nominated by governors for the Executive Election Board (government-administered).

Criteria for the trustees is defined in Article 32 of Parliamentary Election Code. The criteria are the same for trustees as for candidates in the elections. Both must have the following characteristics:

- Faith in Islam, unless they are nominated for the seats allotted to religious minorities

- Commitment to the constitution

- Good reputation

- Literacy

- No affiliation with Shah’s or any opposition group

Responsibilities of the Executive Election Board

With oversight from the PMB, EEBs review the capabilities of registered candidates. In accordance with the latest amendments to article 28 of the Parliamentary Election Code, the candidates must meet several requirements. The simplest and most concrete requirements are used to prove the person is who they say they are. Other requirements are up for debate and can be interpreted differently by different reviewers. There has often been a disagreement between the executive and supervisory boards about what constitutes a “good Muslim,” or “loyal.” The requirements to register as a candidate include:

- A valid identity card, education diploma, proof of address, and listing of occupation

- Military service

- Iranian citizenship

- Proof of health

- Observant Muslim who performs Islamic rituals such as prayer and fasting

- Loyalty to the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, its ideology, and its political and international stances

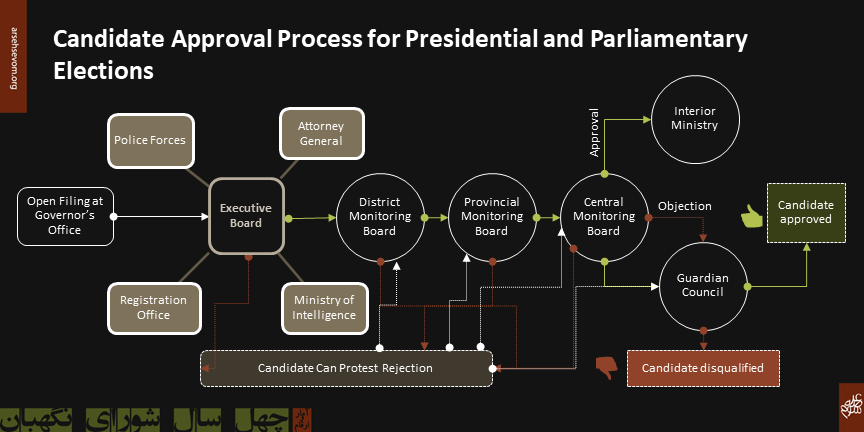

The Candidate Approval Process

The decision-making process is multi-level. From the time a candidate files until the time they are vetted and approved, there are five boards reviewing their candidacy.

- A potential candidate files their intent to run for office at the Governor’s Office

- The filing is first reviewed by the Executive Board

- If approved, it’s passed on to the District Monitoring Board, then the Provincial Monitoring Board, then the Central Monitoring Board

- The Central Monitoring Board sends approved candidates to both the Interior Ministry and the Guardian Council. The Guardian Council makes the final decision and then makes the announcements

What Happens If a Candidate Is Rejected?

The approval process is hierarchical.

- At each step of the way, a candidate can be rejected

- A candidate who is rejected can appeal their rejection every step of the way, with each subsequent board

- If the appeal reaches the Guardian Council, they make the final decision

- The decision of the Guardian Council cannot be appealed

- The Guardian Council can revoke approval for a candidate up until the day before the elections.

In 2016, the Guardian Council went beyond its mandate by reversing a candidate’s approval after she had one the election. The reason the Guardian Council gave for rejecting Minoo Khaleqi’s qualification, was that a photo had been discovered of her holding hands with a man.

Validating Parliamentary Elections

On election day, monitoring boards observe all aspects of the elections. The monitoring boards in each of the constituencies assign observers according to the proportion of the members of the executive boards for each polling station. These observers are present in the polling stations prior to opening until the end of the counting process.

On voting day the ballots of each center are stamped by the monitoring board. Ballots without stamps are considered invalid. To prevent fraud, the stamps of the Guardian Council have serial numbers that are coded in at the Guardian Council Election Headquarters. If the tallied ballots are without codes and stamps, they are considered invalid.

There are also itinerant observers who act as liaisons to the monitoring boards and observers of voting centers.

The election monitoring boards are responsible for submitting reports to the Guardian Council verifying the accuracy of the elections. According to article 70 of the Parliamentary Election Code, after reviewing reports and complaints, election boards can invalidate votes that do not change the results of the election. Otherwise, the Guardian Council is the primary decision-maker. Invalidation of elections can be done by an absolute majority votes of the Guardian Council’s members.

After counting votes, results are sent to the monitoring boards. At this stage the Guardian Council performs its final role in the electoral process, approving or rejecting the election results.

Validating Presidential Elections

In the case of presidential elections, the monitoring boards coordinate the process of holding presidential elections, as well as monitor the campaigns, the voting, and the counting of votes. Moreover, the monitoring boards review and verify the qualifications of the election implementing boards.

The Guardian Council has sole responsibility for vetting presidential candidates. This is stipulated by articles 56 and 57 of the Presidential Election Code.

According to article 79 of the Presidential Election Code, the Guardian Council has approximately 10 days after the announcement of the results to make its definitive ruling on the elections.

Complaints can be reviewed from the date of the final announcement of qualified candidates until two days after election day. Implementing boards should review complaints within 24 hours in the presence of the Guardian Council’s observers and submit the result of the review to the Ministry of Interior Affairs.

According to article 82 of the law, if the executive board determines that the election process was out of the ordinary and not done properly in one or more polling stations, they can invalidate the results of those stations once the Guardian Council confirms their findings.

The Role of the Monitoring Boards for Elections of Assembly of Experts

The process of vetting candidates and monitoring elections of the Assembly of Experts is similar to the process outlined for presidential candidates.

The elections of the Assembly of Experts are now scheduled to be held simultaneously with parliamentary elections. The Election Monitoring Boards of the Guardian Council have the responsibility for observing the election process.

Vetting, Surveillance, and Corruption

The (Dis)Qualification of the Candidates

Election Code outlines different procedures for nomination and reviewing qualifications in the three elections.

Who Can Run for Parliamentary Office?

Mashallah Heidari Moqadam, a former representative of Selseleh and Dolfan in the third parliament, has stated the has been consistently barred from running for office. The reason given for his disqualification is generally non-commitment to Islam and the guardianship of the Islamic jurist (Velayat-e-Faqih. He has repeatedly requested details, but none are forthcoming. [7]

According to article 48 of the Parliamentary Election Code, candidates need to be vetted by the following organizations:

- Ministry of Intelligence

- National Security of Iran

- Attorney General Office

- Civil and Personal Status Registration Authority of Iran

- Bureau of Identification Authority plus a query to Interpol

In addition, the Research Center of the Guardian Council collects personal information about potential candidates via their neighbors, colleagues and managers, members of their local mosque, and the local members of the Basij. Often the people contacted to provide information are unaware of the reason and the organization behind the collection.

If candidates pass each of these vetting procedures, the boards must still be convinced they are loyal to the Supreme Leader. Section 4 of article 28 of Parliamentary Election Code states that the candidates can be dismissed without sufficient proof of loyalty. Specifically, this article states that candidates must express loyalty to the constitution and the principle of the guardianship of the Islamic jurist.

All this proof of loyalty takes up a lot of paper. At least 40 pages of information about every potential candidate are kept on file. Currently, the Guardian Council Documentation Center has almost 34,000 files on all the people it vets.

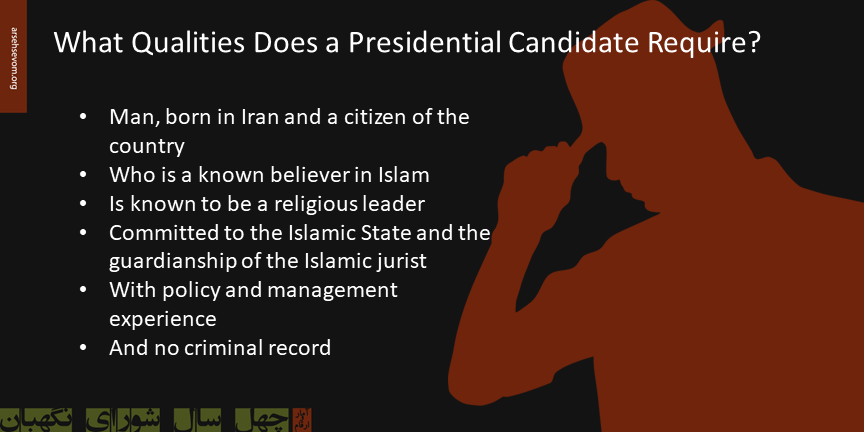

Who Can Run for President?

Are you a…

- Man, born in Iran and a citizen of the country

- Who is a known believer in Islam

- Is known to be a religious leader

- Committed to the Islamic State and the guardianship of the Islamic jurist

- With policy and management experience

- And no criminal record?

If all these things are true, you might be Iran’s next president.

The need to be a man was not always explicitly stated, yet it became increasingly obvious that no woman could make it through the qualification process.[8]

Who Can Run for Assembly of Experts?

Imagine having the power to dismiss or appoint the Supreme Leader? That’s the power the Assembly of Experts has. Here’s the catch: after being vetted by the Guardian Council and elected to a position, members of the Assembly of Experts must then be approved by the Supreme Leader.

There’s a circle of power if ever we heard of one.

Candidates for the Assembly of Experts must be jurists or Islamic scholars (مجتهد). They must have a depth of knowledge about matters of Islamic law.

Some of the less well-known or less favored candidates are required to take an entry exam administered by the Guardian Council to prove their knowledge.

The entry exam contains both a written and oral section. Passing the exam is no guarantee of qualification to be a candidate.

Details of who can run and how the elections for the Assembly of Experts are conducted are covered by Election Code of Assembly of Experts, Implementing Regulation of Assembly of Experts Elections, and Regulation of Monitoring of Assembly of Experts Elections.

Corruption in the Process

It’s not just potential candidates who find themselves under surveillance by the Guardian Council. Contenders for the election monitoring boards, elected politicians, and political activists are all under the watchful eye of Iran’s most powerful branch of government.

The Guardian Council updates the information of the representatives, political activists, and potential candidates throughout the year. Since 2007, everything has been stored in a computerized network called Bar Khat. The database was shared with provincial offices in 2010.

In the end, how is the final decision made? With all these vague requirements and all this power in the hands of investigators, the vetting process is rife with opportunities for corruption.

Parliamentarian Mahmoud Sadeghi publicly discussed corruption in the candidate vetting process. He stated that he was approached by brokers who claimed to have influence over the Guardian Council decisions. The Guardian Council refused to investigate because the claim was not documented. Sadeghi argued that there were plenty of witnesses, but they did not feel safe coming forward to testify. He made this public in a July 2018 tweet:

Parliamentarian Mahmoud Sadeghi publicly discussed corruption in the candidate vetting process. He stated that he was approached by brokers who claimed to have influence over the Guardian Council decisions. The Guardian Council refused to investigate because the claim was not documented. Sadeghi argued that there were plenty of witnesses, but they did not feel safe coming forward to testify. He made this public in a July 2018 tweet:

“Does Ayatollah Jannati [chair of both the Guardian Council and the Assembly of Experts] know of the financial corruption in the institutions they themselves run?

“If people felt secure, many would testify about what has been asked of them by the affiliates of the election monitoring boards during the vetting process.”[9]

On February 8, 2019, Mahmoud Sadeghi was tweeting again about corruption in the candidate vetting process.

“After the arrest of 12 people on suspicion of corruption in the vetting process, in a letter to the Secretary of the Guardian Council, I called for a comprehensive review of the matter. In this letter, I suggested that an expert panel be appointed to further elaborate, refine, and clarify the processes of qualification.”[10]

Mahmoud Sadeghi has been disqualified as a candidate in upcoming elections.

Attorney Mohammad Tahir Kan’ani shared his story of nomination in the Assembly of Experts to Etemad Newspaper. After his candidacy for parliament was rejected, three people came to his office claiming that they could get the Guardian Council to approve his candidacy. Kan’ani:

“I asked them, how did you find me? They said we found you via your letterhead. I had written several letters on the letterhead of my office. I asked, how will my issue be solved? They replied, ‘It will cost 600 million tomans.’”[11]

In February 2020, the vetting process was once again in the news. Twelve people were arrested on charges of corruption. Mahmoud Sadeghi took his comments to Twitter:

“After the arrest of 12 people on charges of corruption, in a letter to the Secretary of the Guardian Council, I called for a comprehensive review of the matter. In this letter, I suggested that an expert panel be appointed to further elaborate, refine, and clarify the processes related to qualification.”[12]

Power over the Future of Power

The Guardian Council has grown more powerful under the rule of Ayatollah Khamenei. It is much more than the 12 members overseeing elections and legislation. It is now a major power center, with surveillance capabilities, provincial offices, and ultimate oversight over national elections.

Potential candidates and activists are being identified before they even decide they want to run in an election. Surveillance on their activities begins when they are quite young.

Reformists, as we can see in the most current election cycle, are being shut out of the electoral cycle. At least eighty currently seated reformist members of parliament have been denied candidacy by the Guardian Council.[13]

The Election Monitoring Boards designed to control elections have led to fresh opportunities for corruption. Rejected candidates have been approached by brokers claiming to wield influence over the Guardian Council decision for the right price. In February 2020, for instance, twelve people were arrested for corruption.

This is all part of the increased institutional power of the supreme leader. Ayatollah Khamenei has been consolidating institutional power since taking on the mantle of the supreme leader.

Election Monitoring Boards are one example of this power. By controlling access to the elections on the part of potential candidates and the way in which elections are run, the Guardian Council and the supreme leader control both present and future power in Iran.

Read the complete report: The Guardian Council Expands Power (pdf)

[1] «شما باید کارتان را مستحکم کنید. .. یک تشکیلات ثابت، قوی، چابک و آماده به کاری را در تمام سال داشته باشید، شما می توانید به تعداد حوزه های مهم که در کشور هستند، عناصر ثابت داشته باشید آنها را استخدام هم بکنید. باید شما بانک اطلاعاتی داشته باشید»

[2] See the GC report (FA) for more details: https://www.arsehsevom.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/shora-do-on-election-boards.pdf

[3] On July 16, 2003, Sayed Ali Akbar Tabasi the General Administrative and Financial Director of the Guardian Council discussed the cooperation of the officials of the Office of Management and Planning in the establishment of these offices. Thus making it clear that the establishment of these offices was not a secret held solely by the Guardian Council and the Supreme Leader.

[4] Nasratollah Lotfi, the former director of the Qom province Election Monitoring Board and Inspection Office, states that provincial offices of the Guardian Council were established in September 2000. That’s when the Guardian Council sought to establish an integrated organization of election observers.

The aim of establishing these offices was to organize an election monitoring process nationwide. It was especially important for their project of vetting candidates’ eligibility controlling the polling station monitors.

[5] «شورای نگهبان مذاکرات مفصّلی با مسؤولان سازمان مدیریت و برنامه ریزی در این زمینه داشت و طبق توافقی که بعد از این مذاکرات حاصل شد فعلاً با 384 پست برای شورای نگهبان در تهران و دفاتر استانها و شهرستانها موافقت شده است. و برای حقوق و هزینه های آنها در سراسر کشور نیز بودجه پیش بینی و تصویب شده است. »

[6] The report on Performance of the Guardian Council, Chapter two

[7] For more information:

از ازدحام رد صلاحیتشدگان در مسجد سید عزیزالله تهران تا درخواست ۶۰۰ میلیون تومانی برای تایید صلاحیت

[8] Women Candidates:

قاضی فرشته. “انتخابات ریاستجمهوری؛ زنان ایرانی که ثبت نام کردند.” BBC News فارسی. BBC, April 15, 2017. https://www.bbc.com/persian/iran-features-39610887.

Guardian Council criteria and necessary conditions for determining the political, religious, leadership and other characteristics of successful candidates

[9] آیا آیت الله جنتی اطلاع دارند که فساد مالی در نهاد تحت مدیریت خودشان هم رخنه کرده است؟

اگر به افراد تأمین داده شود بسیاری حاضرند شهادت بدهند در جریان بررسی صلاحیت نامزدهای مجلس از طرف برخی مرتبطین با هیأتهای نظارت برانتخابات چه درخواستهایی از آنان شده است.

https://twitter.com/mah_sadeghi/status/1015976699622776832?lang=en

[10] پیرو بازداشت ۱۲ نفر به اتهام ادعای نفوذ در فرآیند تأیید صلاحیتها، طی نامهای به دبیر شورای نگهبان خواهان رسیدگی همه جانبه به این موضوع شدم. در این نامه پیشنهاد کردم یک هیئت کارشناسی برای عارضهیابی، اصلاح و شفافسازی فرآیندهای مربوط به احراز صلاحیت ها تعیین شود.

https://twitter.com/mah_sadeghi/status/1226122378096398337

[11] Around 140,000 USD

[12] پیرو بازداشت ۱۲ نفر به اتهام ادعای نفوذ در فرآیند تأیید صلاحیتها، طی نامهای به دبیر شورای نگهبان خواهان رسیدگی همه جانبه به این موضوع شدم. در این نامه پیشنهاد کردم یک هیئت کارشناسی برای عارضهیابی، اصلاح و شفافسازی فرآیندهای مربوط به احراز صلاحیت ها تعیین شود.

https://twitter.com/mah_sadeghi/status/1226122378096398337?s=20

[13] Azizi, Arash. “Factbox: Iran’s 2020 Parliamentary Elections.” Atlantic Council, February 14, 2020. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/iransource/factbox-irans-2020-parliamentary-elections/.