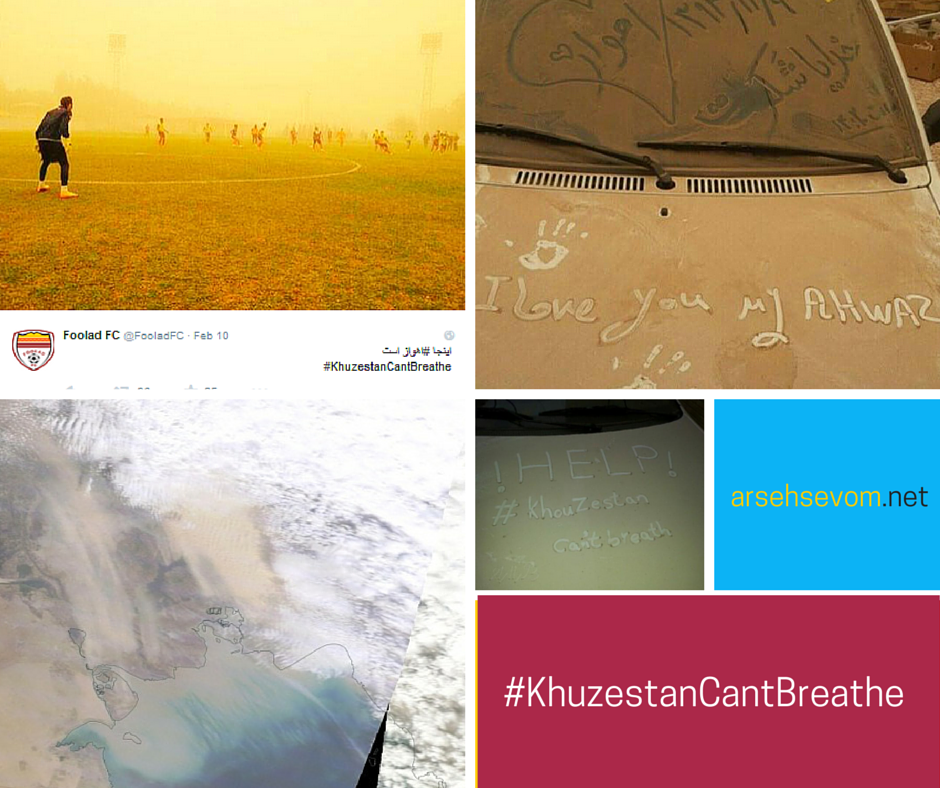

Sandstorms Suffocate Iran

February 14, 2015

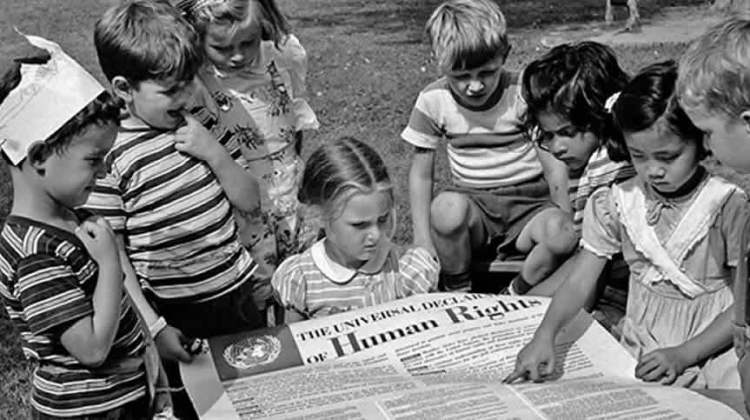

Facts About Human Rights in Iran

March 12, 2015How can human rights groups focusing on Iran learn to work together and become more professional? This article, written by Tori Egherman and originally published in Iran Human Rights Review explores possibilities for cooperation and increased professionalism among human rights organizations.

A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats: Cooperating for Change

Cooperation among human rights activists and organisations among the diaspora focusing on Iran has increased in an uneven manner over the past few decades. There are many reasons for this, including the professionalisation of human rights over the past fifteen years. “In the eighties and nineties,” Kamran Ashtary, Director of Arseh Sevom,[1] stated, “human rights activists weren’t as professional as they are now. We realised the necessity of collaboration, but we didn’t know how to do it. We were so much into all or nothing cooperation that we were not effective.” [2]

Mr Ashtary continued by pointing out that there was always cooperation on human rights issues within parties and groups with similar ideologies, but that over the past five years there has been an increase in cooperation among groups and individuals with ideological differences. The experience gained through the appointment of the Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Iran, as well as working with the appointee on reporting, has brought about a new confidence in the benefits of cooperation to achieving respect for human rights in Iran.

Despite this, activists and civil society organisations can find hundreds of reasons not to work together, from differing political views, to mistrust, to a lack of experience to the random inflated or delicate ego. “There is no one who says they don’t want collaboration,” a human rights lawyer stated in an interview.[3] “That would be taboo. After all, we are all civil society organisations trying to get along.” In many cases the habit of living in a repressive culture means trust can be difficult to build. In societies like Iran, civil society can be viewed as a threat, in conflict with authorities and the state. As a result, the muscles for cooperation and for working with allies are not exercised.

In a 2011 interview, international human rights expert, Dokhi Fassihian reported on discussions with a network of professionals from Mexican civil society organisations who were reflecting on the transition from confrontation with the state to working with it:

The issue of trust is not unique to Iran. In many societies where the way human rights activists work is primarily underground, where activists are under attack they are always in a confrontational mode. When I spoke to Mexican organizations about this in Mexico City, they discussed the fact that not being in a confrontational mode, accepting or talking to governments as an ally, as a partner seems wrong to them. Some of them still struggle with that from when they had a dictatorial government and some still function as confrontational.[4]

When trying to influence international bodies and make changes in policy, working together is absolutely necessary. What can be done in collaboration with others is much greater than what can be done by lone individuals or small groups.

Whether they represent the European Union, the governments of the ‘Global South’, or the United Nations, officials and their staff need to have confidence in the claims being made and the people and organisations making them. This is made easier when they are approached by coalitions in addition to individuals and individual organisations. A coalition can demonstrate the strength and depth needed to back up claims. Coalitions help bring attention to a cause. Influencers and decision makers have limited time. By approaching them as a group, the chances of being heard increase. In the case of the United Nations, it is important to remember that individuals represent countries: influencing them means influencing the decision makers of an entire country. This is more effectively done by groups working together than by an individual voice.

The appointment of the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights on Iran is an example of what can be done when organisations and individuals concerned with the same issue from many different angles work together.[5] After the flawed 2009 presidential elections in Iran, concern about human rights abuses was at a high. Executions were proceeding at a fast pace. Mass arrests and appalling prison conditions were receiving more attention than ever before. Widespread use of social media meant that conditions in Iran were reaching a wider audience inside and outside the country. The situation demanded response. Human rights groups, defenders and civil society organisations representing many different interests worked together to get the UN Human Rights Council to act.

Statements, individual meetings, opinion pieces, letters and the lobbying of representatives and officials were all part of a strategy to sway the council to vote in favour of the appointment of a Special Rapporteur. Dokhi Fassihian, then director of the Democracy Coalition Project, was actively involved in the process of working for the appointment. She stated:

These rapporteurs, specifically country rapporteurs, don’t come easy. It takes an enormous amount of political effort, wil, and capital to appoint one of these individuals to report regularly on a situation. We don’t have that many country rapporteurs, precisely because it’s quite difficult to get them appointed.

For its success, it was critical for the coalition to convince undecided countries such as Brazil to vote in favour of the appointment. In the particular instance of Brazil, a group of 180 Iranian women’s rights activists wrote a personal letter to its president, Dilma Rouseff. She had been imprisoned herself for her opposition to dictatorship. The women wrote:

You know through experience that in order to legitimize the suppression of people, activists, and people’s movements, those in power may accuse and convict people on fabricated charges and crimes. You, who have fought for the Brazilian people’s dignity and freedom, know that idealists are constantly accused by those in power of cooperating with foreigners or similar offenses deemed worthy of punishment. Many ethnic rights activists, journalists, labor and political activists have recently been handed heavy sentences for such alleged crimes.[6]

The proposal for the appointment of a Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Iran was brought to the council three times before receiving approval in March 2011.[7] Brazil was one of several swing countries to vote in favour. None of this would have been possible without the efforts of many different parties.

Three years into the maximum six-year term for the Special Rapporteur, organisations are still struggling to find ways to work together. For many, the biggest obstacle is changing course from advocating directly with the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran to communicating with international mechanisms such as the UN. A human rights lawyer (2014) interviewed commented:

There is a sort of lack of capacity around the UN and there’s also a lack of coordination. Organizations have somewhat different viewpoints and agendas but they’re all ultimately trying to work within the framework of international human rights law, so the range of what they’re asking for is not that wide necessarily. Out of conversations with these groups and attending conferences and workshops with a lot of Iranian human rights activists there just appeared to be a glaring lack of coordination for some joint actions, particularly targeted to the UN, as well as a lack of capacity and know-how by some organizations.

On an optimistic note, in early April in a meeting room at a Toronto hotel, Dr Ahmad Shaheed, the Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Iran discussed his mandate and experiences investigating human rights abuses in Iran. The room was filled with people who had been at the receiving end of state-sponsored abuse, plus journalists, activists and others interested in the topic. At one point Dr Shaheed commented on the power of the collaborative efforts undertaken by human rights organisations focusing on Iran. The help with research and translation was invaluable to him. He reminded the group that his resources are limited to himself and a part-time administrative assistant. His work, he told us, depended on help from many others.

A couple of weeks earlier there had been a vote to extend his mandate as Special Rapporteur for another year.[8] This was achieved with the work of many organisations working together to advocate for its renewal.

In conclusion, to quote the words of a human rights activist stated in an interview, “When I used to play in bands, we believed that if our scene was successful, our band would be successful. You know the saying ‘A rising tide lifts all boats.’ That’s the attitude I’d like to see in the human rights community.”[9]

[1] The content of this article is based on research for Arseh Sevom’s project, Civil Society Cookbook. Some of those interviewed asked to remain anonymous.

[2] Interview with Kamran Ashtary, 2014. Changes in human rights advocacy in the Iranian community. Interviewed by Tori Egherman. Amsterdam.

[3] Interview with human rights lawyer. 2014. Collaborative work with civil society groups. Interviewed by Tori Egherman and Rumiyana Panayotava, Skype call.

[4] Interview with Dokhi Fassihian. 2011. Working with the United Nations. Interviewed by Tori Egherman. Skype call.

[5] Arseh Sevom, Human Rights Council Appoints Special Rapporteur for Iran. March 2011, https://www.arsehsevom.org/en/2011/03/human-rights-council-appoints-special-rapporteur-for-iran/

[6] Text of the letter can be found at the website for the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. ‘180 Activists Ask of Brazil’s President: Show The World You Object to Human Rights Violations in Iran’ http://www.iranhumanrights.org/2011/03/180-activists-brazil/

[7] Arseh Sevom, Human Rights Council Appoints Special Rapporteur for Iran. March 2011, https://www.arsehsevom.org/en/2011/03/human-rights-council-appoints-special-rapporteur-for-iran/

[8] The vote to extend the mandate of the Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Iran was passed on March 28, 2014 with 21 votes in favor, 16 abstentions, and 9 opposed. The New York Times published a graphic image of the vote that can be seen here http://graphics8.nytimes.com/packages/html/world/voteiran.pdf, and wrote about it here: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/29/world/middleeast/United-Nations-Iran.html

[9] Interview with human rights activist. 2014. Collaborative work with civil society groups. Interviewed by Tori Egherman and Rumiyana Panayotava, Skype call.