At the end of 2012, an independent evaluator made an extensive review of our practices and accomplishments over its first three years of operation. The evaluator spoke to a number of people affected by the organization’s work. He wrote:

Arseh Sevom was several times referred to as being and creating “a living exercise in democracy.” This is a compliment that simultaneously includes a task and challenge for the future!

What do we mean by civil society?

When Arseh Sevom got together to hammer out our vision and mission, we took it really seriously. We read up on civil society and the varying definitions. We expressed concern that by some definitions, civil society could be construed as anti-democratic and oppressive. We searched for a meaning we could agree on and that expressed our values.

In the end, we adopted John Samuel’s characterization of civil society as informal, semiformal, or formal organizations that protect, promote, and facilitate principles and practices of democracy, participation, pluralism, rights, equity, justice and peace among people locally, nationally, and internationally.

By adopting this definition, we aim to work with groups that recognize the rights of others and encourage practices of inclusion. The protection and preservation of minorities among Iranians is of paramount concern for us.

Arseh Sevom works to create tools, resources, and opportunities for learning and collaboration that promote a capable, vibrant, and pluralistic civil society transnationally, including inside Iran, in the diaspora, and among related language and cultural communities.

OUR VISION

We envision a strengthened civil society in Iran and among related communities transnationally that is capable, pluralistic, participatory, and effective at achieving its objectives.

VALUES

Human dignity through actions that are anti-racist and challenge the societal norms that marginalize people because of who they are.

Freedom of expression, religion, and assembly.

Democracy and the protection of rights and minority populations through democratic practices.

Human rights expressed through a rights-based approach to problem solving.

Arseh Sevom is funded in part by our readers and individual donors. Thank you to all of you.

Projects

2021

Project Bani Adam

Bani Adam is the Persian term for human beings. Literally, it means “children of Adam.” Arseh Sevom named this project for the poem by Saadi which reminds us that we share our humanity with each other. We are not alone. Our destiny is entwined and love and shared responsibility are absolutely necessary for us to ensure the future. Saadi tells us that discrimination and hate hurt the whole of society.

Bani Adam is the Persian term for human beings. Literally, it means “children of Adam.” Arseh Sevom named this project for the poem by Saadi which reminds us that we share our humanity with each other. We are not alone. Our destiny is entwined and love and shared responsibility are absolutely necessary for us to ensure the future. Saadi tells us that discrimination and hate hurt the whole of society.

We encourage people to speak out against hate speech and take more responsibility for ensuring that the rights of systematically oppressed communities are guaranteed. Arseh Sevom’s Executive Director Kamran Ashtary says:

“If we’ve learned anything the past few decades it’s this: our fates and our lives are interconnected. Those of us living outside of Iran have had to find ways to live in new societies and new cultures. Many of us have faced discrimination and hate because we are outsiders. At the same time, we have contributed to hate and discrimination through our own language and actions. We are not only victims. We are not only perpetrators. There are many ways we interact in society.

For me, personally, seeing the growth in Holocaust denial being spread in the Persian community and the casual ways we express racism has been especially eye-opening and painful. I really believe we can change. I believe that we can be better in our language and our actions. But we won’t unless we work at it. That’s why Arseh Sevom is founding this new project.”

We know that looking at the ways we ourselves contribute to discrimination and hate can be hard. We are determined to become comfortable with discomfort.

Project Bani Adam embraces these values:

- Human dignity through dismantling racism and xenophobia

- Democracy: particularly, the protection of rights and minority populations through democratic practices

- Human rights

2015-2020

Power in Iran

From 2015-2020, Arseh Sevom work focused on power in Iran. We researched, documented, and created content related to the power structure and how it works. Even if by some miracle, Iran were transformed into a real democracy tomorrow, these power structures would continue. They impact every aspect of society.

Many may think that power in Iran is a simple thing. We all know the basic structure: Supreme Leader, judiciary, parliament, Intelligence, Revolutionary Guards, and the military. Simple.

That structure is the tip of the iceberg.

Did you know that the Guardian Council has its own intelligence service and armed militia? Did you know that a large portion of Iran’s national budget is divided among a small number of Islamic charities that have no obligation of transparency?

Family is important in Iran. It’s a tie that goes back hundreds, if not thousands of years. People often talk of the seven families, which perhaps have roots all the way back to the period of Cyrus the Great. It’s a badge of honor to many, an acknowledgment of respect.

The flipside of the respect for family is outsized nepotism in both the private and the public sectors. The parliament itself has been referred to as a “brother-in-law-ocracy.” Family ties control access to power and wealth. They also can land you in prison, as many in Iran know all too well.

|

|

GUARDIAN COUNCIL: OBSTACLES TO DEMOCRACY

|

Dar Sahn and Lead Local

In English, Dar Sahn means The Floor, as in who has the floor? In other words, the floor refers to the right and opportunity to speak up whether at a meeting of peers or in parliament or wherever groups gather.

Dar Sahn has many aspects all focused on bringing more accountability to national and local government. Citizen journalists cover issues important in their local communities. Journalists profile members of parliament. Researchers and educators provide information for engaging with local government. Educators create content to inform people about how to get involved with local councils as candidates and as community representatives.

Dar Sahn isn’t just about great content, it’s about creating a culture of reporting that is fair and factual. And people are taking notice. The practices of our journalists are being shared and discussed along with the content they create.

The project is also about taking actions that create more representation and attention for the needs of communities.

Over one million people have been reached through our website and social media. Toolkits about becoming involved with civil society and local councils were shared, viewed, and downloaded more than the 500,000 times.

“For the first time since the revolution, there were no representatives of the Revolutionary Guards or Militia elected to Tehran’s city council.”

Project Overview

Dar Sahn and Lead Local

More than 120,000 city council members are elected in 10,000 cities, townships, and villages all over Iran each election cycle. Their influence is often underrated, yet they have considerable influence over the lives and well-being of millions in Iran.

When moderate voters stayed away from the polls in the early 2000s, the councils were taken over by hardline politicians, which led to a resurgence of hardline governance in Iran and the rise of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Dar Sahn and Lead Local focused specifically on engaging with important issues at the local level with a network of volunteers, citizen journalists, and activists. The project was divided into four parts:

Local Issues

Create space for discussion of issues that are important to local communities

Parliament Profiling

Profile individual members of parliament, committees, and factions based on adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and influence on local funding

Local Watch

Report on and monitor activities of local governments as well as the supreme councils of the provinces

Local Engagement

Tools to help civil society and new leaders engage with local government

For more information: http://www.darsahn.org/

Rayeman

Rayeman (My Vote) is a partnership with Amsterdam’s KiesKompas (Electoral Compass). It’s designed to gauge the attitudes of people in Iran to a number of local issues.

We identified over 500 issues that were occupying people all over Iran. Our focus was on localities. Those issues included everything from access to safe pedestrian walkways to child marriage to lack of employment opportunities. People expressed concern about water, pollution, and education, as well as corruption and construction practices.

Together with KiesKompas, Arseh Sevom created a survey that attracted several hundred thousand visitors. Their response to the survey allowed them to have a better understanding of their political personality. Were they egalitarians? Lavish conservatives? Skeptical optimists?

Follow the Money

The results of devastating sanctions show up in all aspects of society. The shopkeeper blames sanctions for the lack of basics, the pharmacy blames sanctions for the lack of medication, the government blames sanctions for their own policy failures and the militarization of the economy. Capital has fled from the poor and middle class to the wealthy, and wealth inequality in Iran is at an all-time high.

The results of devastating sanctions show up in all aspects of society. The shopkeeper blames sanctions for the lack of basics, the pharmacy blames sanctions for the lack of medication, the government blames sanctions for their own policy failures and the militarization of the economy. Capital has fled from the poor and middle class to the wealthy, and wealth inequality in Iran is at an all-time high.

One aspect of the combination of sanctions and wealth inequality is an elite that is effectively unable to travel or to spend or invest their money elsewhere. They are creating entertainment and opportunities for themselves within the country. If all you know of Iran is what the wealthy choose to show you, you might think that glamorous young folks in impeccable clothing and makeup dancing into the night is normal. But in fact, the vast majority of Iranians are struggling to make it through the day.

On December 10, 2017, Iran’s president Rouhani presented a draft budget to the parliament’s finance committee. In a way, the presentation of the budget was a small victory for transparency. The delivery marked the first time the total year’s budget had been delivered at once. People took note. A lot of what they discovered made them angry.

The budget included increases to Islamic charities and cuts to subsidies, sparking popular protests all over the country. Yet even before the budget was presented, bus drivers, teachers, retirees, and other labor unionists had been protesting cuts to pensions and delays in payments, as well as unfair labor practices. Every day for weeks they had gathered in front of Iran’s parliament.

Arseh Sevom’s budget project, Follow the Money, untangled the process of creating the national budget and profiled five Islamic charities (bonyads).

Profiles of bonyads (fa): https://www.arsehsevom.org/category/budet-iran/gozaresh-e-bonyadha/

The Iranian national budget (fa): https://www.arsehsevom.org/budgetpage/

Hen House

When we are worried that someone might exploit or harm the resources they are trusted with, we often say that it’s like letting the fox guard the hen house. In other words, a bad idea.

When we are worried that someone might exploit or harm the resources they are trusted with, we often say that it’s like letting the fox guard the hen house. In other words, a bad idea.

Have you ever wondered who’s guarding the hen house in Iran? Arseh Sevom set out to answer that question by examining the financial holdings of key Rouhani administration cabinet ministers.

Nepotism and conflicts of interest are the norms in Iranian politics. It isn’t unusual for ministry candidates to have shares in companies that do business with the ministry or are affected by ministry regulations.

With no coherent and feasible plans to build confidence either financially or societally, those with the access and means amass more and more of the country’s resources for themselves. This includes the cabinet of the president. There are indications of corruption on the part of ministers and deputies of Rouhani’s first and second governments. For example, there is evidence that the family of the minister of industry and mining controls at least nineteen companies doing business directly with the ministry.

Private companies find that the cost of doing business is by seating members with connections to the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC) or other powerful institutions on their boards. This is not so different than the methods used to gain control of civil society organizations where independent boards were replaced with members of the IRGC and people with ties to the Supreme Leader’s office and other arms of the government.

The problem is bigger than accusations of nepotism and corruption against cabinet members. There are no anti-corruption policies. Instead, there is a lack of oversight of both civilian and public institutions that allows politicians and military personnel to hoard the country’s capital and resources for their own interests, whether military, political, religious, or personal.

Cabinet ministers blame all economic problems on the sanctions when the real problem is corruption.

Corruption democratizes oppression, making it difficult to pinpoint roadblocks to democratic change. Those who benefit from corruption work to prevent the free flow of information. Pervasive corruption is a bigger threat to better governance and respect for human rights than ideology.

Arseh Sevom has always taken the point of view that change needs to come from societies transitioning to democratic practices through acts of inclusion, critical thinking, and truthful communication. Yet corruption creates forces that circumvent all but cosmetic changes.

You can find the Hen House project here (fa):

https://www.arsehsevom.org/government-cabinet-homepage/

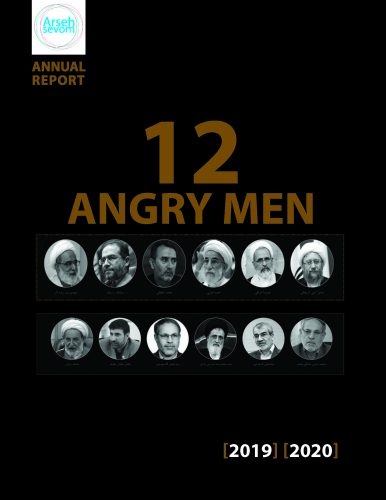

Obstacles to Democracy: The Guardian Council

Obstacles to Democracy shows an expansion of power by the Guardian Council and Iran’s Supreme Leader. The Guardian Council is not merely an institution with twelve members, it has offices all over the nation. Since 2001, it has been expanding its influence on elections through surveillance and demands for ideological conformity from candidates. In fact, in the 2020 elections, it prevented the candidacy of nearly every single reform-minded or independent candidate. This includes rejecting the candidacy of 90 sitting members of parliament, many of whom are affiliated with the reformists or independent.

Obstacles to Democracy shows an expansion of power by the Guardian Council and Iran’s Supreme Leader. The Guardian Council is not merely an institution with twelve members, it has offices all over the nation. Since 2001, it has been expanding its influence on elections through surveillance and demands for ideological conformity from candidates. In fact, in the 2020 elections, it prevented the candidacy of nearly every single reform-minded or independent candidate. This includes rejecting the candidacy of 90 sitting members of parliament, many of whom are affiliated with the reformists or independent.

So, even though there are 12 members of the Guardian Council, it now reaches into every corner of society. Since 2001, it has been expanding its influence on elections through surveillance and demands for ideological conformity from candidates. In fact, in the 2020 elections, it prevented the candidacy of nearly every single reform-minded or independent candidate. This includes rejecting the candidacy of 90 sitting members of parliament, many of whom were affiliated with the reformists or independent.

Arseh Sevom’s breakthrough report on this is a must-read for anyone who wants to know more about how power in Iran works.

Find the Persian content here: https://www.arsehsevom.org/guardian-council/

2010-2014

Civil Society How-To and Reporting

How in the world do people come together to actually form a civil society? That’s the question Arseh Sevom seeks to answer in the Civil Society How-To. We spoke to civil society activists and other experts about how civil society works. The project shares their experiences and knowledge building democratic organizations, using theater to engage communities, and generally being amazing activists working to improve their communities.

How in the world do people come together to actually form a civil society? That’s the question Arseh Sevom seeks to answer in the Civil Society How-To. We spoke to civil society activists and other experts about how civil society works. The project shares their experiences and knowledge building democratic organizations, using theater to engage communities, and generally being amazing activists working to improve their communities.

Here’s what Oxfam Novib’s executive director in the Netherlands, Farah Karimi, told us:

“You want to do something about injustice, because if you think ok, I am angry, or I am disappointed, or people are bad and that is never going to change, then that anger and disappointment can translate itself into frustration and even into hypocrisy. But I try to translate my anger into positive action. I think, what can I do about it? What can I change?”

Find more interviews, activities, and content here: http://www.civilsocietyhowto.org/

In addition to the how-to. Arseh Sevom published two civil society zines exploring topics related to movements and organizations all over the world. These zines augmented our weekly roundups on civil society, interviews, and other content. Go ahead, take a look. We have everything organized for you here: Annual Reports, Civil Society Zine, other Reports (en)

ANBI Status approved

RSIN

822076548

Contact

talktous@arsehsevom.net

Board

Arseh Sevom’s Executive Board serves as volunteers. The bylaws prohibit receiving a salary from the organization. They are reimbursed for travel and expenses made on behalf of the organization.

Supervisory board

A. Taken, President of the Board

S. Loyst, Secretary of the Board

K. Hashemi, Treasurer

Managing director: K. Ashtary

Policies

Download a summary of our policies: AS: Policy Overview

Our complete policies are available upon request: talktous@arsehsevom.net